The ongoing Covid pandemic has affected the Raika and Rebari community in Rajasthan, known to herd camels for a livelihood for centuries.

The Raika community, who are pastoralists, have been facing hardships since 2015 with the decline in the camel population and its trade but the outbreak of Covid has put them on the brink of economic disaster. The community was already badly impacted by the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015, that hurt its regular sales, but their miseries have doubled in the last two years.

“Our community has faced hardships in many forms over the years, but we have fought through it all. But this time our source of sustenance is at risk. We are unable to sell any of our camels. The sale had already become difficult with the ban on transportation since 2015. But we could at least sell some to the locals at camel fairs. But during the pandemic the camel fair has been stopped and there is no way to sustain ourselves now”, says 48-year-old Ram Narayan Raika, who lives in Jodhawar Ki Dhani in Pali district of Rajasthan. Narayan and his family of eight members owns 12 camels and are dedicated to camel breeding.

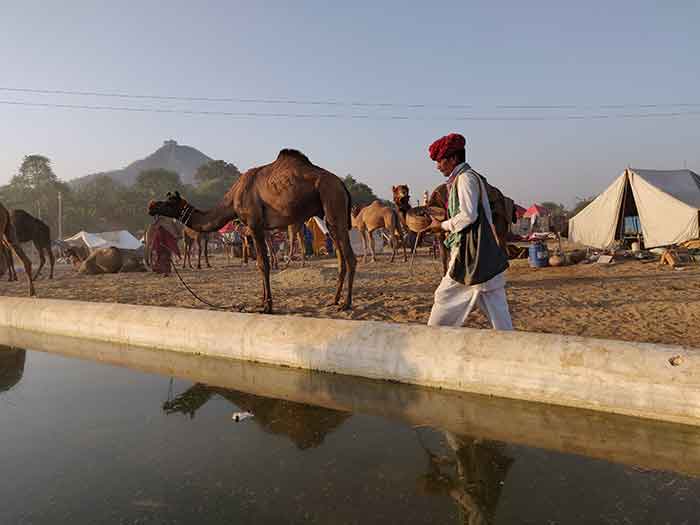

Camels have been one of the major sources for the survival of many indigenous communities living in the state of Rajasthan. For generations, these communities have been rearing different breeds of the camel for fulfilling the basic necessities of their lives.

“I used to earn around 6000 rupees per month through my camels, which I used to send for farming. Another major income was selling camels through the animal fairs. But nothing has happened since the Covid-19 outbreak took place. Earlier I would have earned Rs 10,000 for a one-year-old camel but now there are no takers”, added Narayan, who is now forced to work as a labourer in the nearby village.

“I now prefer to work at a construction site to feed my family. At home, my wife and two elder daughters take care of camels”, he added. Ram Narayan is not alone. Many from his Dhani (village) are facing similar problems, forcing them to join some other daily wage work to feed their families. The village is dominated by the Raika community. As per Ram Narayan, Jodhawar Ki Dhani was home to at least 2000 camels a decade ago. The numbers came down to 400 after 2015 and now the figures are depleting further.

The 20th Livestock Census, released in 2019, shows that in 2012, the total number of camels in the Rajasthan was 325,000. By 2019, the numbers had dipped to 213,000, a dip of almost 35 percent in just seven years. However the local camel breeders say the actual number is even lower currently, at 150,000. The camel was recognized as the state animal of Rajasthan in 2014.

It was considering the declining rate of camels in Rajasthan, that the Rajasthan state cabinet introduced the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015. The Act sought to stop the export of camels outside the state territory for slaughter. Exports for all other purposes were allowed, but only with the approval of recognized authorities.

To stem the decline in the camel population, the state government also started a Camel Development Scheme in 2016, that gives an incentive of Rs. 10,000 for every new born calf in three instalments. However many breeders could not avail of this incentive.

The activists working for the welfare of the camel and the breeders have demanded the amendment in the 2015 Act. According to them the new Act has not increased the camel population and instead hit camel sales hard.

“The government should allow the sale of camels outside the state and their use as transport medium which is banned under the new law. This affects the economy of camel owners”, said Hanwant Singh Rathore, director of Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan, a body of camel breeders in Rajasthan.

