A report by PUCL Karnataka on the Hate Crimes on Christians in Karnataka, 2021

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Criminalizing the Practice of Faith, A report by PUCL Karnataka on the Hate Crimes on Christians in Karnataka, 2021, traces the hate crimes perpetrated against Christians in Karnataka by Hindutva groups.

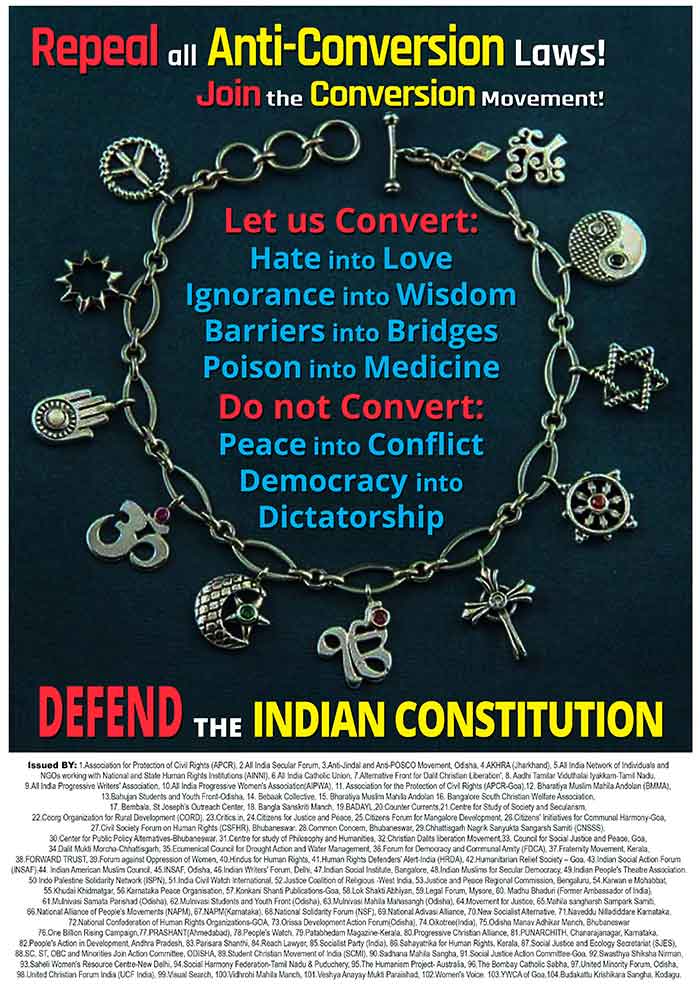

The point this report seeks to make is that the myth of conversion remains a bogey which is used to target the constitutional right to practice, profess and propagate religion as recognized under Article 25. What emerges in shocking detail in that in today’s Karnataka, using the language of ‘conversion’, Christians constitutional right to practice and profess their religion is being curtailed. Even with respect to conversion it should be noted that the right to choose remains a core part of one’s fundamental right to freedom of religion, expression and dignity and ought not be curtailed under the Indian Constitutional framework.

The Need for the Report

In the context of rising hate crimes against the Christian community, the series of surveys ordered into their practice of faith and the statements of the Chief Minister, Home Minister expressing their keenness to introduce the Anti-conversion bill in Karnataka, that this report is being written to document the persecution of a minority community.

The report documents 39 incidents of hate crimes against Christian in Karnataka from January till November 2021. Given the frequency and intensity of these attacks, our report relies on the Christian community’s narratives of surviving majoritarian violence. The members of the Christian community especially in rural Karnataka continue to face threats of violence, discrimination and survival in the course of their everyday lives. Keeping this in mind, to avoid any increased threat to the survivors, the names of the respondents in the report are changed. This report specifically documents:

a) The attacks on Pastors, believers and Churches in Karnataka from January – November,

b) The modus operandi of the Hindutva groups behind these

c) The patterns that emerge from these

The team made calls and visits to pastors across Karnataka, who have faced different kinds of attacks motivated by communal forces in their areas. This was done to document details of narrations as well as provide any legal support that may be required. While this narrative report has been written after talking to 39 pastors from 39 separate incidents in 2021, there are several other cases that are neither reported in local media, nor could access resources or networks for legal and financial assistance. Much before this report, APCR, UCF and United Against Hate published a joint report detailing more than 300 incidents of attacks

Christians in less than nine months.1 It is a remarkable documentation that truly provides an idea into the scale of attacks happening all over the country. This report takes a more geographically-specific approach and focus on Karnataka. It also provides a larger framework of hate crimes to understand these attacks.

