There are some fascinating similarities between the Crimean War of the 1850s and the Ukraine War of 2022. According to Norman Rich, author of “The Crimean War” its main purpose was the containment of an expanding Russia as European powers had become fearful of Russia’s extension of power under Tsarist rule. One of the questions Rich addressed was why peace efforts failed at the very time that European powers were opposed to another war.

As a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the major European powers decided that the “primary objective of their diplomacy must be the preservation of international peace and stability” Their collaboration became known as the “Concert of Europe” which supported peace efforts for the following four decades. But from October, 1853 to February, 1856 a war was fought by the British, French and Ottoman Turks against Russia. It was a blood drenched war that brought such luminaries as Florence Nightingale and Leo Tolstoy to the world’s attentions and made famous Tennyson’s poem: “The Charge of the Light Brigade”, adapted from Dublin born, William Howard Russell’s article about this disastrous charge that resulted in the death of 300 out of 600 men. Besides W.H. Russell another Irish war correspondent: J.C. Mc Coan, wrote articles about the “great confusion of purpose” and the “incompetent international butchery” that took place in the Crimea.

Sixty thousand British, French and Ottoman Turks died in the ensuing three-year conflict, while up to 500,000 Russians lost their lives, many due to cholera, typhus, dysentery and malaria. It was in this harsh medical climate that Florence Nightingale gained widespread attention for setting up a hospital while bringing a number of trained nurses, including a substantial contingent of “Sisters of Mercy” from Ireland. They were there to heal wounded soldiers by establishing strict rules for cleanliness at a time when germ theory had not been understood. Before the nurses arrived 16,000 British soldiers died and, after the establishment of the hospital, only 2000. Nightingale noted in her journals that there was an 80% reduction of mortality among wounded soldiers under the care of her nurses. Her efforts resulted in widespread recognition of the need for professionally trained nurses in caring for injured soldiers.

A young Russian officer, Leo Tolstoy, served in combat in Crimea and became embittered by the suffering and death of young men. Based on his experiences Tolstoy wrote: “Tales of Sebastopol” and later his famous book: “War and Peace” and still later numerous books and articles on ”Nonviolence” which inspired Mohandas Gandhi to found “Tolstoy Farm”, his first ashram in South Africa.

According to some historians, the cause of the 19th century Crimean War was that France and Britain had become fearful of Russia’s attempt to expand its influence into the Ottoman Turkish Empire. Russia’s vast territories stretched across the continent to Siberia and Alaska and coastal North America. The Russian Tsar, Nicholas II believed the Ottoman Empire was in imminent danger of collapse and expressed his intention to protect the Orthodox Churches and the Holy Places of Jerusalem which were under the Sultan’s rule. The Tsar’s diplomatic mission to Constantinople in 1852, led by Prince Menshikov, had been told “to demand a formal Turkish Guarantee of existing rights and privileges of the Orthodox Church. The British Ambassador to the Ottoman Court, Stratford Canning, was a “mediator and mentor to the Ottoman Court” and advised against any accommodation with the Tsar. He was convinced that the Russian demands would allow the Russians to gain control of the Ottoman Empire.

Reinforcing this view was Lord John Russell who stated that: “He [the Tsar] must be resisted in any way possible”. Other aristocrats such as the Duke of Argyll wrote that “the seating of the Russian Empire on the throne of Constantinople would give Russia an overbearing weight in Europe”. Lord Palmerston, who became Prime Minister had a desire to enhance British prestige”, and, as a result, became a major factor in the drama that ignited the conflict with Russia.

The Ottoman government agreed with Britain and France that there was a need to mount a campaign against Russia. Attempts at brokering a peace were blocked several times by British leaders, while the Habsburg Empire with its base in Austria, supported peace efforts. Prince Metternich, a proponent of peace, warned against a “European war provoked by Oriental causes” and expressed the “need to maintain treaties” since “we are called to the task of restoring peace”. Yet there was a problem with the vacillating nature of Tsar Nicholas 1 and his “sudden hatreds [and] exaggerated sense of honor and pride”, mixed with “severe bouts of depression”.

In England the issues came to a head in December 1852, after Napoleon III established a new imperial government in a coup d’etat against the Second Republic. He sent an ambassador to the Ottoman Empire with instructions to assert France’s right to protect Christian sites in Jerusalem and the Holy Land. The Ottoman Empire agreed to this condition. A Four Point Peace Agreement was put forward in 1854 to cease hostilities but they were repudiated by the Tsar unless guaranteed protection was given to the Holy Places and the Orthodox churches.

