Abstract

The stability of the Earth’s ecosystems, and hence the future of the human species, depends on people recognizing and responding to multiple, cascading social and ecological crises that can easily overwhelm our imaginations. We need to cultivate restless and relentless minds to deal with unprecedented analytical questions and moral challenges if we are to go beyond the failed approaches of our current politics. This requires a sense of history deeper than we typically see in current debates. Since the advent of agriculture more than 10,000 years ago, humans have been a “species out of context.” That awareness will help us formulate “questions that go beyond the available answers,” which are necessary if we are to fashion effective responses to the crises. In this presentation, Robert Jensen highlights a half-century of work by one of his elders, Wes Jackson of The Land Institute in Kansas (USA), to suggest approaches to analyzing the threats at this moment in history. This lecture draws on Jensen’s 2021 book, The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson: Searching for Sustainability (University Press of Kansas) and a forthcoming book co-written with Jackson.

Introduction: Restless and Relentless

I have lived an extraordinary life. I don’t mean that, as an individual, my life has been anything special. I’m pretty ordinary. In fact, most days I have to work hard to get to ordinary.

But I was born in 1958 in the United States, an extraordinary time and place. That’s not because America is so great—“extraordinary” in this case is a description not a value judgment—but because it is so wealthy and expansive. I was born in the richest society in the history of the world, at a time when people—not only in the United States but all around the world—expected endless economic expansion. In my lifetime, people in industrial societies came to see affluence as normal, and most people who were excluded from that affluence aspired to it.

This has been a period of human history marked by an extraordinary level of more—lots more people and lots more stuff made possible by lots more energy. Although the wealth of the world is not distributed equally or equitably, global politics and economics in my lifetime have been based on the assumption that there could be enough for all to live comfortably, even affluently, consuming at unprecedented levels, no matter how many of us humans might be roaming the Earth’s surface.

But things change. The United States is still the richest society, for the time being. Affluence is still considered the norm to strive for all around the world, for the time being. But that dream of endless expansion has left us facing nightmare scenarios for the future. Dramatic change is inevitable.

Today we face multiple, cascading ecological crises, including but not limited to rapid climate destabilization, accelerated species extinction and loss of biodiversity, chemical contamination of land and water, and soil erosion and degradation. These realities will require our species to down-power, either consciously through rational planning or as a result of larger forces beyond our control. Coming decades—not in some science-fiction future, but in the lifetimes of many of us—will be marked by permanent contraction. Like it or not, the future is not “more and more” but “fewer and less.” If there is to be a decent human future—perhaps if there is to be a human future at all—we must face the inevitability of fewer people consuming less energy and fewer material resources.

No one knows how the species will get there. No one knows if we can get there through rational planning. But our chances of maintaining a significant human presence on Earth, living in some fashion that we could call humane, will be enhanced if we let go of illusions about growth, whether they are tied to “drill, baby, drill” or a “Green New Deal.” The end of the fossil-fuel era is inevitable, and no combination of renewable energy sources can fuel continued expansion.

I have no comprehensive proposal for how we can get to “fewer and less,” nor does anyone else. The scale and scope of the challenge is unprecedented, and beyond the reach of conventional policy proposals. But we can enhance our chances of success by cultivating restless and relentless minds.

Restless, in the sense of never feeling settled or secure, because there is no security, something that vulnerable people understand and eventually will be daily reality even for the affluent.

Relentless, in the sense of being open to questioning every assumption, doubting every conclusion, pursuing every challenge—because the moment we think we’ve figured things out is the moment we will make our biggest mistakes.

Restless and relentless because we will fail often and need to develop the resolve to persevere, and because when we get something right it means that we’ll become aware of another set of problems just ahead.

And we should cultivate restless and relentless minds not just because of the challenges we face but also to foster a more joyful participation in the Creation.

