Following the outbreak of war in Ukraine, after some slight hesitancy Japan joined the European Union, the US, and other countries in both condemning Russia’s military invasion and placing strong economic sanctions on Russia. However, even while condemning Russia, a group of conservative politicians, headed by former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, saw an opportunity the pursue what has long been one of their major goals, not simply Japan’s rearmament with conventional weaponry but nuclear weapons as well.

On the surface, after having had two nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the closing days of WW II, Japan would appear to be the last country in the world seeking nuclear weapons. In fact, the Japanese people have shown in repeated public opinion polls that they are opposed to the possession of such weapons. This opposition is reinforced by Article Nine of the 1947 postwar Japanese Constitution that states: “Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

Nevertheless, as a condition for ending the Allied Occupation of Japan in 1952 the US imposed a military alliance popularly known as the US-Japan Security Treaty (Anpō-jōyaku). Then, in July 1954, a newly independent Japan created a Ground Self-Defense Force, Maritime Self-Defense Force, and Air Self-Defense Force. The Japanese government, ruled by conservatives for almost all of the postwar period, justified the rearming of Japan based on its creative interpretation of Article Nine. The government claimed that, despite the Constitution’s clearly stated provisions, the nation nevertheless possessed the inherent right to self-defense. All of this was done with the encouragement of, if not pressure from, the United States that was seeking an anti-communist Asian ally to join it in fighting the Cold War.

The main obstacle to Japan’s rearmament has been, and remains, the Japanese people, who even today remained traumatized by war and are now largely pacifist. Any amendments made to the postwar constitution require the consent of a majority of Japanese voters, a heretofore unlikely prospect as far as Article Nine is concerned. Hence, up to this point there has only been one way to accomplish Japan’s ongoing military buildup – incrementally and by stealth.

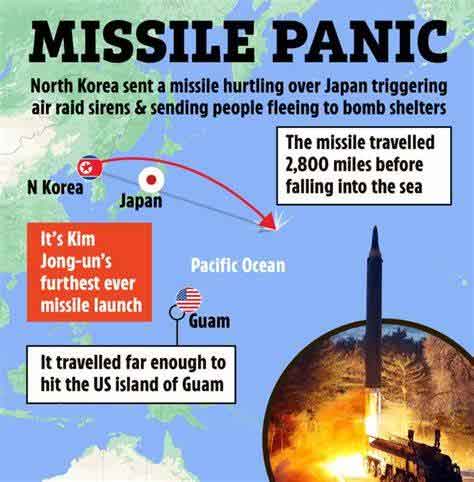

As but one example, in 1956, the Japanese government acted to allay the public’s fear of being dragged into a nuclear war as an ally of the US, by promulgating its “three non-nuclear principles” (hikaku sangensoku). These principles forbid Japan from 1) possession; 2) manufacture; and 3) introduction of nuclear weapons into its territory. However, the March 1, 2020 edition of the Japan Times reported that on Sunday, Abe said on a television program that Japan should begin discussions on seeking a nuclear sharing arrangement with the United States similar to NATO’s nuclear deterrence policy after Russia launched a military attack against Ukraine, a non-NATO member, last week.

“It is necessary to understand how the world’s security is maintained. We should not put a taboo on discussions about the reality we face,” said Abe, who heads the largest faction in the conservative, ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). China, which was savagely brutalized by Japan during WW II, reacted quickly, with the Foreign Ministry criticizing Abe’s remarks as a “dangerous trend haunted by the ghost of militarism.” In addition, not all members of other factions of the LDP agreed with Abe, including current Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo.

However, what neither Abe nor the Japanese government has ever publicly disclosed is that Japan is already sharing nuclear weapons with the US. I know from personal experience that, behind the scenes, the Japanese government has long given permission to the US to break the third of its three non-nuclear principles, i.e. the introduction of nuclear weapons into its territory.

In 1980 I was stationed on board the USS Knox, a destroyer homeported in Yokosuka, Japan. I say “stationed,” but I was actually a civilian college instructor employed to provide Japanese language and Asian history courses for sailors assigned to the Knox. The US Navy, in its wisdom, assigned me to room with the Knox’s nuclear weapons officer. Why nuclear weapons on a destroyer? Because the Knox was armed with anti-submarine ASROC missiles to which W44 nuclear depth charges could be attached.

Not only was there a steel door on the Knox with a large radiation mark on it, but an armed Marine stood guard in front of the door twenty four hours a day, while in port in Yokosuka or at sea. In addition, I personally saw the operation manual for these tactical nukes on the officer’s desk in our shared room as well as receipts for the weapons when they were loaded on board the ship in Guam, a US territory. The late, former US ambassador to Japan, Edwin Reischauer, later admitted that the introduction of nuclear weapons had been secretly agreed to by the Japanese government.

What Abe and his like-minded conservatives now hope to accomplish is to overcome the Japanese people’s deep-seated aversion to nuclear weapons, the first step of which is to “share” these weapons with the US. In the past, prior to the reversion of Okinawa to Japan in 1971, the US was able to store nuclear weapons at Kadena Air Force Base and other sites on that island. No doubt, especially in light of the current tension surrounding Taiwan, the US military would like to do so again. As for Japan, thanks to its multiple nuclear reactors producing electricity, it already has large stockpiles of plutonium that could quickly be reconfigured into nuclear weapons when the time came.

In a series of incremental steps, either little known or unknown to the Japanese public, Japan already possesses the fifth most powerful military in the world, ranking behind only the US, Russia, China and India. However, it still lacks one major component of big power status – nuclear weapons. If the Japanese people’s aversion to nuclear weapons remains so strong that Japan can’t have its own nuclear weapons, at least conservative politicians like Abe hope to be able to share them with the US. Will Abe and his conservative allies be successful in convincing the Japanese people to allow these weapons to be publicly stationed on its territory?

Time will tell. No doubt other countries, beginning with China, will also have something to say about this.

Brian Victoria, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies