Introduction

Symptomatic of the intensification of the US-led Cold War in the first two decades of the 21st century, the Russian war in Ukraine was a point of contention for military integration of former Soviet republics by the US and its Western European allies which welcomed and encouraged the conflict in 2022 in part to test the Atlantic Alliance’s solidarity against the background of a shifting world balance of power. Some scholars have argued that Russia’s war in Ukraine was similar to the US invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, or even direct and indirect Western military operations in Libya, Syria and Yemen, all former Western colonies. While the comparison is useful in so far as pointing out Western hypocrisy about selective wars and their consequences, especially considering the number of US military bases around the world and military operations from 1950 to the present, it is not historically valid to compare Russia’s war in Ukraine to the US-European wars in the Middle East.

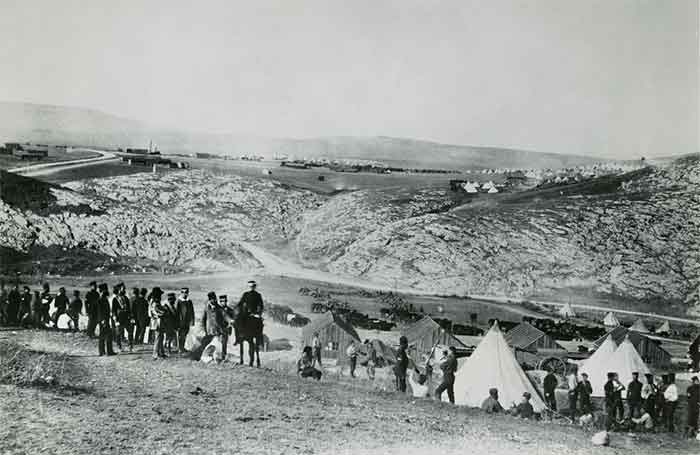

Russia’s war in Ukraine was part of a post-colonial “internal colonization” Russian policy in an attempt to recapture the regional balance of power and part of eroding global status lost in the dissolution of the USSR. From the perspective of the Western Powers using a periphery state within Russian historic zone of influence, the war in Ukraine was somewhat analogous to South Africa’s Boer War (October 1899-May 1902). This is because the early 21st century multi-polar world order, in some respects, resembles the Age of Imperialism (1870-1914).

Just as the Boer War was in essence a conflict between Germany supporting the Boers, (South African of Dutch and German settlers of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State) against British quest for colonial hegemony, similarly, the Russian-Ukraine conflict is a 21st century version of a 19th century war of imperialism. One of the most significant wars of imperialism, the Boer War motivated British scholar John Hobson to write a book entitled Imperialism, which influenced Rosa Luxemburg and V. I. Lenin’s views of imperialism’s global impact on social and international relations. Hobson warned that South Africa’s war of imperialism was a precursor to a major conflict between the Great Powers. The outbreak of WWI proved his point.

From ancient times to the present, no government has ever gone to war expecting major loses in a long-lasting conflict that would broaden the field of players and unleash destruction on a massive scale. More than any other domain, war brings out delusional optimism on the part of policy planners and military enthusiasts who behave like drug-addicted gamblers about to taste the glory of victory without cost.

Consistent with its post-Soviet policy of integrating as many countries surrounding Russia as possible under NATO’s aegis, the US and EU declared an “Open Door Policy”; a remnant from the Spanish-American war of imperialism under presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt pertaining to China. The Open Door Policy was especially important after the Chinese Boxers Rebellion (1899-1901) as it led to Japan’s imperialist designs in Manchuria and China’s financial dependence on Europe.

The thinly disguised US-NATO expansionist policy in Eastern Europe and Eurasia after 1990 not only upset the regional balance of power and resulted in preventable conflict, it further became the pretext for asserting the new “Open Door Policy” in Asia where China is a rival that the Trans-Atlantic alliance is not in the position to threaten with sanctions unless it is prepared for a very deep and long global depression. Considering that China helped to mitigate the effects of the Global recession of 2008, and that its GDP measured in PPP terms in 2021 exceeded that of the US by five trillion dollars, confronting China in the same manner as Russia would be an indication that Western policymakers are bent on self-destruction, willing to take down the entire world. As Dutch scholar Johan Huizinga argued upon observing how elites become exceedingly sadistic in their desperation to retain their privileged positions in society after WWI, such a scenario is not at all unrealistic in the 21st century.

