by Thomas Klikauer and Meg Young

It has often been said that predictions are hard to make – particularly when they concern the future. We have seen it many times in recent years and this may just as well apply to the upcoming federal election in Germany scheduled for 26th September 2021.

Unlike the USA’s first past the post system with one-person one-vote, Germans have, funnily, two votes. One vote goes to the candidate in a local electorate and the second vote goes towards proportional representation.

As a consequence, Germany is not defined by two parties. It does not have Democrats vs. Republicans (USA), Labor vs. Tories (UK), or as some evil heretics might say, “Coke vs. Pepsi”. Instead, several parties seek to govern after an election.

This makes coalition building “after” an election crucial. Unlike in previous decades, coalition building will be the name of the game in about one month’s time. The upcoming coalition comes at a time when Angela Merkel is ending her reign and will move into retirement.

The next coalition government is also harder to predict because of Germany’s moving political landscape. For one, there is Germany’s Neo-Nazi party – the AfD – which is now established in German politics. Next, there is the stratospheric rise of the environmental party and the Greens. All of this makes predictions on who might win the election somewhat more complicated than usual.

On the whole, six political parties are likely to enter Germany’s next parliament. The rest – failing to gain at least 5% – will not enter Germany’s federal parliament. These six parties are the aforementioned:

- Neo-Nazi party AfD – using the deceptive name “Alternative for Germany” to camouflage their racism, xenophobia, Nazism, etc.;

- the strong-state favoring CDU (Merkel’s party) with Armin Laschet as Merkel’s successor ;

- the neoliberal-free-market FDP – out to support the rich in getting even richer;

- the Joe-Biden-like social-democratic SPD – Germany’s traditional majority ex-working class party;

- the progressive environmentalist The Greens – a party that used to be progressive but, as some say, has mutated into a kind of Bio-FDP (ecological soft neoliberalism); and finally,

- the Bernie-Sanders-like progressives, the Linke (the left) – with strong voters’ support in the former East-Germany. Historically, it is the party that Germany’s reactionaries made to suffer the most starting with Bismarck’s Anti-Socialist Laws; in the 1918/19 revolution, Noske’s free corps, i.e. the Vanguard of Nazism, murdered their party’s leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht; barely 15 years later, the Nazis tortured its party members to death and put the rest in concentration camps; Post-Nazi Germany banned the party (KPD) in 1956, while welcoming ex-Nazis into Germany’s post war institutions; in the 1970s and 1980s, its member were tormented with Berufsverbote. Between 1949 and 1990, its Eastern setup (SED) was running East-Germany until the party converted itself into Die Linke in the 1990s.

To make things easier, Germans have assigned colors to these six parties. Merkel’s CDU gets black. The AfD (should be brown) but is often shown as blue. The AfD’s natural coalition partner remains the CDU. Yet, the CDU (black) has declared that no black-brown hazelnut coalition with the AfD (brown) will be possible.

If the CDU is to be believed, there will be no repeat of the 1933 DNVP-NSDAP coalition between German conservatives and German Nazis. The neoliberal FDP gets yellow. The SPD gets red (sometimes light red); the Left gets red or violet; and for obvious reasons, the Green gets green.

Since Germany’s elections are generally held on a Sunday – no Super Tuesday in Germany – Germans have something they called the Sunday-Question. It asks, who would you vote for if next Sunday is an election?

The latest Sunday-Question was held on 21st August 2021. It showed: CDU: 22%; SPD: 22%-23%; Greens: 17%-18%; FDP: 12%-13%; AfD: 10%-12%; and the Left: 6%-7%. Based on the eventual election result, seats in Germany’s parliament are distributed after following complicated mathematics.

Germany’s parliament has about 600 seats (depending on the byzantine mathematics of the relationship between the two votes each German has). It is predicted that Merkel’s conservative CDU might get about 160 seats; the SPD is set to gain about 135 seats; the Greens: 115; FDP: 75; AfD: 70; and, the Left: 45.