I offer this not so much as admonition but as a report of my experience working with Wes Jackson. Although he squirms at the use of such a term, Jackson is an elder. That doesn’t just mean someone who is old, although he is that, clocking in at age 85. Nor does it mean someone who knows a lot and has done a lot. There are lots of old folks who have lived interesting lives and accumulated knowledge but don’t fit the bill. Elders are those people whose experience has generated wisdom, whose counsel is trustworthy. That doesn’t mean elders always have the right answers but rather that they generally know the right questions.

Jackson is an elder in two significant projects of the last half of the 20th century, the environmental education and sustainable agriculture movements, which emerged as people in the dominant culture realized what others in more vulnerable places long knew: the modern industrial world was, and remains, on an unsustainable trajectory. Jackson was around at the beginning of both those projects, making significant contributions while at the same time getting some things wrong, as he constantly reminds us. Elders recognize their mistakes and make sure others know about them, as a reminder of human fallibility.

Those two chapters of Jackson’s adult life—shaping early environmental education programs and then building an important sustainable agriculture research institution—have positioned him well for his third act: a blunt and honest reckoning with the fragile future we face. Through it all, he’s been well served by his restless and relentless mind.

Survival Studies and Natural Systems Agriculture

Before becoming a “certified intellectual,” Jackson’s gently mocking term for people with advanced degrees, he was learning about ecology and community on his family’s Kansas truck farm. Looking back, Jackson sees many lessons in the diversity of crops and animals, as well as the resourcefulness of people working without much capital in a relatively low-energy world. But change was coming, and it came quickly. In Jackson’s youth, teams of horses were replaced by tractors. Diversified small farms gave way to large farms with row after row of wheat, corn, and soybeans.

The knowledge Jackson gained through farm work was supplemented with formal education: a B.A. in biology at Kansas Wesleyan University in 1958, an M.A. in botany at the University of Kansas in 1960, and a Ph.D. in genetics at North Carolina State University in 1967. He taught biology at a Kansas high school and then at his undergraduate alma mater, at a time when students were pushing for more social relevance in courses. As Jackson became increasingly aware of the ecological crises, he proposed a Survival Studies program and also edited a book that collected early environmental writing, Man and the Environment, first published in 1971. But before that KWU program got off the ground, Jackson was tapped by California State University, Sacramento to establish and run one of the first Environmental Studies programs in the country.

Despite all the opportunities in California, Jackson was bristling at the limits of traditional universities, which he says encourage students to shoot for “minimal compliance rather than spontaneous elaboration.” He also was feeling pulled back to the prairie and his native Kansas. A one-year leave turned into two years before Jackson finally resigned his full professor position and with his family settled in Salina in 1976 to launch an alternative school they called The Land Institute. As the educational experiment continued, Jackson also started focusing on soil erosion and degradation, the ecological liabilities of annual grains grown in monocultures. Would it be possible to grow those grains, which make up about two-thirds of humans’ calories, in less destructive fashion? Were perennial grain polycultures possible? Could grain crops with sufficient yield be grown in ways that minimized plowing and chemical inputs?

Jackson was cautious about predicting success for what he dubbed Natural Systems Agriculture, saying it likely would be 50 to 100 years before the breeding program produced viable grain crops. That timeline was fine with him. “If you are working on something you can accomplish in your lifetime,” he says, “you’re not thinking big enough.”

Today, NSA is ahead of schedule. The Land Institute has developed a perennial intermediate wheatgrass called Kernza® that is in limited commercial production, and perennial rice is being grown in China. Breeders in Kansas and around the world also are working on perennial wheat, sorghum, legumes, and silphium (an oilseed in the sunflower family). Jackson retired when he hit 80, but the plant breeding and ecological intensification work continues. The Land Institute, which now collaborates with more than 50 researchers on six continents, launched the New Roots International project in 2020 to help facilitate the global community of perennial grain researchers and advocates.

