by Dr. Prashant Kumar Choudhary and Madhubrota Chatterjee

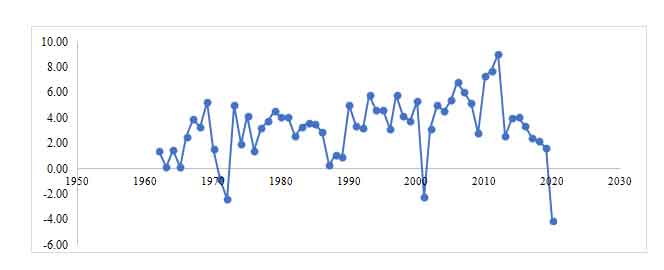

Sri Lanka is facing its worst economic crisis in the past fifty years; its economy has registered the lowest GDP per capita annual growth -4.1% in 2020, which is lower than its previous worst economic downturn of 2001 (GDP per capita annual growth was -2.25%). It is not the case that its economy was not recording signs of distress in pre-pandemic years; pandemic made the economy worse (as shown in Figure 1). Several macroeconomic indicators of the country show a steep decline over the years more so after the outbreak of the Covid pandemic such as employment, growth rate, foreign reserve, etc. Subsequently, there is a rise in inflation which has accelerated to 14% according to the National Consumer Price Index in December 2021, for the second consecutive month after inflation recorded a double-digit high in November 2021. This led to the high price of daily consumer goods exorbitantly (national consumer price index to 11.2%) which many Sri Lankans cannot afford to buy. For example, food prices went 6.3% while non-food items rose to 1.3% in December.

Pandemic has affected the economy of the country badly because of the imposed restriction on travel. According to World Travel and Tourism Council, more than 2 lac people lost jobs during the pandemic from the travel and tourism sector which contributes 10% of its GDP. According to World Bank estimates, more than 5 lac fell below the poverty line since the inception of the Corona-induced pandemic. With high dependency on tourism, pandemic depleted the country’s foreign currency reserve to one of its lowest ever. As of November 2021, it was just $1.6bn. In the post-pandemic period 2019, it was approximately $7.5bn.

In addition, the country’s currency, the rupee has lost 1/5th of its value and continues to slide further which limits its ability to buy food items from another country at a cheaper price. Several incidents were put on front describing the vulnerabilities the Sri Lankans are facing, especially the purchase of milk powder which is still on hold as the country only imports and widely consumes the powder in place of fresh milk.

Figure1: Annual GDP per Capita Growth (in %) Source: World Bank Dataset

The agricultural output of the country was exacerbated due to the ban of chemical fertilizers by the government last year which resulted in a decline in agricultural produce and price rise in essential food items. The hasty decision by the government to force farmers to adopt organic farming without making them prepare for the change led to widespread hoarding of the fertilizers and eventual crackdown by the government. Ultimately, there was widespread chaos and confusion at the government-owned shops of the Sri Lankans to buy food grains at a cheaper price. However, many argue that to blame the country’s move towards organic farming is just one of the several reasons the country was dealing with in the pre-pandemic period such as Chinese intervention in the island nation.

The crisis is also deleteriously impacting other sectors such as rubber. There have been imposed power cuts at peak hours because of its inability to obtain fuel as the electricity board has large unpaid bills. On the other hand, rubber plantation workers are facing wage cuts, getting less attention from the government despite being the 3rd most important export from the country.

Debt Crisis and Debt Trap:

China has lent money to Sri Lanka for the construction of ports, highways, airports, coal power plants during the last decade, the crucial being the Hambantota port and Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which faced severe criticisms from the US calling it a “debt trap” for developing countries, thus getting vulnerable pressure to repay from Beijing.

Sri Lanka has to pay a huge foreign debt to countries like China, India, and Japan; mostly to China which owes more than $6bn which has to be paid in coming years. Sri Lanka will repay the approximate debt of $7.3bn in a year (this comprises a $500m International Sovereign Bond). This is an uphill task for the country to fulfill the promises of repaying the debt as it had just $1.6bn foreign currency reserves available at its disposal.

Additionally, Sri Lanka is forced to pay $5m worth of tea every month to Iran as part of its oil bill. This would again hurt the economy adversely as it cannot continue repaying its debt in kind for a longer period of coming time. The country has to find both the short and long-term measures to deal with its economic woes.

Way out of Economic Crisis

In recent times, many countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America got the bailout package from the IMF, the World Bank to avoid bankruptcy threats. The Sri Lankan government is still having a round of talks with the cabinet for the bailout plan to be forwarded to the IMF for the reasons of stringent conditionalities imposed by international financial institutions such as the IMF. Meanwhile, India has provided financial support of $1bn to the country and Sri Lanka hopes to get another $1.5bn aid to maintain its economy running for the time being. Both the countries are working on the issues of lines of credit for medicine imports, food, fuel, currency swaps, debt postponement from India to Sri Lanka, and completion of the Trinco-oil farm project.

In the short run, the country might try to get some more financial assistance from other countries such as Japan or the USA but these aids would not be sufficient unless its macroeconomic indicators are not taken care of such as inflation, the balance of payment, employment, and economic growth, etc. On all these counts, the country’s poor performance and the pandemic stretch is laying doubts for the improvement in its economic situation, at least not in this year. Soon, it needs to focus more on BoP (balance of payment), foreign reserve, and simultaneously tacking inflation and employment which can be too much to manage swiftly.

Dr. Prashant Kumar Choudhary works as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Kumaraguru College of Liberal Arts and Science, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. He has completed his PhD in Political Science from the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore, and holds interest in research areas, such as Socio-economic policies, Electoral Politics, Women’s Health and Migration.

Madhubrota Chatterjee is an ICSSR (Indian Council for Social Science Research) fellow in Population Studies at the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. She is currently working on her thesis about Population Ageing, and holds research interest in Gender issues and geriatrics.