Once the seats are distributed towards Germany’s next parliament, coalition building will begin. Yet, many have already started to play the hypothetical game of a possible future coalition government.

In any case, Germany will have a coalition government. No political party will have the support to win more than 50% of Germany’s voters. Rather, the opposite has happened in recent years. There is an ever increasing fragmentation of Germany’s electorate with three parties (CDU, SPD and Greens) getting roughly 20% and, the rest is divided by the three smaller parties: AfD, FDP, and The Left.

Among the many coalition options that are currently discussed, one outcome of the next election might be the so-called traffic light coalition consisting of SPD (red), FDP (yellow) and Greens (green).

Next, there might also be the so-called Kenya coalition (because of the colors in Kenya’s flag). This would be a black (CDU), red (SPD) and Green coalition. Finally, there are two more options: the so-called Jamaica coalition (CDU, FDP & Greens; and, the so-called Germany coalition consisting of CDU (black), SPD (red) and FDP (yellow). These are the seven most likely options for a coalition (ranked in accordance to voters’ support):

- An Environmental-Center coalition: the strongest among all possible coalitions would be the environmental-center “Kenya Coalition” of CDU, SPD and Greens which conjure up about 67% of Germany’s voting population.

- A Conservative Coalition: the so-called Germany Coalition (CDU, SPD & FDP) would represent about 61%.

- An Environmental-Neoliberal Coalition: a Jamaica Coalition (CDU, FDP & Green): 58%;

- A Progressive-Neoliberal Coalition: a Traffic Light Coalition (SPD, Greens & FDP): 55%;

- A Progressive Coalition: a truly progressive red-red-green (SPD, Left & Green) would fall a little short of the 50% majority margin coming in at 49%;

- A CDU/SPD Coalition: a continuation of the present CDU/SPD coalition (without Merkel) might get 48%; and finally,

- A Conservative-Environmental Coalition: CDU/Green coalition (currently governing Baden-Württemberg) would only have the support of 45% of all German voters.

According to many predictions, it is likely that Merkel’s successor – the conservative and not much loved Armin Laschet might become the next chancellor. More recently, polls show SPD’s Olaf Scholz ahead of Laschet. In terms of popularity, unloved Laschet has recently been overtaken by the new rising stars. In the last few days, the rather boring Olaf Scholz (SPD) has gained in support. Finally, there is the calm and sensible Annalena Baerbock (Greens).

Overall, one might say that Germany’s polls are constantly occupied by daily politics and media appearances and this will only intensify before the election. Almost every day there are reports of new poll leaders and the disgrace of those parties that lose a percentage point here and there. Recently, the SPD was gaining in popularity even running ahead of the much favored Greens. It was for the first time that this happened for months that SPD overtook Merkel’s CDU.

To view Germany’s election foremost as a contest between the arch-conservative Armin Laschet who failed bitterly in the recent flood crisis, the dreary but solid Olaf Scholz, and newcomer and very level-headed Annalena Baerbock is extremely dangerous. The decision as to who will be Germany’s next chancellor will be made during negotiations for the next coalition government. Usually, the party with the greatest voters’ support is set to be nominated as the next chancellor.

Prior to the election, these predictions are part of political campaigning, tactics, and strategies. There is a good reason to treat current surveys – particularly on who will be the next chancellor – with extreme caution. Just four weeks out of Germany’s election, these candidates stand far less for the expected election outcome than for a weekly and often daily tendency in public likings.

First of all, election polls should not be confused with forecasts. Public polling before an election do not give an outlook on the election outcome. They simply show a kind of a political snapshot on the day a poll was conducted.

In fact, there is a general underestimation. There is a somewhat distorted picture of the real support for the right-wing extremist AfD. In the first place, the AfD’s support base is less likely to participate in polls. Secondly, its supporters are also less likely to disclose their party preference when asked.