Jackson retired, sort of. For the past five years he has been writing about his experiences and concerns, returning to the challenge of education and the limits of traditional institutions. That’s where my work with Jackson begins. The first project was to collect in one volume some of his key ideas. Jackson has been spreading these ideas in his own writing and speaking, but I wanted to see his most important insights organized and presented in a short, accessible book. I encouraged him to write that, but he was always busy with other projects. So, I decided to do it myself, with his cooperation, resulting in The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson: Searching for Sustainability. At the same time, Jackson was writing Hogs Are Up: Stories of the Land, with Digressions, a collection of stories from his life that illustrate those ideas.

Key Concepts

Jackson is the master of the aphorism, the pithy and memorable phrase that captures an important truth. My book is organized around those aphorisms, the most well-known of which may be Jackson’s suggestion that we focus not just on problems in agriculture, but contend with “the problem of agriculture.” Ever since humans became dependent on those annual grains, Jackson points out, we’ve been drawing down the ecological capital of the planet beyond replacement levels. There are better and worse ways of farming, but soil erosion and degradation have haunted us since we became farmers.

From that observation flows what I consider to be Jackson’s most important aphorism, his description of contemporary humans as “a species out of context.” We are smart, but for all our intelligence we routinely engage in behavior that may make a continued large-scale human presence on the planet impossible in the not-so-distant future. How did that happen?

Let’s start with the species’ timeline: Before the invention of agriculture and surpluses of grain starting 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, human beings were foragers. For the 2.5 million years of the genus Homo and almost all of the 200,000 to 300,000 years of Homo sapiens, hominins lived as gatherers and hunters. With few exceptions, we evolved in band-level societies typically no more than 50 people. There were many variations in human society, but these living arrangements generated relatively egalitarian social relations with little or no hierarchy. Humans gathered plant foods and hunted, typically ranging over a territory with frequent movement.

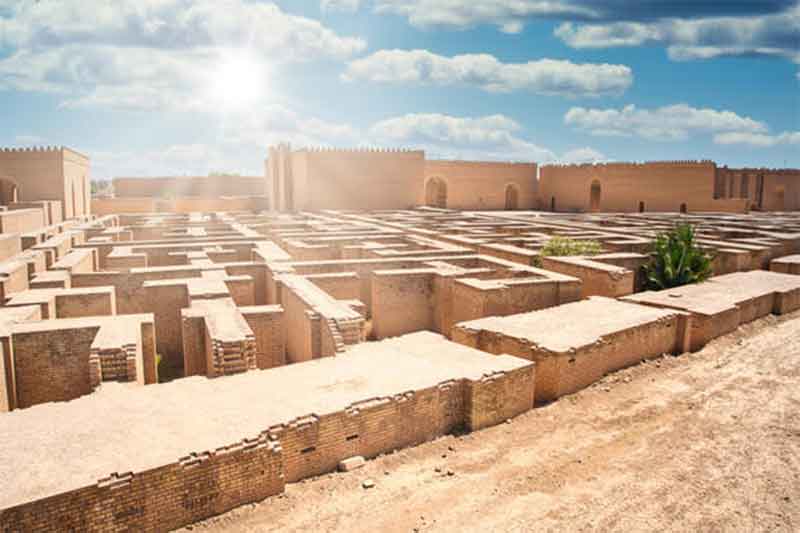

While there were limited forms of settled community life in some resource-rich places prior to agriculture, it was only after people started farming that we got cities, empires, nation-states—all forms of social organization based on hierarchy. Not all people in all places developed on the same trajectory—differences in climate, geography, and environmental conditions have shaped human societies—and in some places people rejected such organization. But eventually the size and scale of human communities in most places were far beyond anything we evolved in.

Because our evolutionary history shaped us for a very different way of living in much smaller social organizations, it’s not surprising how hard we have to struggle—and how often we fail—to make our out-of-context social systems work to everyone’s benefit. Most of our current social and ecological problems are a result of humans trying to live in political and economic contexts for which we are not adapted in evolutionary terms.