Even without an anti-conversion law the attack on the Christian minorities has been a weekly affair. Such a bill is likely to only make matters worse for the Christian community by giving Carte Blanche for excesses by vigilantes.

To holistically look at these series of hate crimes against Christians, the report is structured to begin with elaborating on the patterns of hate crimes that have emerged in these attacks.

Chapter 1, titled Patterns in Hate Crimes identifies six patterns namely, (a) assault on the right to freely practice religion, (b) living under threat in a post pandemic Karnataka, (c) Perpetrators of Hate Crimes, (d) Casteist Slurs as an attack on Dignity, (e) Attacking the vulnerable among a marginalised community and (f) Police Complicity in Hate Crimes. Then, the long-term impact that marginalises the community further, is evaluated.

In most cases, Christians have been forced to shut down their places of worship and stop assembling for their Sunday prayers. Effectively, these attacks on praying in a gathering, that is enforced by Hindutva groups with the complicity of the State functions as a bar on the freedom to practice religion itself. Far from the right to propagate religion, today the attacks in Karnataka are actually on the right to freely profess and practice religion.

When pastors are threatened by the Hindutva groups to shut down these prayer meetings, it is not only a gross violation of their right to religious freedom, but it also robs an entire community of their right to dignity and the right to life defined as psychological well-being.

During the pandemic when thousands more lived on the brink of survival, instead of focusing on people-centric governance, the state was complicit in antagonizing those praying. In many cases of mob violence, the police arrested pastors and believers. They even issued formal notices to churches to stop prayer meetings. This failure of the State, further marginalizes a minority community in how they live their lives struggling to access education, shelter, food, livelihood and basic dignity during COVID.

The perpetrators behind these communal hate crimes in all the 39 instances are Hindutva organisations, namely Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Bajrang Dal, Hindu Jagrana Vedike. In two instances of hate crimes in Karwar (October 4) and Mandya (January 25) Bharatiya Janata Party MLA Sunil Hegde and 3-time BJP MLA Narayana Gowda (currently Minister of State for Youth Empowerment and Sports, Planning, Program monitoring and Statistics) were also named as people who supported the police in targeting Christians. A new organisation name that has emerged from the accounts is that of Banjara Nigama. This organization appears to be small but rather violent.

What is particularly alarming is the discrimination and social boycott that the Christians have faced from persons who are not a part of these Hindutva organisations. Such as their own neighbours, landowners, employers, small businesses like grocery stores, even schools, in their localities.

In almost all instances of prayer meetings were disrupted or violently attacked, a common pattern is that the language used in the verbal abuse primarily consisted of casteist slurs. These casteist slurs must be seen in the context that Christians in rural India largely comprise of daily wage workers, agricultural labourers and people from Dalit communities.

In any typical attack on churches, the first thing that vigilantes do to disrupt prayers, is to demand from the believers, their family names and the caste in which they are born into. The situation soon escalates, as they abuse the pastor and believers by using derogatory words and phrases that insult people based on their castes and casteist stereotypes. These statements are an assault on the constitutional provision of prohibition of untouchability and on the dignity of the individual.

Why does this happen? What does caste have to do with the decision of converting to Christianity? Ambedkar in a speech titled, “Why go for conversion”2 explains that conversion in fact is the path that leads to equality, he says,

“According to me, this conversion of religion will bring happiness to both the Untouchables as well as the Hindus. So long as you remain Hindus, you will have to struggle for social intercourse, for food and water, and for inter-caste marriages. And so long as this quarrel continues, relations between you and the Hindus will be of perpetual enemies. By conversion, the roots of all the quarrels will vanish… thus by conversion, if equality of treatment can be achieved and the affinity between the Hindus and the Untouchables can be brought about then why should the Untouchables not adopt the simple and happy path of securing equality? Looking at this problem through this angle, it will be seen that this path of conversion is the only right path of freedom, which ultimately leads to equality. It is neither cowardice nor escapism.”

The omnipresence of caste and untouchability in Hinduism makes conversion a means to achieve individual freedom and equality. The rigidity of the caste system and continued oppression of the SC/ST’s especially by the Hindutva groups ensures that individuals choose leave Hinduism.

Women and children are also at the receiving end of such physical assault. Hindutva groups use language that is casteist, sexually explicit and derogatory against women, and in cases where women have tried to respond to violence, they molest and sexually assault them.

