Canons of Character from Shambhu Chandra Vidyaratna’s Vidyasagar Jeevan-Charit O Bhramaniras

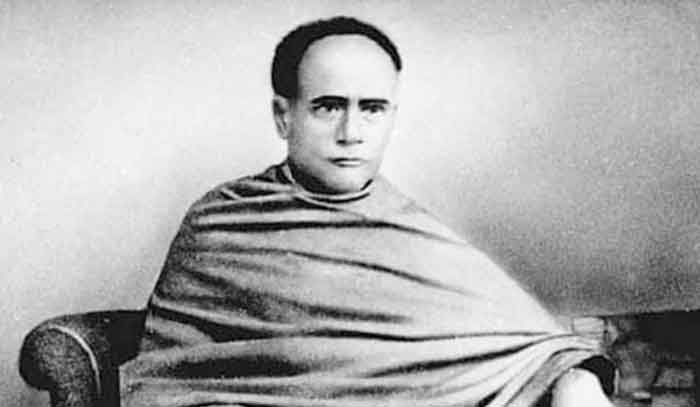

(This is part II of a 2-part article on one of the leading figures of the 19th-century Bengal renaissance- the scholar, educationist, humanitarian and social reformer, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar. (Read Part I ) The translations presented here, and possible future installments are episodic excerpts extracted from the biographical text in Bengali by ICV’s 3rd younger brother, Shambhu Chandra Vidyaratna. The excerpts presented herein, as in Part I, highlight ICV’s significant interactions with leading English administrators, from school and college levels all the way to Lieutenant Governors and even the Governor General of the British East India Company. These highlight his emergence as one of the founders of modern Indian education, in particular the education of women. MRC)

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

…. In the year 1847, (following the advice of the Principal of Fort William College, Mr. Marshall) Agraja published the Bengali translation of Vetal Panchavingshati from Hindi. Per understanding, the Principal of Fort William College deposited 100 copies of the book to the college library to be perused by the civilians; the government paid 300 rupees for the same. This sum covered the printing cost. Of the remaining 400 copies, Agraja [venerable older brother, an Indian mode of address- MRC] donated 200 to friends and family members. A book of such quality had never before been published in Bengali. As a result, Agraja received much praise at home and abroad. Via Vetal Panchavingshati alone, Agraja gained great renown throughout Bengal. People from all social strata expressed great eagerness to read the Bengali Vetal Panchavingshati since it had poetic structure of a very high order. Students at Sanskrit college and other educational institutions would learn Bengali writing skills by studying the Bengali Vetal Panchavingshati. It must be acknowledged by all that Vidyasagar was the pioneer in the education of students in the Bengali language. He was also the Guru in the matter of ushering in the modern Bengali language writing and teaching. …..

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

…. Even from his childhood, Agraja would often wonder why it was that women and girls were not allowed to receive any education. Why in fact were they denied access to gaining knowledge their entire lives? Likewise, how could one make it possible to eliminate the evil polygamy practiced by the Kulin Brahmins (an orthodox group within the Brahmin ranks which practiced intermarriage and of course in many cases, polygamy, sometimes with child brides)? According to him, as he became more well-informed, this was very much against the shastras (Hindu moral codebooks); as long as such evil practices were not eliminated from this land, there would be nothing but misery for the Hindus of Bengal.

When a child bride would encounter widowhood (often a consequence of a much older man marrying a girl child- MRC), he would become deeply aggrieved. One day, when the twelve-year-old daughter of a relative became widowed, Mother (ICV’s) became utterly distraught and began weeping. When Agraja attempted to console her, both Mother and Pitri-Deva (venerable Father) earnestly posed the question (to ICV)- “Is there no provision made in the Dharma Shastras for the remarriage of child widows? Were the law-makers truly this heartless?” These heart-rending words from his parents became etched in his heart.

That same year, Agraja was appointed Examiner for Bengali writing by senior students from Hindu, Hooghly, Krishnanagar and Dhaka Colleges. He put forth an examination question regarding whether or not Indian women ought to be permitted to pursue education. Nilkamal Bhaduri from Krishnanagar College was judged to have written the most outstanding essay on the subject, and received a gold medal from the Government. At the award ceremony for the competing schools, the Education Council President, the Honorable (John Eliot) Drinkwater Bethune (a major figure in establishing modern education, especially women’s education, in Bengal and India; a renowned women’s college in Kolkata is named after him- MRC) spoke at great length to the issue of establishing women’s education at these colleges. Moreover, portions of the award-winning essays were read in Hon. Bethune’s presence at the same award ceremony. Subsequent to the above efforts, many accomplished and enlightened individuals began earnest work in advancing women’s education throughout India. …

Meanwhile, Professor of Literary Studies Madanmohan Tarkalankar left his position at Sanskrit College to assume the post of Learned Judge in Murshidabad. Soon after, there was a vacancy in the position of Professor of Poetics. Consequently, Dr. Moyt, Secretary of the Education Council, expressed to Agraja his intention to assign to him the vacant post. Agraja initially turned down the offer; however, upon Dr. Moyt’s sincere request, he informed him, “If the faculty appoint me to the position of Director of Literary Studies, then I may consider accepting the position as of now.” Thereafter, in December, 1850, he was appointed Director of Literary Studies with a salary of ninety rupees. A good friend, Babu Rajkrishna Bandyopadhyay was then a Cashier at Jardine House. Upon Agraja’s request and recommendation, the Secretary of Fort William College appointed Rajkrishna Babu to Head Writer at the College.