Jackson is not the first person to highlight this human trajectory, which is basic material in many anthropology courses. But in labeling humans a species out of context, he captures the problem we face in ways that both challenge and comfort us. We’ve messed up, but we aren’t the first humans to mess up, and we mess up so often because we’re struggling with living arrangements for which we aren’t optimally suited.

In short: We keep trying to remake humans to fit into contemporary societies. We might want to start asking how to remake contemporary societies to better fit humans. There’s no going back to foraging as our primary economy—not with nearly 8 billion people on the planet—but we can go forward with our evolutionary history in mind.

Jackson also suggests that our chances for success improve if we embrace an “ignorance-based worldview.” An awareness of our ignorance is not an endorsement of being stupid, but rather a recognition of the limits of human cognition. Again, Jackson is not the first person to point this out, but he conveys it in plain language that focuses our attention on limits. Given the complexity of the world, we are—and always will be—far more ignorant than we are knowledgeable. Jackson suggests that “we go with our long suit” and stop thinking we can answer every question and control every aspect of life. A deeper intellectual humility is appropriate and necessary.

When we lose sight of our limits, Jackson warns, we too easily embrace “technological fundamentalism.” This brand of fundamentalism assumes that the use of high-energy advanced technology is always a good thing and that the increasing use of evermore sophisticated high-energy advanced technology can solve our problems, including the problems caused by the unintended consequences of earlier technologies. This fundamentalism is based on the idea that human knowledge is adequate to run the world. But to claim such abilities, we have to assume we can identify all the patterns in the larger living world and learn to control all aspects of that world. That we so clearly cannot do those things does not seem to disturb the technological fundamentalists’ faith.

Experts have a role in coping with these problems, but the hyper-specialization that has taken hold in most universities won’t produce the thinking we need to face contemporary crises, according to Jackson. Because our problems don’t stay in separate categories, we need to “force knowledge out of its categories” and not be constrained by the boundaries of academic disciplines. We need to “ask questions that go beyond the available answers.”

We need restless and relentless minds that do not settle for the conventional wisdom—of the right, center, or left—to deal with those multiple, cascading social and ecological crises, which present problems that go beyond the available solutions.

Fragile Futures

Here’s a question that goes beyond the available answers, a problem that goes beyond the available solutions: How are we going to keep feeding 8 billion people—or more, given the expected increase to 9 or 10 billion before the population is predicted to stabilize—without accelerating the drawdown of the ecological capital of the planet?

That’s not a pleasant question to ask or an easy problem to ponder. But anyone who wants to be serious about sustainability should not turn away. In a forthcoming book, Jackson and I argue for facing such overwhelming challenges, starting with four hard questions:

- What is the sustainable size of the human population?

- What is the appropriate scale of a human community?

- What is the scope of human competence to manage our interventions into the larger living world?

- At what speed must we move toward different living arrangements if we are to avoid catastrophic consequences?

The first, the sustainable size of the human population, always includes a second implicit question: “at what level of consumption?” Raw numbers of people mean little if we don’t know how much energy and how many resources are being extracted from ecosystems to support those people’s “lifestyles.”

How many people, consuming how much stuff, can Earth sustain? No one knows, or can know, the answer. There are people—mostly the technological fundamentalists, the people who believe that gadgets will solve our problems—who believe we can continue full speed ahead because we can invent our way out of any crisis. Jackson and I reject that techno-optimism. We’ve all lived through a century of dreaming there are no limits to human expansion and consumption. The coming decades will require us not only to accept but embrace, and even learn to celebrate, limits.

But if there’s no way to know the answer to questions like this, why bother? Without certainty, some people argue that fussing about the future is a waste of time. But the choices we make today are always based on some assumptions about the future. Support for any version of contemporary politics and economics—whether one’s ideology is right, center, or left—that is based on the assumption of endless expansion is plausible only if one embraces technological fundamentalism. We believe that’s a dead end.