Almost in every instance of mob violence studied in this report, it can be observed in the chain of events that the police have colluded with Hindutva groups. With the overt guidance of the local leaders of BJP, RSS, Bajrang Dal, Hindu Jagrana Vedike and Banjara Nigama, the police actively work to criminalise the lives of Christians and stop them from organising prayer meetings. This complicit role of the police emboldens a culture of intolerance and bigotry. Through the complicity, police have become an arm of social segregators strengthening of such Hindutva forces.

At this juncture, it must be noted that the law on the role of the police is abundantly clear. As per Section 154 of the CrPC3 the police as soon as they have information are required to take action. Especially when communal hate crimes through physical, verbal, sexual violence are being perpetrated in the presence of the police itself, the police have no excuse to not initiate action through filing FIRs against the miscreants.

The psychological impact of such a vast range of hate crimes carried out by neighbours, police officials and Hindutva leaders has severely affected their livelihoods, food security and general well-being.

Chapter 2, titled ‘Genesis of the Constitutional Freedom to Practise, Profess and Propagate Religion’, we look at the constitutional genesis of fundamental right to religion. This gives us the immediate contrast between what the legal reality ought to be and what the ground reality actually is. It provides us the historical background in which Article 25 of the Constitution was articulated.

Babasaheb Ambedkar piloted Article 25 through the debates and was clearly one of the main forces behind the text of Article 25. The freedom to practice, profess and propagate religion was at the core of his philosophy and his life trajectory embodies a commitment to the idea that one must have the freedom to convert as an essential part of one’s fundamental rights. It bears reminding that it was Babasaheb Amebedkar who said that, ‘I was born a Hindu because I had no control over this but I shall not die a Hindu.’ Towards the end of his life, he converted to Buddhism on October 14, 1956 along with half a million of his followers. Till today, October 14 or the day of Dharma Diksha is celebrated by millions of his followers.

However, the broad emancipatory vision which underlies Article 25 was not understood by the judiciary in its 1977 decision in Rev Stanislaus v State of Madhya Pradesh4 (delivered in the backdrop of the emergency) which narrowed down the broadly phrased constitutional freedom to propagate.

The decision in Stanislaus must be reconsidered in the light of the 2015 decision in Puttaswamy v Union of India5, which has recognized the right to privacy as a fundamental right. The Supreme Court held that, ‘privacy is the ultimate expression of the sanctity of the individual. It is a constitutional value which straddles across the spectrum of fundamental rights and protects for the individual a zone of choice and self-determination.’

When Christians pray in churches or pray in their homes, they are doing nothing more than exercising their right to profess and practice their faith. This attack by right wing elements is nothing other than an attack on the right to profess a faith and practice a faith, leave alone propagate a faith. If these hate crimes are allowed to continue then Article 25 will survive in name only.

Chapter 3, The irony of Freedom of Religion Law, traces the post-independence legal history of the freedom of religion laws in the different States of India. It highlights the shifts that the law has taken and its contribution to the criminalising the practise of faith.

Currently, “Freedom of Religion Acts/Ordinances” exist in some shape and form in 9 States, namely, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat.

Over the last five decades, there are four shifts in the text of the law that allow for these freedom of religion laws to be weaponised against members of the minority religious community even more than before.

Firstly, the prohibition of conversion now includes conversion for marriage or vice versa, and goes on to declare marriages done solely for the purposes of conversion or conversion done solely for the purposes of marriage as null or null and void both. This blanket bar on conversion as an ancillary for marriage undermines an individual’s most inherent and fundamental right to choose that is constitutionally guaranteed.

Secondly, the shift that is observable today is in the nature of offence that forcible conversion is – from a cognizable offence, today it is a non bailable offence. This makes bail extremely difficult for the accused, especially given the reality that large numbers of people that are targeted through these Freedom of Religion Acts are marginalized and unable to afford legal support.

Thirdly, the reversal of burden of proof on the person who attempted to convert/converted/abetted conversion that he/she/they did not convert by fraud/force/misrepresentation/coercion/allurement or for marriage. This places a disproportionate burden on the accused to prove themselves innocent. Such a disproportionate burden changes the presumption in criminal law of innocence to guilt of the accused.

Fourthly, the law has moved from requiring to provide an intimation to the District Magistrate regarding conversion to now requiring a prior permission/application to be made in advance along with a declaration of conversion in a prescribed format. It even prescribes the District Magistrate the power through the police to inquire into the “real reason, purpose and cause of the conversion”. Failure to follow the procedural nuances of these declarations is criminally actionable that can be initiated by the District Magistrate. This reflects the lens of suspicion that all conversions are viewed under law. This suspicion has translated to the media coverage, forming the public perception that conversion inherently is wrong and illegal.