While he was serving as Director of Literary Studies at Sanskrit College, Secretary Rasamay Dutta resigned from his post. At this point, Agraja was assigned, and completed a report on the strategies to improve Sanskrit College. Until then, the role of a Principal was being jointly fulfilled by the Secretary and Assistant Secretary of the College. Following the submission of Agraja’s report, the two positions were abolished, and Agraja was appointed Principal of Sanskrit College at a salary of one hundred and fifty rupees. He then invested much of his time finding ways to improve the functions and effectiveness of the College. He appointed Srishchandra Vidyaratna professor of Literary Studies. He arranged to have several textbooks which had become unavailable, to be re-printed, an action which greatly benefited the students. He arranged to have Raghuvamsa and Kumarasambhava reprinted along with the acclaimed commentary by Mallinath. A vast population of students across the Bengal region benefited greatly from these actions, having access to typed and printed versions of previously hand-written books. …..

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

….. About six or seven months after he was appointed Principal, Agraja fell seriously ill. Upon partial recovery, he continued to suffer from frequent headaches and toothaches. After some treatment, he improved somewhat, however, the headaches continued to afflict him. Several months later, another devastating blow was dealt to the education community of Bengal. My Agraja’s closest ally, member of the Bengal Legislative Council, President of the Education Council, genuine benefactor of India, major sponsor of education among the masses, the noble Mr. Bethune [John Eliot Drinkwater; note the truly generous tributes offered to one of the English colonials’ genuinely honorable figures in Indian history- one ranking alongside William Carey and David Hare. These are major names in world history. MRC] was taken by Mahakala [an expression implying falling to Father Time, or dying- MRC].

…. The Sahib (Mr. Bethune) would frequently prod the Government to open schools in mofussil villages. Turns out it was his prodding which resulted in Governor General Dalhousie taking the initiative towards opening village schools. No doubt, his efforts have been of inestimable value to the people of this land. It was India’s misfortune that Mr. Bethune was taken by death before he could further advance education in Indian society. Mr. Bethune’s cortege arrived at the burial ground. Both Agraja and Lt. Governor Halliday rode in the same carriage to attend the ceremony. More than one thousand students from the various schools and colleges were also in attendance.

… Following Mr. Bethune’s funeral, the Governor General [in 1851, that would be (the controversial) Lord Dalhousie- MRC] took charge of the Bethune Female School, and appointed the Secretary of the Home Department, Sir Cecil Beadon and Vidyasagar the President and the Secretary (without pay) of the school respectively. Thanks to his (ICV’s) sincere efforts, the female school began to improve significantly. By engaging the serious opponents of female education via committee assignments and counsel, he was even able to get the daughters of antagonist families (such as the family of Shova Bazar’s Raja Kalikrishna Bahadur) admitted into the Bethune Female School. It was Vidyasagar Mahasay who first persuaded Mr. Bethune to campaign for women’s education. Without his sincere efforts, female education would not advance in this country, and the Bethune Female School would have ceased to exist. ….

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

…. Around this time [1851 and after- note that this was only slightly before the Sepoy Mutiny and the transfer of Indian governance onto the hands of the British monarchy- MRC], the benevolent Sir (Frederick James) Halliday assumed the very first Lieutenant Governor’s post in India. Meanwhile, the most capable Secretary of the Education Council, Dr. Moyt, went back to England for a short period of time. Sir Halliday now instituted some fundamental changes to the administration of the education system. He re-named the Education Council so that it was now known as the Public Institution. And he replaced the post of Secretary with Director, appointing Gordon Young to that post. Observing these changes, Vidyasagar Mahasay advised the Lt. Governor as follows- “Appointing a young civilian to this senior post may not have been a wise decision; he knows virtually nothing of the ways of life and cultural norms in this province. He is young, inexperienced, and somewhat haughty; he has only recently arrived in India, and knows little about this province- learning some of that will require more time. Dr. Moyt was the Secretary of the Education Council for many years, it would have been a far better choice to have Dr. Moyt be assigned the Director’s post.” Hearing thus, Sir Halliday responded, “I have every intention to oversee the operations of the institution personally from now on. Mr. Young’s role will be symbolic. I suggest you teach Mr. Young aspects of the work of a Director of public education for two months. Mr. Young is quite intelligent, I expect him to learn quickly.” Thus instructed, Vidyasagar Mahasay thereafter would visit the Director in his office every so often for several months, and offer him advice and guidance, whereby Mr. Young soon became quite skilled in his post. For the months that he received training under Agraja, Mr. Young held Vidyasagar Mahasay in very high regard. …..