Is this the start of a tired lecture from the Global North telling societies in the Global South to practice better birth control? Not at all. A more pressing component of the ecological crises is the unsustainable consumption of the Global North, where we have become too skilled at death control, at extending human life. Too many people are being born, but just as crucial is that we can keep people alive so long (often with greatly reduced quality of life) that populations are increasingly out of balance. Better birth control, yes. But we also need to step back from the current obsession with death control and determine what constitutes a good life and how long such a good life needs to last.

These are, as Jackson says, questions that go beyond available answers and problems that go beyond available solutions. To get us focused on the scope of the challenges we face, I want to start with a few numbers and a bit of history.

In the first decade of the 20th century, the world population was 1.7 billion. When my father was born in 1927 and my mother in 1932, the population had grown a bit, to 2 billion. When I came along in 1958, there were just under 3 billion people. When my child was born in 1992, the population was 5.5 billion. Today, we’re closing in on 8 billion. In three generations, one person’s lifetime, the human population doubled and then doubled again. That’s unprecedented. That’s not going to work out in the long run. One place to see that is agriculture, where it’s already not working out, even though many believe we have “solved” the problems of food production.

All of those 8 billion people need to eat on a regular basis. But today about 700 million are food insecure, and 3 billion cannot afford a healthy diet. Many critics point out that there’s enough food to feed the world and that the impediment is unjust social and economic systems. That claim is accurate, for now, and radical social and economic changes are required to address that unjust wealth distribution. But no matter what social and economic systems we adopt, we will not have the capacity to feed this many people indefinitely.

These kinds of claims lead to the accusation that one is an unrepentant “Malthusian,” who like the 18th century economist Thomas Malthus either doesn’t understand technological progress or just doesn’t care about poor people. Malthus didn’t anticipate industrial agriculture and dramatic yield increases, of course, but the failure of his predictions doesn’t mean population growth can continue forever. The rapid expansion of the human population, temporarily defying the limits that all organisms face, is the temporary result of industrial processes, especially one industrial process.

In 1909, German chemist Fritz Haber developed a process by which atmospheric nitrogen (N2) could be converted into ammonia (NH3), a form of nitrogen that plants can use. A few years later, engineer Carl Bosch took Haber’s laboratory process to industrial scale, and by 1913 the chemical company BASF had a plant up and running. Since then the “Haber-Bosch process” has been the primary industrial method for producing synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, which has “solved” the problem of dwindling soil fertility and the depletion of organic sources of fertilizers.

That “solution,” which uses natural gas as a feedstock with a lot of heat (today about 1% of industrial energy goes to this process), has doubled food production. This suggests, as statistical analyses have borne out, that about half the current population would not be here without Haber-Bosch. From 1960 to 2000, there was an 800% increase in synthetic fertilizer use. That seems like a success, as long as we don’t mention that only about half of that nitrogen (depending on the crop and conditions) is taken up by the plants, with the rest washing into waterways and creating “hypoxic zones,” the dead zones in the ocean that have such a low concentration of oxygen that marine life suffocates; as long as we don’t mention that this method of producing more food has accelerated soil erosion and soil degradation; as long as we don’t mention that industrial agriculture is a key cause of species extinction and contributes to rapid climate destabilization. Our short-term success in increasing yields has undermined long-term resiliency, what Jackson calls “the failure of success.”

Rapid population growth that is underwritten by industrial agriculture, along with lifespans extended by energy-intensive high-tech medicine, should make us nervous. I’m not suggesting that I, or anyone else, know when this expansion will end. Again, let me stress the limits of humans’ predictive capacity: There is a big difference between predicting the timing of events in the future and doing our best to understand the trajectory of systems. Prediction is a fool’s game. To not attempt to deepen our understanding of the path we’re on would be even more foolish.

So, back to the hard question. Is the current 8 billion people at the current level of aggregate consumption sustainable? Is an even larger population, continuing to consume at current levels, sustainable? Given the rapidly declining health (from the human point of view) of virtually every ecosystem on Earth, I do not believe either of those possibilities is plausible. That means that we need to act today to make possible a future with fewer and less. Fewer people consuming less.