Chapter 4, Deciphering media narratives on the myth of conversion, deciphers the media narratives on the myth of conversion and identifies the contribution of the Kannada TV media imposing Hindutva views on conversion by exploiting the technique of investigative journalism and sensationalising the issue of conversion. We see that the media coverage is a mix of specious arguments, misleading statements, outright falsehoods, one-sided reporting and bias in favour of Hindutva forces and against Christianity. The reports are mostly sensationalist in nature, often deploying the device of ‘sting operations’ as if someone had been caught doing something illegal, whereas constitutionally, the activities are not only legal but an exercise of fundamental rights.

Chapter 5, Moving Forward with Resilience, discusses the resilient response of the community to the hate crimes and the need of the hour to collectively oppose the so-called anti-conversion bill in any form.

It leaves with questions that are begging to be asked from the State, Media and from people of Karnataka. And finally, we demand the implementation of the comprehensive list of recommendations by the State, the media, the civil society and Members of the Legislative Assembly.

The report notes that as responsible citizens, silence will cost us the remains of our secular democracy. To protect our constitutional values of equality, dignity, fraternity, the following questions must be asked to our fellow citizens, our media, our judiciary, our legislature and our government:

- Why am I as an individual concerned with another person’s faith?

- How can anybody but I decide what religion and faith I practise?

- What authority do the Hindutva mobs have, to decide what is forced conversion, and what is one’s choice of religion?

- In a rule of law society, can a person commit offences of criminal intimidation, grievous hurt and sexual assault, as if accusing a person of conversion legitimizes these offences?

State:

- What has the State done about any of these 39 hate crimes against Christians?

- What role does the State have in controlling the religion/faith of an individual?

- Why is the State thinking of bringing an anti-conversion bill when the current Freedom of Religion Acts have very few people who are convicted under them?

- Why is the State interfering in an individual’s faith against the mandate of the Constitution?

- Why are the police taking law into their own hands and increasing the vulnerability of Christians to hate crimes?

- Why does the State want to deny it’s citizens their fundamental right to practise religion?

Media:

- Which channels have covered any of the 39 incidents of hate crimes against Christians?

- What gives the channels the power to enter into people’s homes and treat them as criminals for practising their religion?

- How can channels violate our right to receive neutral, objective, impartial information as news consuming public?

Recommendations:

The Report makes various recommendations which are summarized below:

The State government must:

- Implement the directions issued by the Supreme Court in Tahseen S Poonawalla v Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354] regarding cases of mob violence and lynching strictly. This includes among others, registration of an FIR without delay, preventing harassment of family members of victims, ensuring cases of mob violence are tried by Fast Track Courts on a day-to-day basis, and holding police officials who fail their duties in preventing the violence

- Immediately formulate the victim compensation scheme as directed in Tehseen Poonawalla under Section 357A of the CrPC for the victims of hate In the said scheme for computation of compensation, the State Governments shall give due regard to the nature of bodily injury, psychological injury and loss of earnings including loss of opportunities of employment and education and expenses incurred on account of legal and medical expenses. The said compensation scheme must also have a provision for interim relief to be paid to the victim(s) or to the next of kin of the deceased within a period of thirty days of the incident of mob violence/lynching. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Implement the directions issued by the Supreme Court in regard to mob violence, in Kodungallur Film Society & Anr v Union of India [(2018) 10 SCC 713], pertaining to Structural and preventive measures, Remedies to minimize impending mob violence, Liability of person causing violence, Responsibility of police officials and Compensation.

- Take immediate steps for the holistic implementation of Guidelines on Communal Harmony, 2008.

- For every instance of vandalism of properties, especially of Prayer Halls, appoint a Claims Commissioner to assess the damage to public/private property, injury to persons, and award compensation by affixing liability on the perpetrators of the crimes and the organizers of the riots, as per the directions of the Supreme Court vide in In Re: Destruction of Public & Private Properties v State of AP and Ors [ AIR 2009 SC 2266].