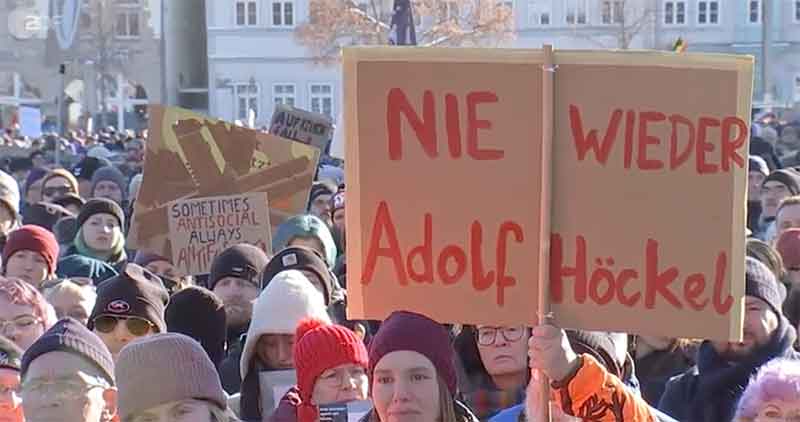

Pollsters assume that this is because voting for the AfD is socially less accepted than voting for a democratic party. Beyond that, the AfD remains Germany’s most controversial – and often most hated – political party. Calls like “no more Nazis” at AfD rallies against the AfD are not uncommon. And, “Grannies Against Nazis” are also seen.

While the AfD can be underrepresented in polling, the Greens tend to be rather overrepresented. In addition, not all social groups are reached equally well by pollsters. Not everyone can answer the phone during the day. And beyond that, pollsters found that the willingness to participate in public polling has declined sharply in recent years.

So, what does all this really mean for Germany’s next election? Firstly, it means that the above-noted possible election outcomes still have a substantial margin of error of about 2.5%. So, in reality, the values of these parties can vary by plus or minus 2.5%.

The support for the SPD, the Greens and Merkel’s CDU could potentially be around the 20% margin. On the other hand, the CDU could just as well go up to 24.5% – even though its current trend is downward. In view of all of this, it would be just as wrong to prematurely declare:

- the Greens to be defeated;

- the CDU on an unrecoverable downward trend; and

- the SPD on a never ending upward trend.

In reality, any one of Germany’s three front runners could still leave the others behind. The next polling problem hits these big three political parties – CDU, SPD & Greens – disproportionally. The larger the share of support for a party in a survey, the more inaccurate the estimation on their actual support may be. This also works the other way around.

Projections for Germany’s smaller parties (AfD, FDP, The Left) are often more accurate. These two mechanisms were evident in past elections. As a consequence, survey results have been relatively stable for small parties over a long period of time – but not so for Germany’s big three parties.

Overall, one might say that who will win in Germany’s election next month can hardly be determined by such surveys. The idea of the more surveys the better simply does not work. Yet, the structural shortcomings of public polling remain. Worse, it does not go away as the more polling one carries out. Examples of the problem of polling can be found in recent history.

Before Brexit, polls saw the side of EU supporters ahead – Brexit won. Before the 2016 US presidential election, many polls pointed out that not Donald Trump, but Hillary Clinton would sit in the White House – Donald Trump was in the White House. In both cases, as is well known, things turned out differently than predicted.

Meanwhile in Germany, just five weeks before the last election in 2017, several polls saw Merkel’s CDU sitting at 38% to 40%. Yet, in September 2017, the CDU got just 32.9% – significantly less than predicted. In 2017, pollsters faced a similar predicament for the SPD. All three cases – Brexit, Trump and Germany in 2017 – polling did not match the actual outcomes.

As for Germany’s 2021 election next month, the following picture seems to emerge. Merkel’s CDU has lost about 7% in public polling in which the decline began in July 2021. Meanwhile, the SPD has gained up to 6% and continues to rise – almost on a daily basis.

One might say that the political mood in Germany is in motion. Yet, the election outcome is far from decided. While public polling a few days before an election “can” (note: “can”) reflect the result relatively precisely, there is still a lot of room for ups and downs in the last month before the election.