Although the mutually-beneficial option before the NATO bloc and Russia was diplomacy before Russia started the war, the US was publishing intelligence reports, over Ukraine’s objections, instead of either referring the matter to the UN Security Council or engaging in a realistic bilateral diplomatic solution. History has shown that diplomacy to end a war can take the wrong turn and conflict can make an inevitable a return to hostilities. This was the case with the Paris Peace Conference that ended WWI only to leave it unfinished and allow for its continuation in WWII. Because it was not the vanquished but the victors who are responsible for the detrimental flaws in the peace treaty, one must keep in mind that the parties holding the leverage at the negotiating table enjoy a far greater burden to ensure lasting peace and stability.

Historical Antecedents

Without going back to the 9th century to trace the origins of the Russia-Ukrainian conflict, a point of departure for this brief essay is the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) which ended hostilities between Imperial Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to which Ukraine’s “right bank” belonged, while Russia took the “left bank” as part of its “internal colonization” strategy. The Scientific Revolution and mercantile capitalism in 17th century Western Europe, especially during Peter the Great’s reign (1682-1725), reflected and encouraged disparate elements from Western Ukraine looking to the West vs. those in the East and rural areas with an affinity toward Moscow.

Although Ukrainian nationalists looked to the West more as a means to assert their autonomy but also to emulate modern Europe rather than Medieval Russia, the issue remained very much alive throughout the Tsarist era. Ukraine was always part of Imperial Russia’s long-standing policy of “internal colonization”; namely, internal conquest from the Pacific to the Atlantic and from the Black Sea to the Bering Sea. Unlike Western Europe and the US expanding beyond their continental borders seizing territory and spheres of influence in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, Russia expanded within the Eurasian continent.

In the aftermath of the Byzantine Empire’s fall to Ottoman Turks (1453), Russian Tsars viewed their role as the rightful successor to the Byzantine Empire and patron-protectors of Orthodox subjects inside and outside Russian boundaries. Putin could not make such a claim in Orthodox Christian Ukraine, but he laid claim to “cultural protection” of the Russian ethnic minority and the strategically important Crimea.

The Crimean War of 1853-1856 which Russia lost to Britain and France brought into focus the geopolitical significance of Ukraine’s strategic position and the need for access to the Mediterranean. Tsar Nicholas I (1825-1855) used the pretext of Russian “protection for Orthodox subjects” of the Ottoman Empire to go to war against the Ottoman Empire which was in essence under the semi-colonial control of Western Europe. Although the European Great Powers easily prevailed in the Crimean War, they recognized that it was not in their interest to deny Russia access to the Black Sea and punish it to the degree that destabilization would ensue with consequences for European security; a lesson that US-EU Cold Warriors neglected in their approach to Russia’s relationship with Ukraine in the 21st century.

At the Treaty of Paris in 1856, the British and the French governments set limitations not only on Russian power, but on their own military ambitions in exchange for harmony in the European balance of power. This was a lesson learned from the Metternichian Congress of Vienna after the Napoleonic Wars (1814-15) and a mode of operation which Otto von Bismarck also followed both as Prussian foreign minister and German Chancellor. Setting limits on one’s own power became a major East-West Cold War issue because of the nuclear arms race and the MAD – mutual assured destruction – doctrine of the 1960s. From the end of the Cold War to the present, the US and Western NATO partners have dogmatically refused to set limits on Western expansionism.

The uneasy Moscow-Kyiv relationship continued once Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution broke out, followed by the Russian civil war and foreign invasion (1918-20) in which many Ukrainians sided with the Tsarists against Leon Trotsky’s Red Army. US president Woodrow Wilson quickly realized that Japan and European countries involved in the Russian Civil War entertained territorial ambitions. In essence, they were using the Bolshevik Revolution to pursue imperialist ambitions. This is relevant today because of the role of the West in 2022 in Ukraine which goes beyond the strategic balance of power as NATO has been moving East since the 1990s.

Unlike Lenin who was patient with reluctant Ukrainians to accept the Soviet system of centralization and collectivization, Stalin, who was Georgian and eager to prove more Russian than the Russians surrounding him, adopted harsh measures against Ukrainian nationalists. The most glaring example of this was the famine of 1932-33 when Stalin allowed several million Ukrainians to die of starvation as political punishment for their resistance of collectivization. This tragedy left deep and long memories in the Ukrainian population, some of whom sided with the invading Third Reich army against the Soviet Union during WWII once Germany installed, Reichskommissariat Ukraine which was the occupied government.

