Recently I watched a film with the title “ Project Marathwada”. The story is about an old farmer from Nandurbar , a small town in Maharashtra. He wants to meet the Chief Minister. His son has recently committed suicide due to mounting debt and so have so many other farmers in the area. He is unable to meet the Chief Minister as he is a commoner and has no appointment. He goes into a depression and attempts to commit suicide. The police arrest him for attempting to commit suicide. He then meets with a group of students who are researching and making a short film on the framers suicides. They figure out that he is in a mentally disturbed state and that he needs counselling and support. And there lies the tension.

The prevalence of suicides has been increasing in recent years. The number of persons who attempt to die by suicide is 25 times that of the number of those who die by suicide every year. Indian Government passed the Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 in the middle of 2018. Section 115 of the act decriminalized the attempt to die by suicide, thereby reducing further stress on the victim. This has legal implications with regard to abetment laws of Sections 109, 116, 306, and 309 of Indian Penal Code.

It can be argued that that the Victorian era law criminalising attempted suicide is the contribution of the colonial past. And they would not be wrong. A lot of our laws are a vestige of the world view that existed in the 19th century England. The concept of mental illness was little understood or explored then. Human conduct was either all black or all white.

Today of course there is a lot more that known about suicide. There are many factors that can influence a person’s decision to commit suicide. The most common one though is severe depression. Depression can make people feel great emotional pain and loss of hope. This makes them unable to see another way to relieve the pain other than ending their own life. Most people impulsively decide to attempt suicide shortly before doing so. Planned suicides are relatively uncommon

Knowledge about the triggers of suicide and its causes is mostly confined to the academic community or mental wellness campaigners. It hasn’t percolated much more down. A person rushed to a hospital after an attempted suicide may find themselves mixed up in a medico legal case. This is separate from the social stigma they will face upon discharge.

Suicides in India often come to light when a celebrity commits suicide or attempts one . The coverage then raises more sound than substance. Take for example the suicide of the actor Sushant Singh Sharma who hung himself last year in his home. The intial media conversations focused on suicide prevention a bit. Soon enough though, the conversation shifted to his possible involvement with drugs and drug dealers. Now films are being made on the late actor’s life but how many will focus on suicide prevention issues ?

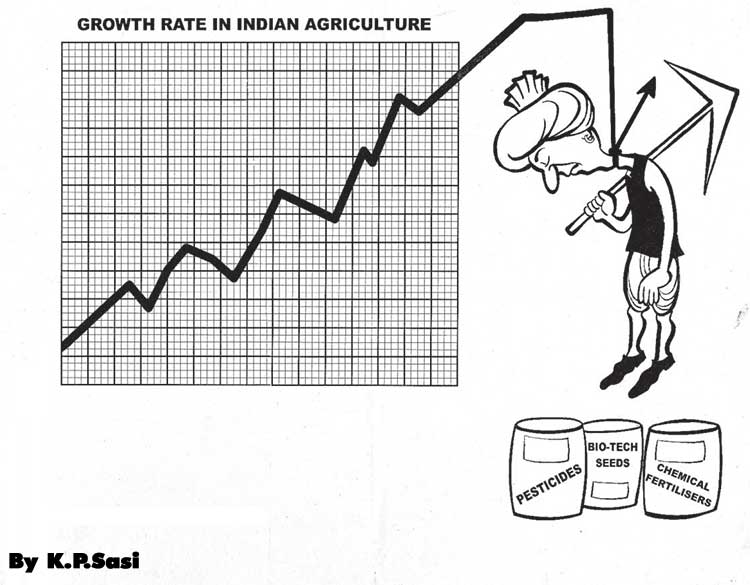

Farmers suicides also have been getting some traction, though not directly connected to suicides. The focus has been on the phenomenon of rural indebtedness due to many reasons – some of which highlighted in Project Marathwada. Needless to say these issues need addressing too. In fact they actually throw light on the complex causality of suicides which mental health professionals don’t have the bandwidth to address.

Can suicides be prevented ? The answer is again complex. The immediate remedial measure is usually having the suicidal person talk to some one; ideally a friend or close confidant. This is not easily found in the atomised society that we live in. The challenge was magnified during the Covid lockdowns as people remained confined to their homes and social contact disappeared. Many sprung to help by offering free counselling as well as setting up suicide helplines. As was to be expected, the system limped. Helplines often went unanswered or worked for a certain number of hours every day. India has a shortage of trained mental health professionals and even para professionals. In their absence enthusiastic volunteers were often given a crash course and put on the job. Often they were not upto it.

Helplines and timely counselling can bring a person back from the brink. Regular therapy and counselling can treat, if not cure depression and other mental illnesses if the cause is purely clinical. But often people dial into these helplines or seek counselling at a fairly late stage when someone intervenes on their behalf. There is no telling as to how many people have no one to intercde on their behalf and die unsung. As usual, in India the numbers are likely to be much higher than in urban India.

Are barefoot counsellors the answer ? Can they be the 1st responders in times of crisis such as this ? In some states like Tamil Nadu and West Bengal , they have proved to be useful. In the Tamil Nadu model, the women counsellors after initial training start connecting with the community but they also remain connected with experts through technology like Skype. This enables them to continuously keep upgrading their skills, as well as ask for and receive feedback. Although counsellors and therapists may not be able to help with the larger causes that cause depression, they can surely help build community resilience and better coping abilities and help prevent suicides among those who have access to no other tools.