These ups and downs are also found when it comes to predicting a possible coalition government. On this, 36% of Germans think that a Jamaica coalition is most likely. This would mean that the conservative CDU, the neoliberal FDP and the environmentalist Green would form a government with, most likely, the not much liked Armin Laschet, as the next chancellor. And, with the below 10% thinking that the current coalition (CDU & SPD) will continue.

Virtually, the same number of people think that Germany will be governed by a progressive coalition consisting of the reformist SPD, the semi-socialist Bernie-Sander-like The Left party, and the environmentalist Greens.

This so-called “red-red-green coalition” remains the most progressive option that Germany has to offer. Yet, these three (SPD, Left and Greens) might end up just a touch below half of all the seats in Germany’s federal parliament. A majority of seats is needed to form a progressive government.

Yet even if Germany’s progressives would gain enough seats to form a government, there are still two more problems namely: history and Hessen.

Since the early 20th century, Germany’s majority socialist (SPD) and minority socialist (socialist and communists) have shown a great disliking towards each other. This started with the SPD’s support for the disastrous Kaiser’s World War I in the year 1914. While mutual distaste continued all through the Failed Revolution 1918/19.

During the 1918/19 revolution, SPD’s strongman Gustav Noske said the faithful words, “someone must become the bloodhound”. Noske and his reactionary and semi-Nazi militias, mercenaries, and killer squads – the so-called free corps – shot a large number of German workers ending the revolution. Only a few years later, social-democrats and communists fought each other again. At that time, Germany’s Nazis marched into Germany’s parliament ending German democracy.

The second problem for a truly progressive coalition is the state of Hessen and with what happened in 2008. In that year, Hessen’s election outcome favoured a progressive coalition consisting of SPD, The Left and Greens – the aforementioned red-red-green coalition.

The three parties – SPD, Greens & Left – had gained 57 seats compared to the bourgeoisie (CDU) and petit-bourgeois (FDP) bloc’s 53 seats. Yet, party-internal quarrelling inside the powerful SPD prevented a progressive coalition with the Left.

The SPD’s so-called “Nosek-Wing” is, at least ideologically, still carrying on their old and time-honoured hatred of the socialists (The Left). During coalition negotiations in the state of Hessen, the Noske-Wing got the upper-hand and declined to support a progressive red-red-green coalition. As a consequence, coalition building ended in a catastrophe – CDU and FDP marched into government.

All this means is that, even in the most unlikely case that in the upcoming federal election next month, even if the majority of Germans would indeed vote for a progressive red-red-green coalition government, the SPD’s Noske-Wing might reject this – just like it did in Hessen. As a consequence, is very likely that right-wing social-democrats will put a conservative-reactionary government place rather than the socialists Left party – they detest with a passion.

Only a few years ago, this is what had happened in the state of Hessen. And, about 100 years ago, the same had happened in 1918/19 when the SPD’s Noske literally killed the revolution. It then happened again in 1933. Social-democrats were fighting against evil communists and Hitler’s Nazis marched into government.

One might say that this is all history and that it is all dead and buried. Not quite though, as the SPD’s hatred of the socialists (the Left) remains so powerful, as seen in 2008 in Hessen. This loathing prevented a progressive coalition in the state of Hessen in 2008. And, it may very well be repeated in 2021.

The right-wing of the SPD might very well – again – prefer the destruction of a progressive coalition which will open the way for the future chancellor of Germany: Armin Laschet (CDU). This is likely to happen unless recent predictions continue and that Olaf Scholz will become the next chancellor in an environmental-center coalition of SPD, CDU and The Greens.

Thomas Klikauer has 700 publications and writes regularly for BraveNewEurope (Western Europe), the Barricades (Eastern Europe), Buzzflash (USA), Counterpunch (USA), Countercurrents (India), Tikkun (USA), and ZNet (USA). His next book is on Media Capitalism – Hegemony in the Age of Mass Deception (Palgrave, 2022).

Meg Young (GCA and GCPA, University of New England at Armidale) is a Sydney Financial Accountant & HR Manager who likes good literature and proof reading.

Originally published in CounterPunch