After Stalin’s death, the political climate between Ukraine and Moscow improved. Ukraine was more developed than the rest of the Soviet republics, and relatively rich in agricultural and raw materials, as well as a supplier of value-added products for the entire Soviet market. Like the rest of the non-Russian republics awaiting the Soviet Union’s disintegration during the presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev, Ukraine was even more so because of its uneasy history and ambitions to achieve greatness under Western integration.

When thousands of Ukrainian nationalists organized a human chain for independence in January 1990, it was the beginning of national sovereignty. In August 1991 they were rewarded with the formation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic which reaffirmed national sovereignty after refusing to sign a new union treaty with Moscow in October 1990. During the Yeltsin decade, the Russian Federation was at its nadir. Meanwhile, the US and its Western European partners swiftly integrated a number of former Soviet republics into the Western orbit, advising Yeltsin’s Russian Federation that neoliberalism, globalization, and aggressive privatization was the path to Western dreams of riches and democracy.

From Economic Crisis to War

The end of the USSR left the Russian Federation very weak, not only in comparison to the Communist-era but to Tsarist Russia after the Crimean War when it became necessary for Tsar Alexander II (1855-1881). Reduced from a military superpower with East European satellites to merely a nuclear power with GDP lower than Italy’s and a bit higher than Spain’s, Russia under former Soviet bureaucrats and KGB officers like Putin created a corrupt Kremlin-linked oligarchic capitalist system unable to compete in the international market, and relying heavily on fossil fuels and primary sector exports. In many respects, Russia resembled a Third World monocultural economy. In the name of neoliberal privatization, Kremlin-linked oligarchs raided the country’s public wealth, exporting capital and purchasing everything from luxury estates in major world capitals to luxury yachts in exchange for loyalty to the Kremlin. Ranking 70th in GDP per capita income in the world, Russia’s socioeconomic inequality and rampant corruption has been taking place under a regime claiming to be democratic but is in essence authoritarian.

Heavily relying on fossil fuel exports, Russia hitched itself to neighboring China’s development and geopolitical interests out of necessity without many alternatives in the global arena, while China has been using Russia for its raw material exports and geopolitical maneuvering against the declining West. The two countries’ respective geopolitical interests converged in so far as both faced a predatory trans-Atlantic block using not only its privileged global role in trade and reserve currency domains, but aggressively applying sanctions as a form of economic warfare. In the first two decades of the 21st century, Russia was more on the defensive than during the Romanov dynasty’s last decades or even the Soviet Union’s declining years. Nevertheless, the myth of a paternalistic mother Russia protecting the subservient “Little Russians”, which includes Ukraine, remained part of the Kremlin’s political culture.

For its part, Ukraine became integrated under the global neoliberal transformation model and experienced some growth until the US-based Great Recession of 2007-08 when the economy contracted. Just as Russia’s sociopolitical relations were based on a government-linked oligarchy, the same was the case in Ukraine where capitalists were linked primarily to Western interests, although China became a major trading partner after 2008. By the time of the 2010 presidential election, former Orange Revolution (November 2004) allies Viktor Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko were on opposing camps, thereby prompting pro-Moscow Viktor Yanukovych to win and setting the stage for the intense rivalry about Ukraine holding the balance of power.

In the ‘Revolution of Dignity’, Yanukovych was removed for rejecting the Ukrainian-European Association Agreement in November 2013; a move that made Moscow uneasy as it viewed Ukraine part of its sphere of influence and potentially destabilizing the delicate balance of power. In February 2014, after two months of protests and street fights between police and the crowd, parliament ousted the pro-Russia president who moved to Russia. In retaliation, Moscow annexed Crimea in March 2014. A month later, pro-Russian elements in Donetsk and Lugansk proclaimed autonomy with Moscow’s blessing and support.

Because elements from the far right were involved in many sectors of Ukrainian society, from local politicians to the police and military, Moscow exploited the situation to argue that it was merely protecting the democratic rights of the Russian-speakers and pro-Russian Ukrainians. Although Putin used “de-Nazification” to justify the invasion, the neo-Nazi issue was a thinly-veiled pretext because those elements were in Ukraine since the early 1990s. Ironically, Ukrainian white supremacists inside the armed forces, the police, government bureaucracy, and in the heart of the economy are as adamantly against popular sovereignty as the Kremlin. Western governments and media rarely focused on neo-Nazi Ukrainians, just as they rarely mentioned that NATO cooperation with authoritarian East European governments was hardly the road to ‘democracy’ as President Biden and EU leaders proclaimed.