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

… In those days, women in this province would not receive any education. It was in Birsingha [ICV’s village of birth- MRC] that the very first school for girls was established. Every girl attending school would receive her books for free. When the Bethune Female School was established in Calcutta, many of the leading and aristocratic figures of Calcutta society stood in opposition to it. However, when the school for girls opened in Birsingha, most neighbors gladly sent their daughters to school. Moreover, even those from neighboring villages were in full support of this initiative. Initially, the girls’ school curriculum included Bengali, Sanskrit epics and Grammar. Later, the Sanskrit literature was curtailed in favor of English and formal Sanskrit. Agraja allocated three hundred rupees for the monthly salary of the Master and Pandit at the school. An additional one hundred rupees were allocated monthly for book. Agraja’s dear friend Babu Pearycharan Sarkar would offer the girls his “First Book,” “Second Book,” “Third Book” and others for free. Vidyasagar Mahasay would spend one hundred rupees each month on the pharmacy, the compounder and medicines, in addition to another thirty rupees on miscellaneous expenses. He would also donate fifteen rupees each month for the Night School [these provisions compare most favorably with the great reluctance towards even minimum wage for working families in the US to this day, almost two centuries later- MRC]. ….

[I will conclude this introductory sampling of snippets from an extraordinary life with two other service-related anecdotes. It must be noted that in this 2-part presentation, I have not presented anything regarding ICV’s even more path breaking actions and campaigns, particularly relative to matters such as Widow Remarriage, repealing Polygamy, repealing Child Marriage, and countless other instances of social injustice. I will consider taking those critical issues, visited via the eyewitness accounts of Shambhu Chandra Vidyaratna, in follow-up articles- MRC.]

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

…. In the early 1850s [note that ICV’s most active period in life coincided with such major historic events in colonial India as the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857- ICV’s outlook vis-à-vis the Mutiny and its effect on his interactions with the colonial administrators will also be a subject of future discussion- MRC], a certain Mr. Pratt and two other English colonial administrators were appointed School Inspectors. The inspectors were engaged in correspondence with the colonial administrative leaders back in England. A short while earlier, having been instructed to establish a great many schools in Bengal’s hinterlands directly from England, Agraja had proceeded to do so with his characteristic vigor. However, the newly-appointed Director, Mr. Young, remained inactive towards these initiatives. Consequently, Lt. Governor Halliday and the three school inspectors misinterpreted Mr. Young’s inaction, and advised Agraja to cease any further school establishment projects. However, since Agraja continued his planned rural projects, the Director reported this to the Lt. Governor. The Lt. Governor thereafter called Agraja to his office, and there ensued considerable arguments from both sides. Sir Halliday then reported the matter to the administrators in England. (Most interestingly) the administrators in England responded by ordering the Lt. Governor to immediately commence the opening of rural schools, and extended most generous compliments to Agraja for all his efforts. This, of course, led to serious falling out between Agraja and Mr. Young, and this is what eventually led to Agraja resigning from his academic post. ….

[Excerpted from Chakuri– sketches from his years in service]

…. During his tenure as Principal of Sanskrit College, Vidyasagar Mahasay had to visit the Lt. Governor at his home every Thursday. The Lt. Governor instructed Agraja to discard his traditional sandals, dhoti and chadar, and instead put on pantaloons, chapkan (a traditional long coat), pugree (a headdress common in Northern India), formal shoes and socks for his visits. Therefore, Agraja put on an outfit as suggested by the Lt. Governor a few times. However, such an outfit being well outside the tradition of his people, he would feel embarrassed and tormented as though he were in chains. Hence, one day he informed the Lt. Governor, “This, Sir, will be my last visit with you. Henceforth, I shall be unable to put on this non-traditional outfit, whether or not I can retain my employment.” Upon hearing this, the Lt. Governor extended to Agraja the permission to put on whichever attire he was comfortable with. For virtually his entire life, he would appear in nothing but the simple, dignified Bengali garb of dhoti, chadar and sandals. Only in his much older years, faced with ailments due to aging, he would sometimes put on flannel shirts and shawls. …..

Dr. Monish R. Chatterjee, a professor at the University of Dayton who specializes in applied optics, has contributed more than 130 papers to technical conferences, and has published more than 70 papers in archival journals and conference proceedings, in addition to numerous reference articles on science. He has also authored several literary essays and four books of literary translations from his native Bengali into English (Kamalakanta, Profiles in Faith, Balika Badhu, and Seasons of Life). Dr. Chatterjee believes strongly in humanitarian activism for social justice.

Selected excerpts translated by Monish R Chatterjee ©2021