How many fewer? How much less? Again, no one knows or can know for certain. But as we make choices today, we have to make our best guess. For purposes of starting honest conversations about public policy, I assume the answer is no more than half the current population consuming no more than half the resources used today. That likely won’t be enough, but it’s a start. That’s not a prediction but rather a conversation starter. If your guiding assumptions are different, Wes and I want to know why. In an intellectually healthy society that strives for democratic decision-making, this is one of the most important conversations we can have right now. And it is one of the hardest conversations to have.

Reflecting on Our Ideologies, Rejecting Ideologues

Let’s return to my promotion of restless and relentless minds. Jackson says that he likes talking to people who are “objective, in the right way.” That’s a humorous way of acknowledging that it’s easy for us to believe that we have developed the correct framework for analyzing the world. Jackson also likes to remind us of the “problem of reassertion.” No matter how right we may think we are—and how right we may be about our framework and analysis—if all we ever do is reassert that analysis we won’t grow intellectually in ways that help us adapt to changing conditions.

In other words, Jackson acknowledges that we all work from an ideology but he tries to avoid being an ideologue. We need to be critically self-reflective about our own way of seeing the world.

“Ideology” is typically used in negative ways, such as when we counsel others to keep an open mind and “not be so ideological.” In that sense, an ideology is understood as a belief system that is too abstract and rigid, leaving one prone to fanaticism. People using the term this way imply that an ideology is something other folks have, which keeps them from seeing things clearly. The assumption is that there is a common-sense way of interpreting the world without resorting to a reality-distorting ideology.

This desire for knowledge untainted by value judgments leads some professions to claim to be non-ideological, yearning for a pristine notion of objectivity (as a former journalist and journalism professor, I know that game well). But rather than pretend that human knowledge is generated without assumptions and values, we can critically self-reflect—individually and collectively—about those assumptions and values.

We have all been in discussions where it seemed clear that the other person was not trying to look at all sides of a question but simply pressing a position out of an unreflective commitment to a belief system. If we were to be honest, we all can identify times in our lives when we exhibited the same rigidity. So, if we all have the capacity to get lost in ideology, who exactly are those people we can trust to have the undistorted common-sense vision? There are people who argue fanatically and seem incapable of real dialogue—people we appropriately label “ideologues”—but that should not lead any one of us to think we have the crystal-clear, non-ideological view.

A restless and relentless mind is comfortable with this aspect of human cognition. Some ideologies prove to be based on more accurate data and more compelling interpretation of data, but no ideological framework can guarantee a correct answer to every question in such a complex world. Better to say that some ideologies do a better job than others in guiding our actions, but that in the end no ideology completely captures the world.

If one isn’t comfortable with the term “ideology” we could instead use “worldview.” Jackson uses that term when he asks people to look beyond the differences between capitalism and socialism—differences that are, of course, real and important—in order to see the similarities in economic systems that preach expansion, celebrate consumption, and are dependent on high-energy/high-technology. Jackson suggests that we need to replace the current industrial worldview, which flows from an overly optimistic view of human cleverness, with an ecological worldview, which relies more on nature’s wisdom.

Joyful Participation

From this description, some might mistakenly assume that Jackson is a pretty depressing fellow. In fact, Jackson is relentlessly happy, though restlessly so. He sees dramatic changes coming, many of them potentially catastrophic but also some that will be healthy. In the meantime, there’s work to do and a world to enjoy.

There’s a saying in what is sometimes called the minimalist movement that “less is more”—a good life is not only possible but more likely when one reduces consumption. Fair enough, but I think it’s more honest to say “less is less, but less is OK.” It’s easy to recognize that people in affluent societies own too much stuff, and that an excess of stuff can be more of a burden than a blessing. But we also should recognize that there are advantages to having access to lots of energy and materials. Anyone who has ever spent all day digging a hole or a trench with a shovel, a task that a backhoe could accomplish in a matter of minutes, knows that sometimes lots of energy is easier on your back.

