by Karthika Jayakumar and Sivakami

Recent events have coerced Keralites to reflect on the façade of progressiveness borne so proudly by the State. Lauded for its development experience, the continued prevalence of crimes like dowry deaths are reminders of the skewed power structures and deep-rooted patriarchy that has a stronghold here. The tipping point was on June 21, when 24-year-old Vismaya V Nair took her life a few days after sharing photos and WhatsApp chats with her family about being subjected to abuse at the hands of her husband, over the latter’s distaste regarding the ‘insufficient’ dowry that was given to him. This was closely followed by the death of two more women for similar reasons.

In the multitude of heated debates and arguments that followed the case, on social media and mainstream news channels alike, caste as a vantage point was conveniently obfuscated. Victim blaming and gaslighting were the dominant tones that surrounded the outrage against the case which revealed our internalized misogyny and prejudices when it comes to issues of dowry and domestic violence.

Maintaining caste hierarchy through dowry exchange

In the ensuing conversations, victim-blaming was a dominant tendency. Gaslighting the victim is not only patronizing but also re-affirms the age-old trope of declaring the victim to be mentally unsound when she is driven to suicide. This doesn’t hold the patriarchal husband figure (the perpetrator) accountable. His sense of entitlement and impunity are fuelled by the upper-caste Hindu family structure. Conventional Hindu marriages are cis-het, caste endogamous unions that don’t have much to do with love. Monopoly over property ownership and lineage concerns are at the core of such matchmaking and dowry is rooted in this political economy of marriage. Caste associations often enforce property agreements through endogamy while also popularizing a ‘sacramental’ union. Such dowry exchange also includes assessing masculine and feminine attributes along with evaluating the wealth status of prospective partners.

Furthermore, capitalism and consumerism have transformed social identities turning dowry into an institution that affirms the value of a man. For socially vulnerable families, dowry is the price that has to be paid for aspiring the markers of respectability in endogamy, stable marriage and sexual discipline. The more the dowry, higher is the ‘esteem’ associated with the particular caste group. As awareness and talks about dowry have found some root in mainstream dialogue, the self-proclaimed ‘progressives’ have found a way to disguise dowry as hidden transferences or ‘gifts’, or even as a symbol of parental love. However, the nature of transference doesn’t hide its underlying purpose.

Institutionally, the patriarchal authority has also been transferred from the previous framework of Jati and agrarian relations to modern conjugal institutions which enforce strict endogamy, monogamy and restrictions over divorce, separation or remarriage. Through this, men acquire power over women as principal guardians, ‘legitimate’ custodians of female sexuality and ‘protectors’ of their property. Thus women’s sexuality and agency undergo policing as they become a medium through which prestige and wealth are transferred between families.

The centrality of marriage to the feminine self

Marriage controls a woman’s professional, social and economic choices as her roles are exclusively defined within the context of family life. Single, divorced or widowed women are socially ostracised in subtle and overt ways as their legitimacy is denied when they exist outside the frameworks of conjugality and caste.

Since the Brahmanical diktats of Manusmriti describe the ideal wife as one whose dharma is to live in servitude of her husband, the onus and therefore the pressure remains on the woman to uphold the ‘honour’ of her community.

Vismaya’s father-in-law even admits that despite her wish to return home, they paid no heed as ‘young girls nowadays created a big deal out of things’. She was also pacified to stay put in her marriage, with due assistance from local members from the Nair Service Society (NSS). Such toxic caste organizations and unruly Hindu mobs function to further enforce caste norms through moral policing. Marriages between Hindu women and Muslim men also fall prey to such vigilantism by getting labelled as ‘love jihad’ (also under the recent anti-conversion laws), a propaganda to criminalise Muslim men by the State.

A divorced daughter is ‘better than a dead daughter’ was one of the many self-affirming tropes that surfaced. Although it is important to normalise divorce in a society where it is considered taboo, by making the comparison of divorce being the better outcome than death, there is active invisibilization of the evils of caste endogamy and abuse even implies that besides being dead, getting divorced is the next best acceptable option for a woman.

When Vismaya became the face of the oppression women face in marriages, the chairperson of Kerala women’s commission, MC Josephine’s apathy became the face of the society that nurtures such violence. The internalized misogyny and social privileges of women in power only serve to perpetuate patriarchal violence further, rather than create a rupture in the status quo. Those who invalidate a victim’s suffering reaffirm their worst nightmare of being invisibilized or disbelieved when they speak up. The misguided social outrage against such deaths is the most telling way in which the community-at-large perpetuates them.

Often the trauma response of the victims may seem like internalized misogyny, when they cannot bring themselves to register a complaint as notions of privacy and ‘sanctity of the family’ are often evoked to minimize legal interventions in marriage. These fail to challenge structural and ideological conditions that provoke domestic violence and dowry deaths. Furthermore, children who grow up in such abusive households grapple with the collateral damage inflicted on them by their families.

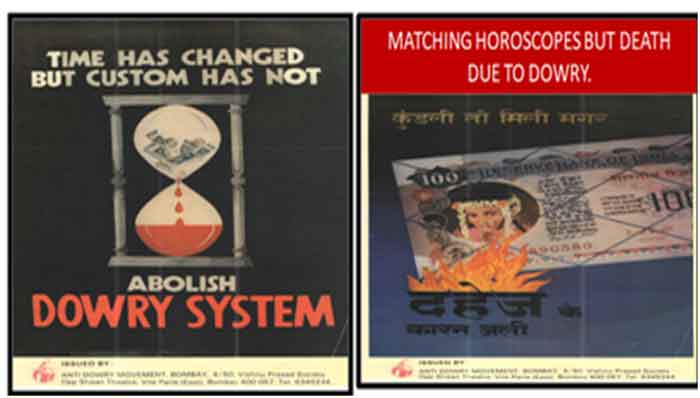

The well-established inferiority of women in marital relations has normalized emotional and physical violence to the extent that only the most gruesome of abuse or death is deemed worthy of our attention. Despite the enactment of the Hindu Code Bills drafted by Dr BR Ambedkar, the Dowry Prohibition Act (1961) and dowry deaths being recognised as an offence in 1986 by the virtue of section 304-B, the law is largely symbolic and has failed to challenge the institution of caste-based marriages. While the images of the dowry problem range from conspicuous consumption and expensive weddings to extortion and domestic violence, the state and legal response have operated to maintain the gender and family ideology in India.

To envision a positive future would be to abolish hierarchical structures of caste that dictate oppressive patriarchal norms in our society. It is also imperative that we decenter heteronormative conceptualisation of family as an institution and make space for non-normative unions to thrive and challenge this hegemony.

Karthika Jayakumar and Sivakami Prasanna are graduates from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Tuljapur, Maharashtra