Taking advantage of China’s global ascendancy and relative US decline, Russia was leveraging its foreign policy by forging closer ties with Iran, India, Pakistan, and Turkey. Predictably, Russia’s role in Syria emboldened Putin, as it was a resounding defeat for the US-Saudi-Israeli alliance behind a regime-change effort that only strengthened Iran and Russia in the regional balance of power. Just as important, during his presidency, Trump questioned the value of NATO in any role other than buying US weapons. He also used NATO as leverage to sell LNG to Europe at far higher prices than what Russia was charging. Moscow’s perception of a fragile Atlantic alliance, ambiguous geopolitical and economic interests, and heavy EU reliance on Russian energy reinforced Putin’s illusions about the lengths to which Western militarists would go, regardless of economic consequences to their economies.

As the Russian war intensified, global media outlets representing their respective governments’ policy unleashed an “information war”, partly to justify the reverberations of Western sanctions on the world economy. With the exception of a few faint voices in Arab, Pakistani, Indian, African, and a few other news outlets around the world, journalistic coverage has been one-sided. What upset many non-white non-Christians world-wide is the fact that Western governments and media presented the war from the victims’ perspective because Ukrainians are white and Christian, not dark-skinned and/or Muslim like Africans and the Middle Easterners.

At the same time, most Western reporters and analysts have been clamoring for a military solution, despite all which it entails for the Ukrainian people, but also for the world economy. Provocative statements from Biden and top NATO leaders and the blatant double-standards regarding war crimes in Ukraine vs. war crimes in the Middle East have only added fuel to the fire about the new Cold War. Beyond moral double-standards, the Russian and Western media’s quest to indoctrinate the public has a price tag for the world. Militarization on a world scale, lower living standards amid rising cost of living in all countries, and the dreaded prospect of a “limited nuclear war” were unsettling. Both Russia and the US have enough warheads to destroy each other dozens of times over. The Kremlin made no secret that it would use nuclear weapons, if it perceives there is a real threat to its “national security”, a vaguely defined concept.

While the possibility for any use of nukes was never very high, US-Russian relations reached the lowest level since the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962; so low, that Biden’s comments about regime change reflected the mindset of a Cold War politician dreaming of the Pax Americana in the 1950s. All along, Moscow continued destroying Ukraine, while insisting that bilateral peace negotiations notwithstanding, “One way or another, sooner or later we (Russia and US) will have to talk about the issues of strategic stability, security and so on, in other words, those issues that only we can and should discuss.”

The general public may find it curious that NATO countries, including non-NATO Ukraine, were actually selling weapons to Russia after Putin annexed Crimea in 1914. Wall Street investments were part of the defense industries involved. Weapons sales cannot take place without the full knowledge and approval of the host government, including the US whose investors in defense companies were making money. The hypocrisy of Western sanctions against Russia reached new heights beyond what took place after Crimea’s annexation in 2014, considering that Western institutions laundered Russian oligarch money and shielded their operations behind dummy companies with the full knowledge of both the US Treasury and Justice departments.

In order to win over India, which refused to go along with the US and NATO on sanctions, US defense contractors were trying to sell weapons to India which historically has been buying mostly from Russia and Europe. Indicative that capitalist enterprises have also been driving the war, while governments have been crying out for Western solidarity against Russia, Western companies have been making massive profits because of Russia’s war. They have been selling weapons not only to allies but also to the friends of NATO’s enemies. Western defense corporations’ profits in the first quarter of 2022 rose 25% because of the war, the exact percentage of Ukrainians displaced in February and March 2022.

On 3 March 2022, AXIOS published an article entitled: “The dollar remains the West’s ace in the hole.” About 20 percent of the world GDP in nominal value, US economic strength rests in the fact that 60 percent of the foreign exchange reserves in central banks are in dollars. One US goal in sanctioning Russia was to strengthen that position. Instead, a number of wealthy countries have been transitioning away from the dollar as a reserve currency. After Saudi Arabia’s decision to bypass the dollar in oil transactions, India opted for the same strategy in a diplomatic blow to the US sanctions policy and to the dollar as a reserve currency. India’s move was serious because of the size of its economy, combined with its refusal to go along with the US sanctions policy. Even more serious, China’s role in undercutting Western sanctions by solidifying its ties with Russia.