- Designate, a senior police officer, not below the rank of Superintendent of Police, as Nodal Officer in each district, assisted by a DSP rank officer, to (i) take measures to prevent incidents of mob violence and lynching (ii) constitute a special task force so as to procure intelligence reports about the people who are likely to commit such crimes or who are involved in spreading hate speeches, provocative statements and fake news (iii) Hold regular meetings (at least once a month) with the local intelligence units in the district along with all Station House Officers of the district so as to identify the existence of the tendencies of vigilantism, mob violence or lynching in the district (iv) take steps to prohibit instances of dissemination of offensive material through different social media platforms or any other means for inciting such The Nodal Officer shall also make efforts to eradicate hostile environment against any community or caste which is targeted in such incidents. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Identify Districts, Sub- Divisions and/or Villages where instances of lynching and mob violence have been reported in the recent past, say, in the last five years. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Issue directives/advisories to the Nodal Officers of the concerned districts for ensuring that the Officer In-charge of the Police Stations of the identified areas are extra cautious if any instance of mob violence within their jurisdiction comes to their notice. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Broadcast on radio and television and other media platforms including the official websites of the Home Department and Police of the States that lynching and mob violence of any kind shall invite serious consequence under the law. Tehseen Poonawala Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Set up special helplines to deal with instances of mob Kodungallur Film Society and Ors. vs. Union of India (UOI) and Ors. [(2018) 10 SCC 713]

The police must:

- The Director General of Police/the Secretary, Home Department of the concerned States shall take regular review meetings (at least once a quarter) with all the Nodal Officers and State Police Intelligence heads. The Nodal Officers shall bring to the notice of the DGP any inter-district co-ordination issues for devising a strategy to tackle lynching and mob violence related issues at the State level. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- If it comes to the notice of the local police that an incident of lynching or mob violence has taken place, the jurisdictional police station shall immediately cause to lodge an FIR, without any undue delay, under the relevant provisions of Indian Penal Code and/or other provisions of law. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- It shall be the duty of the Station House Officer, in whose police station such FIR is registered, to forthwith intimate the Nodal Officer in the district who shall, in turn, ensure that there is no further harassment of the family members of the victim(s). Tehseen Poonawala Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Investigation in such offences shall be personally monitored by the Nodal Officer who shall be duty bound to ensure that the investigation is carried out effectively and the charge-sheet in such cases is filed within the statutory period from the date of registration of the FIR or arrest of the Accused, as the case may Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- Especially in cases of caste atrocities where casteist slurs are hurled, immediate FIR’s under the Prevention of Atrocities Act, 1989 must be

- Wherever it is found that a police officer or an officer of the district administration has failed to comply with the aforesaid directions in order to prevent and/or investigate and/or facilitate expeditious trial of any crime of mob violence and lynching, the same shall be considered as an act of deliberate negligence and/or misconduct for which appropriate action must be taken against him/her and not limited to departmental action under the service The departmental action shall be taken to its logical conclusion preferably within six months by the authority of the first instance. Tehseen Poonawala vs. Union of India [AIR 2018 SC 3354]

- If a call to violence results in damage to property, either directly or indirectly, and has been made through a spokesperson or through social media accounts of any group/organization(s) or by any individual, appropriate action should be taken against such person(s) including Under Sections 153A, 295A read with 298 and 425 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Kodungallur Film Society and Ors. vs. Union of India (UOI) and Ors. [(2018) 10 SCC 713]

- When any act of violence results in damage to property, concerned police officials should file FIRs and complete investigation as far as possible within the statutory period and submit a report in that Any failure to file FIRs and conduct investigations within the statutory period without sufficient cause should be considered as dereliction of duty on behalf of the concerned officer and can be proceeded against by way of departmental action in right earnest. Kodungallur Film Society and Ors. vs. Union of India (UOI) and Ors. [(2018) 10 SCC 713]

The members of the legislature must:

- Oppose the tabling of the draft Anti conversion Bill in Karnataka Legislative Assembly as well as the Karnataka Legislative Council.

The members of civil society must:

- Extend its solidarities and equivocal support to the Christian community through legal

- Vehemently protest against the Anti-Conversion

- Practice associated living and form solidarities across communal and caste divides

- Organize programmes that promote inter community interactions and thereby promote fraternal relations among various

- Educate the public on the need for intervention when acts of hate crimes occur so that their Constitutional rights are

The members of the media and self-regulatory bodies must:

- Abide by the Program and Advertisement Code and Code of Ethics and Broadcasting Standards in all its

- Stop sensationalising the myth of forced

- Actively report on the hate crimes perpetrated against Christians so that people of Karnataka know the ground

- News Broadcasting and Digital Standards Authority as well as the District Level Monitoring Committee most promptly initiate action against news media that is in violation of the Program and Advertisement Code and Code of Ethics and Broadcasting

The State Human Rights Commission, State Minorities Commission must initiate action against the violations of human rights by Hindutva groups.

Notes

2 https://velivada.com/2017/06/01/why-go-for-conversion-speech-by-dr-b-r-ambedkar/

3 https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1980578/

4 (1977) 1 SCC 677, https://main.sci.gov.in/jonew/judis/5403.pdf

5 (2017) 10 SCC 1