The ban in the trade across the state border has slashed the animals’ price by a massive margin, making living difficult for (Raika and Rebari community) breeders, who are either forced to abandon their animals, or indulge in the illegal trade. According to camel traders, both young and adult male camels would be sold earlier at a handsome price. Now, the price of the animal has dipped so much and the losses have been so high that breeders have had to sell all their camels at a low cost.

“At the Pushkar camel fair or Nagaur camel fair, a six-month-old camel calf was earlier sold at Rs. 10,000- Rs 15,000. But in absence of any other earnings and out of desperation now it is sold at Rs. 1000-1500”, Rathore added.

The Tilwada, Nagaur and Pushkar Mela (also known as the Pushkar Camel Fair), are annual fairs in which domestic animals, mostly camels, horses, and cattle are traded with buyers from across the country. But the fair has been put on hold by the Rajasthan government ever since the pandemic outbreak took place.

The pandemic hits camel milk production

Another blow to the Raika and Rebari community has been a hit on camel milk production in the pandemic.

As an alternative means of livelihood, breeders had begun to sell camel milk. But during the pandemic, due to the rising cost and lack of transportation, the demand went down.

” Camel milk has often been claimed to be beneficial for autism, diabetes, liver disease, jaundice, even cancer. Through this, a family can earn between Rs. 18,000 to Rs. 30,000 a month but the competitive pricing in comparison to cow’s milk or buffalo’s, and a lack of demand among the general populace because of inadequate marketing has hit its selling power”, said Hanwant who ran this initiative at the Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan.

” Camel milk has often been claimed to be beneficial for autism, diabetes, liver disease, jaundice, even cancer. Through this, a family can earn between Rs. 18,000 to Rs. 30,000 a month but the competitive pricing in comparison to cow’s milk or buffalo’s, and a lack of demand among the general populace because of inadequate marketing has hit its selling power”, said Hanwant who ran this initiative at the Lokhit Pashu Palak Sansthan.

On September 17, this year the Minister of the animal husbandry department, Lal Chand Kataria, while answering a question in the Rajasthan state assembly, said the main reason for the decline in the number of camels is the continuous development of mechanical resources and availability of a high level of transport facilities down to the village level. The minister also said, “Under the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act 2015, there is a ban on the slaughter of camels and taking them out of the state without official permission, due to which the use of camels is continuously decreasing”.

The minister also announced the starting of oonth shalas or camel shelters, similar to cow shelters, to stop decline in camel population in Rajasthan

According to sources, the Rajasthan government might amend the 2015 Act to allow the sale of camels outside the state. Since the Act was brought in place, police has arrested 21 people and recovered over 230 camels, which were being smuggled out.

On September 2, this year the Rajasthan high court also took suo moto cognizance of the sharp decline of the camel population in the state. Advocate Prateek Kasliwal who has been appointed as amicus curiae to suggest changes in the law enacted in 2015 said, “I have been conducting meetings with the stakeholders associated with camels and their sustenance. We shall present a report soon in the court”.

Livelihood of those associated with tourism impacted

Besides the breeders, the livelihood of those involved with the tourism industry have also been affected. Salman Ali, who owns six camels and used to ferry tourists in Jaisalmer is finding it hard to survive.

“There are hardly any tourists coming to Jaisalmer. Before Covid I used to earn at least 12 thousand rupees per month, now it has declined to Rs 3000, which is insufficient to run a family of six members”, said Ali, a resident of Jaisalmer.

According to the experts in the tourism industry, there is a need for special focus on the camels as well as the Rebari and Raika communities.

“Besides promoting camel and camel rides, the state government should also highlight and organise tours to traditional dwellings of these communities. The Raika and Rebari dhanis should be put on the tourist map of Rajasthan. It will give a chance for tourists to explore India beyond what they see. The government should make these visits economically viable for the breeder community who will share their culture and stories with the visitors”, said Tripti Pandey, a Rajasthan based author who writes on culture and tourism.

Tabeenah Anjum is a journalist based in Rajasthan, reporting on politics, gender, human rights, and issues impacting marginalised communities. She tweets @tabeenahanjum