China’s Role

In a joint session of Congress on 11 September 1990, President George H.W. Bush proclaimed the birth of the “New World Order”. In outlining US post-Cold War goals and modalities, Bush promised to usher in a new era of justice, freedom and democracy for the entire world. Putting aside delivering democracy to the world, the US did not deliver on such promises to its own citizens concerned about voting rights, democracy, freedom, and social justice. Unlike Russia interested in its national security and regional balance of power and the US desperately trying to retain the glory of 1950s Pax Americana, China has a more complex global role. Geopolitically, Beijing’s interests are with Moscow, but economically with the entire world. Top leaders of the Chinese Communist Party have not concealed their assessment of the US as a declining empire desperately using sanctions and its military presence in two-thirds of the world’s countries as leverage to retain power. While the war in Ukraine represented an economic setback for China, it also presented the opportunity to observe how the US and its junior partners would behave. Beijing’s interest was also to determine how the West would behave in Ukraine so that Beijing could determine a scenario pertaining to the Taiwan-South China Sea areas of contention between China and the US.

Because China views the US as having an interest in destabilization, not just in the Middle East through proxies like Israel and Saudi Arabia, but also in South China Sea, Eastern Europe, and the Trans-Caucasus region, Beijing’s balancing act goes to the heart of how it wanted to manage crises with minimal damage to its own interests in the world economy. One consequence from Russia’s war in Ukraine was a stronger yuan as a reserve currency. Although US government and independent analysts were actually expecting a massive international rush to the dollar as a safe hard currency, a downgrade in the US dollar’s dominance is inevitable as the US will be borrowing more to spend on defense as it refuses to abandon military Keynesian policies and corporate welfare as part of the neoliberal model.

Beijing’s top leadership was concerned about the duration and scope of the Russian war. This was especially after the US announced that it was considering “secondary sanctions” which meant Asian countries would either go along with US-backed sanctions against Russia or face US trade and investment retaliation. Because China’s leverage is the world economy, its main concern has been how to manage the Russia-Ukraine-US-NATO crisis with minimal damage to its long-term interests. The longer the war continued, the worst for China to find alternate corridors for its Belt and Road Initiative, bypassing Iran, Russia, and Ukraine to reach Europe’s lucrative markets. China’s other concern was that the US has been using the war to gain increasing market share in Europe’s energy market which is not in China’s interest as it entails bloc trading and economic nationalism undercutting globalization. It was also not in China’s interest for her trading partners around the world to spend more on defense as the US has been urging to bolster its own defense industries. Such a scenario undermines Chinese economic growth prospects, though this too is a temporary situation.

Whereas Russia is not in the position to influence the global balance of power and world economy, China and the US are at the core of this war more than it appears on the surface. Geopolitical decisions both countries make, how they decide to handle all sides of the conflict which impacts the entire world, and how they plan to balance East against West to minimize US-NATO destabilization provocations and maximize global market growth will impact the lives of billions of peoples’ living standards. Presidents Obama, Trump and Biden attempted to contain China through various mechanisms from tariffs to sanctions and military exercises in the South China Sea. These were manifestations of US economic decline measured against China’s ascendancy.

Empires of the past, including, the Persian, Athenian, Roman, Spanish, and British spent themselves into oblivion by assuming that military not economic power is the path to riches and glory. Although the goal was to secure more riches from others through military campaigns, the cost of perpetual conflict and high military spending ultimately bankrupted them. The USSR spent itself out of existence because it was obsessed with the military dimension of its “superpower” status, to the neglect of the civilian economy. Relying on military Keynesianism, the US from the Truman administration to the present has been on the same path as all failed empires. It defies logic how a two-front US containment policy toward Russia and China can possibly lead to anything other than hastened decline and serious internal sociopolitical problems.

Kissinger’s advice that striving to cultivate better relations with both Moscow and Beijing than they entertain for each other was based on the realistic assessment rather than confronting Russia and China simultaneously which would be a prescription to disaster. Even more significant, the warnings of John Hobson, Joseph Schumpeter and John Maynard Keynes about the inherent contradictions of capitalism and its imperialist nature are as applicable in the 21st century as they were in the early 20th century. Just as capital accumulation on a world scale resulting in underconsumption led to more aggressive imperialist adventures from the late 19th century to the outbreak of WWI, the world is confronting similar conditions under the neoliberal transformation model of the last four decades which kept the Cold War alive in spite of the collapse of the Communist bloc.

Jon V. Kofas, Ph.D. – Retired university professor of history – author of ten academic books and two dozens scholarly articles. Specializing in International Political economy, Kofas has taught courses and written on US diplomatic history, and the roles of the World Bank and IMF in the world.