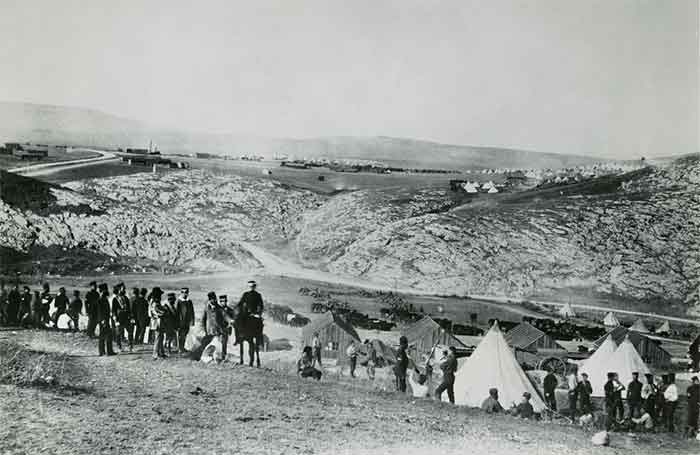

Although the Crimean war ended in the winter of 1856 peace efforts could have prevented this costly war. Instead, what took place resulted in the suffering and death of 560,000 young men on both sides of that war. Irish soldiers made up around 30–35 per cent of the British army in 1854, and it is estimated that over 30,000 Irish soldiers served in the Crimea, a number of them casualties of the war. Since each Irish regiment allowed a small number of wives to accompany their husbands to the Crimea, these women came to wash and cook, and following each battle, helped to care for the wounded.

The crippling of Russia’s power in the Near East was imperative to Britain and France. The British war party undermined peace proposals that could have ended the war much sooner due to their desire for more concessions from Russia, including the obliteration of Sebastopol and the reduction of Russia’s Black Sea fleet. Tsar Nicholas I died in March,1855, worn out and remorseful after his failed efforts to avoid war. Nicholas believed he had tried to “honestly” negotiate with Britain on the partition of the Ottoman Empire, and indicated his willingness to make concessions. But all efforts in this regard, failed. Nicholas’ son, Alexander II, was willing to sue for peace, but such “a peace had to be on honorable terms”. The earlier Vienna Peace Conference had failed in June, 1855 with the chief negotiator for Austria being Sir Karl Von Buol, who noted that the “uncompromising attitude of the western powers wanted to force a decision on the battlefield.”

Lord Palmerston’s “grandiose plans” were to dismember the Russian Empire so that it would not “dominate trade from the Baltic to the Mediterranean”. After the capture of Sebastopol in September, 1855 and the withdrawal of all Russian forces from the city, Tsar Alexander II defiantly declared that “Sebastopol is not Moscow and the Crimea is not Russia”. Yet Lord Palmerston stated that the Treaty we propose would be “…to confine the future of Russia within her present circumference” and insisted that “Russia has not been beaten enough to make peace possible at the present moment

A Four Point Proposal by Austria was put forward by their representative, Karl Von Buol, as an “ultimatum to Russia” although he noted that “the terms must be moderate enough to be acceptable”. Austria was convinced that it needed to “end the war regardless of the political cost”. The proposal demanded that the Black Sea be open to all commerce and the River Danube be removed from Russia’s control. The Four Points were agreed to by all sides and the war ended. The great cost of lives lost and deep seated resentments continued to simmer in Russia against the European powers, although there were some positive results. The horrific loss of young men, as well as a loss of prestige, compelled Russia to re-structure and upgrade their judicial system and military and, most importantly, Tsar Alexander gave freedom to the serfs.

Just as the concern for Holy Places in the Ottoman Empire was a motive for the Crimean War, so too are religious motives mixed with political motives in Ukraine and Russia. Patriarch Kirril, head of the Russian Orthodox Church in Moscow, has become upset at the Ukrainian Orthodox Church’s independence and wants to re-assert control of Ukraine’s Orthodox churches. Over half of the churches of the Ukraine are still affiliated with Moscow while less than half joined the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Of the 800 or so churches affiliated with Moscow, 400 Russian Orthodox priests appealed to the “Council of Primates of the Ancient Eastern Churches” claiming that Patriarch Kirril was preaching the “doctrine of the Russian World”. The Orthodox priests were upset at the Patriarch’s staunch support of Vladimir Putin during his harsh prosecution of the war in Ukraine.

In our present year, 2022, Vladimir Putin, has Tsarist aspirations and asserts Russia’s intention to re-create a region of influence so as to prevent the expansion of NATO. The Crimean Peninsula has been under the flag of Ukraine from 1954 to 2014 after which it was annexed by Russia. But despite this annexation Ukraine continues to refer to Crimea as the “Temporary occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sebastopol by Russia”.

If the Ukraine War follows the same destructive path as the original Crimean War, the consequences of which resulted in a fragmentation of the Ottoman Empire, and a Europe that became more divided, the most likely result will be a society with deep-seated resentments that may take decades to achieve some degree of reconciliation toward those who took part in the violent invasion of their country.

The Historian Tacitus, while discussing Agricola’s conquest of Celtic Britain, related an insightful aphorism: “we hate most those we harm the most” in reference to the Roman policy of compelling servitude upon the conquered. This too could be said of Vladimir Putin’s legacy: that hatred and vindictiveness has been growing in opposition to his plans for conquest, which have been thwarted by Ukrainian resistance and their profound need for independence. Putin’s attempts to reawaken the ghosts of Empire have become more strangely improbable at a time that Russia’s economy continues to shrink as a result of sanctions, an economy that is barely on a par with Canada’s. It is unlikely that in the future Russia will be able to support a military that is comparable to nations with economies ten to twenty times larger.

Hugh J. Curran has been teaching in “Peace and Reconciliation Studies” at the University of Maine for the past 20 years.