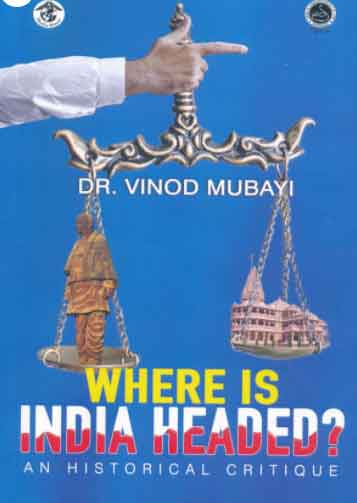

Book Review: Where is India Headed? An Historical Critique by Dr Vinod Mubayi, Media Society and Sahithya Pravarthaka, 2021.

It was April 2017, UP elections had just concluded, writing about the loss of composite culture, the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, Vinod Mubayi, in his essay UP Elections and Consequence said, ‘the early signs are not reassuring’. The essay foretold that the country was entering a phase where the formal constitutional proprieties of a liberal democratic state were likely to continue in a formal sense, but empty in content. The essay dwelled on the electoral propaganda of the BJP in 2017 for the consolidation of the Hindu vote bank, the growing appeal of the right-wing populism and the limited options that the divided opposition offered in the larger fight against fascism. This 2017 essay reads like a commentary on 2022 as we head towards another bitter election in UP. The title Where Is India Headed? captures this sad reality.

In this 341-page anthology, Mubayi brings together around 70 insightful short essays that capture the social and political reality of India and what holds for this country in the future. The essays comprehensively cover the period between the UP elections of 2017, and the Bengal elections of 2021, and the Bihar elections of 2020 in between. Secularism, Peace, Social and Economic justice, threat of Majoritarianism, Authoritarian State, Casteism, Fascism, Pandemic and suffering of the marginalized and the poor are some of the themes that these essays cover. The vast ground covered in the book fully achieve the twin objectives which this book sets to achieve. As described in the Preface, the book aspires to share with the readers the perspective of the left and progressive South Asian diaspora in the US and Canada and celebrate the life of one of its founders and leading light of the progressive diaspora movement, Comrade Daya Varma. We learn about the INSAF Bulletin (the acronym for Justice in Hindi and Urdu), the digital mouthpiece of the progressive diaspora perspectives. INSAF Bulletin began in May 2002 under the inspirational editorship of Daya Varma and after Daya Varma’s passing in 2015, the mantle passed to Mubayi who had been closely associated with the Bulletin since 2004. The critical essays in this volume were published in this Bulletin over the years. The volume is important not only for its commentary on the five crucial years in the contemporary history of India, but it introduces us to a lesser-known side of the Indian diaspora in North America.

In this 341-page anthology, Mubayi brings together around 70 insightful short essays that capture the social and political reality of India and what holds for this country in the future. The essays comprehensively cover the period between the UP elections of 2017, and the Bengal elections of 2021, and the Bihar elections of 2020 in between. Secularism, Peace, Social and Economic justice, threat of Majoritarianism, Authoritarian State, Casteism, Fascism, Pandemic and suffering of the marginalized and the poor are some of the themes that these essays cover. The vast ground covered in the book fully achieve the twin objectives which this book sets to achieve. As described in the Preface, the book aspires to share with the readers the perspective of the left and progressive South Asian diaspora in the US and Canada and celebrate the life of one of its founders and leading light of the progressive diaspora movement, Comrade Daya Varma. We learn about the INSAF Bulletin (the acronym for Justice in Hindi and Urdu), the digital mouthpiece of the progressive diaspora perspectives. INSAF Bulletin began in May 2002 under the inspirational editorship of Daya Varma and after Daya Varma’s passing in 2015, the mantle passed to Mubayi who had been closely associated with the Bulletin since 2004. The critical essays in this volume were published in this Bulletin over the years. The volume is important not only for its commentary on the five crucial years in the contemporary history of India, but it introduces us to a lesser-known side of the Indian diaspora in North America.

The book uncovers how in the recent years the two norms of Democracy that are often taken for granted i.e., mutual tolerance and institutional forbearance, have been thoroughly decimated and the very foundation of Indian nation has changed from secular nationalism to cultural nationalism.