But life is tradeoffs, and we too often focus on the positive effects of energy and materials without considering the drawbacks. There’s no way to identify every cost and benefit, but we don’t even try to do full-cost accounting, in terms of the ecological, political, and psychological consequences of our technologies. We routinely emphasize the benefits and ignore the real costs.

As some anthropologists have suggested, we need to rethink our ideas about affluence, about what constitutes a good life. Marshall Sahlins puts it bluntly: “[T]here are two possible courses to affluence. Wants may be ‘easily satisfied’ either by producing much or desiring little.”

This takes us back to Jackson’s observation that we are a species out of context, that for most of our evolutionary history we were foragers who lived in small, relatively egalitarian bands that spent less time working to secure food and shelter than we do today, what Sahlins called “the original affluent society.” Surplus, ownership, and hierarchy were rare, existing only in places that were particularly resource rich.

The advent of large-scale grain agriculture, followed by what we call civilization, changed all that. We began working harder in more unequal societies, often with poorer diets and an overall reduction in human health. Agriculture led to settled communities, cities, empires, and the modern nation-state, and along the way we got writing and an expansive, permanent record of human creativity in the arts. We also got hardened inequality, not only in economic systems but also in patriarchy and later in white supremacy. We got air conditioning and we got global warming. We got the internet and internet pornography. We got social mobility and the ability to leave behind small communities when they limit our personal development, along with the erosion of a sense of stability and meaning as communities atrophied.

Honest full-cost accounting would consider all these complexities of contemporary societies—the pluses and the minuses—so that we can start to make rational collective decisions about what we want to hang onto during the down-powering. This will not be easy, and often it will not be fun. Down-powering will mean suffering, even if we can manage to become more humane in caring for each other.

Less is less, but less has to be OK because we have no choice. The sooner we realize that, the more time we have for rational planning to reduce the pain of a transition to a new way of organizing our lives.

Once we come to terms with that, Jackson believes we will open ourselves up to a more joyful participation in the Creation. Jackson doesn’t believe in a creator God, but he has reverence for an ecosphere that is constantly changing, constantly creating this larger living world of which we are a part.

That awareness of the beauty and complexity of the world started for Jackson on his family’s farm. His formal education in biology, botany, and genetics deepened that reverence. Both everyday experience and scientific knowledge have been part of the process by which Jackson came to see the distress of ecosystems, starting with agriculture. Learning about the crises developed alongside learning about the beauty and complexity.

Jackson was out walking on his property in Kansas one spring day and called me with a simple question: “Why is this not enough?”

Jackson ticked off a list of the plants he had cataloged on the walk and described a spider web between two trees that he had been studying. He talked about all the questions about those organisms that arose as he observed them.

“Why is this not enough?” Jackson asked. Why are the sights and smells of the world, along with the questions that the world generates, not enough for us humans? Why are these everyday questions about that creative ecosphere not enough? Why do we need male sky gods? Do we really need to dream about colonizing Mars? What if sky gods and Mars colonies are the sign of an atrophied imagination?

Indeed, why is this not enough?

We can find the authentic underpinnings of meaning and purpose in our own engagement with the world around us. All of this—the seeing, the smelling, the pondering, the emotions that arise in us when we talk about it all—can be enough. If we can be satisfied with what the ecosphere gives freely to us—if that truly can be enough for us—perhaps we can find the strength to ask the hard questions and the imagination to go beyond the available solutions. Our restless and relentless minds can get to work.

A version of this essay was presented as the keynote address for the online conference on “Changing Configurations and New Directions” at Ajeenkya DY Patil University in Pune, India, on July 27, 2021.

Robert Jensen is an emeritus professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin and a founding board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center. He collaborates with the Ecosphere Studies program at The Land Institute in Salina, KS. Jensen is associate producer and host of Podcast from the Prairie, with Wes Jackson. Listen to episodes a SoundCloud or wherever you get your podcasts.