Section 1 of the book primarily deals with the trajectory of India which the country is following through a reading of the contemporary society and polity. The titles of different essays in this section i.e., marching to a police state; creeping fascism; shape of things to come; malady of our time; and the nations trajectory – give away a lot about where the author thinks we are headed. The changing character of India is documented by looking at the response of the state in dealing with the CAA protest – the anti-Muslim minority legislation approved by the Parliament and the linked exercise of NRC and NPR. The chauvinistic response of the UP State against the brave women who came out to in CAA protest is evidence of this march towards becoming a police state. The assault on the students of Delhi’s Jamia Millia and Aligarh Muslim University and killing of over 20 protestors by UP cops is discussed as additional evidence. The continuity of political agenda between the law criminalizing triple talaq, the practice by which Muslim men could divorce his wife by uttering word talaq (divorce) three times and the approval of the J&K Reorganization Bill along with the two resolutions demolishing Article 370 and Article 35A are patterns pointing to the majoritarian character of creeping fascism in India. The crack down on the citizens of Kashmir following these revocations, the essays suggest, was even more brutal than on the CAA protestors, but the continuity of the political narrative connecting the two is also emphasized by the author. The direct and indirect defense of the lynch mob in the name of cow by the ruling party, and the claim that terrorist cannot be from the majority religion are two instances, that the author brings forth, by which the ruling party has reinforced its majoritarian nationalism in the recent years.

The tactics of intimidation and fear used against the political opponents, the representatives of minorities and other marginalized groups and the minority in general are the other important themes that are repeatedly highlighted in the essays. The essays discuss various ways in which this environment of fear has been established. This includes attacks on the individuals and institutions that ask critical questions on policy or seek accountability, harassment of upright journalists like Ravish Kumar, intimidation of the Dalits, vilification of those who stand for the rights of the Adivasi’s and Dalits, and criminalizing dissent especially during the Covid times. The essays also bring to our attention the handling by the State of what is known as Bhima-Koregaon case, where a group of human rights lawyers, academics, poets, and Adivasi rights activists have been arrested under the draconian preventive detention laws and incarcerated in overcrowded jails with delayed charge sheets and no indication of trial under ‘sensational’ charges including a plot to assassinate the Prime Minister. In the essays in this section, we see the author lamenting the withering autonomy of the Judiciary and the consolidation of executive’s control, contributing to strengthening the environment of fear.

A stimulating aspect of the essays is that they not only bring to our attention what is ailing in the Indian political reality, but many essays point to the light at the end of the dark tunnel. The author celebrates hope in essays like teetering between democracy and fascism highlighting the political participation of women in social and political movements, or the heroic resistance of the farmers to the farm laws.

The essays in the book are knitted together by foresight and clarity of principles in interpreting social reality around us. The framework is extremely helpful for the critical readers engaged with the question of social and political transformation. The essays provoke us to ask more questions. How for instance, the transformation from secular nationalism to cultural nationalism, and from mixed economy to market economy was built at the popular level and at the policy level? What made it a legitimate change and what justification sufficed? Afterall, the marginalization of the poor has been made possible through the same democratic processes which were previously proclaimed as the source of their emancipation. This poses the biggest challenge for the future of the Indian democracy and any project for transformation. In the past few years, we have witnessed the suffering of the poor. First it was the demonetization of the currency which had a ruinous effect on the working poor, then we witnessed the suffering of the migrant worker during the lockdown and the trauma of loss of life during the Covid-19 pandemic. We witnessed the working of a state which lack compassion and the suffering of the citizens who lack the power to seek accountability. We saw the government blaming the migrants for not being grateful to the state for preventing the spread of the contagion; and, we witnessed mostly in silence, the labour related legislative changes initiated during the Covid times delivering a key message that those who experienced hunger, unemployment, humiliation, indignity, and death during the lockdown were themselves responsible for their precarious existence. The attempt by the previous governments to “over-protect” them, they were told, made them more vulnerable. How the state becomes unaccountable to the suffering of the poor and marginalized and frees itself from any moral responsibility have changed crucially. What made this possible? The idea of a majoritarian India is accompanied by reconstruction of the citizen state relationship. The political and the economic are intertwined as many essays in the volume point to.

The essays in this book embody the spirit of betterment of people of India and the genre of writing – social commentary – makes these essays very lucid and accessible. The essays are substantive without being verbose, political without sermonizing and factual without getting lost in information, data, cross referencing, and footnotes. The book is a useful documentation of social history and a record of our times.

Atul Sood teaches at JNU, New Delhi