Gone are the days when menstruation, one of our country’s major taboos, was spoken with a ‘hush’ or a ‘shh’ in our society. With films like ‘Padman’, ‘Phullu’, ‘Period. End of Sentence’, the sanitary pads have suddenly gone mainstream. But let’s not forget the fact the country still has limited acceptance with menstrual cups and the discussion around sustainable menstrual products due to its obsession with virginity and sexuality. Let’s break it into different phases.

The first step in the conversation on sustainable menstruation is raising awareness. When I received my sanitary napkin in 2006, I was overjoyed because I could finally use the white product that I had seen on television. However, recurrent clogs in the toilet pipes caused my mother to question the manner in which I dispose it. My thirteen-year-old self had no idea that her monthly use of sanitary napkins was clogging toilets. The fact that the sewer drain, once opened, remained filled with pads with no change in its structure even years after it was flushed out, prompted me to begin discussing the upcoming catastrophe with my friends.

Using resources rightly without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs is the tag behind sustainable development. It’s said that a single woman can produce up to 200kg of menstrual waste in her lifetime. These non-biodegradable material stays in the environment for around 400-500 years. In rural India, often the disposal is through burning, burying or throwing into latrines, resulting in widespread environmental pollution. It is at this time, we shall discuss what level of awareness is present in the contemporary scenario on sustainable menstrual products. Organic tampons and pads are significantly less popular than their non-organic counterparts, although identical both physically and in their manner of use. The amount of plastic present in the latter is unaware to majority of the communities. In many circumstances, despite consumers’ understanding of the negative impacts of menstrual waste on the environment, a change in their practice is unlikely. They reject sustainable menstrual products (SMP) owing to a lack of choice and comfort in maintaining stability, hence accepting menstruating women’s taboo position.

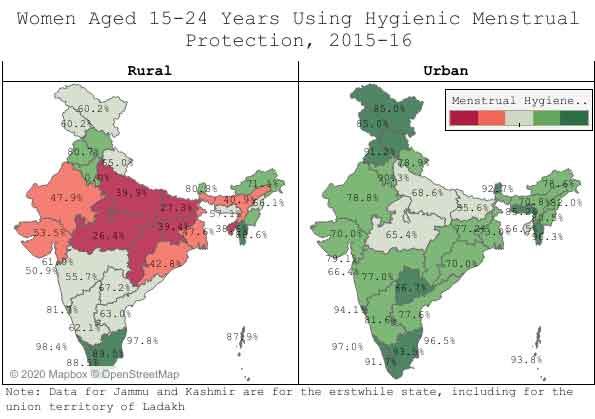

Let’s speak about the affordability of menstrual products now. As they cannot afford to its monthly expense, many women and girls resort to less sanitary methods during their menstrual cycle. For mothers in rural India, spending 50 rupees a month on sanitary pads is a luxury when they can’t even afford milk for their children. The covid-19 issue exacerbates the period’s poverty. The Indian government’s decision to make tampons and sanitary napkins tax-free may come as a huge relief to millions of menstruating women who do not have access to a safe period. However, concerns have arisen about companies being forced to use cheaper raw materials in order to cut costs, which can cause increased damage to environment.

Access to hygienic menstruation products has become a faraway dream for women from low-income families. Reusable items, such as cotton pads, which are commonly used in these families, are sometimes not adequately sterilised, which promotes reproductive infections. Cloth pads are becoming increasingly popular, but they do not last long since they are difficult to wash, thus they are thrown after usage. Social taboos also hinder women from using sterilised water to wash and dry these pads. The Covid 19-induced lockdown has limited women’s access to safe menstrual hygiene. Due to a lack of access to pads, they were forced to use cloths throughout their periods. As pads are limited (8 pads in a package costing roughly 40 rupees), girls are forced to limit their water intake so they do not have to replace pads frequently. This can lead to serious medical conditions.

Towards sustainable menstruation

The lack of awareness, affordability, and accessibility results in the poor management of menstrual products after use. Toxic contaminants in sanitary pads degrade soil structure and fertility, as well as pollute the water table. Due to the increased chemicals used in making the pads ‘cottony soft’ with a ‘pleasant aroma,’ municipal waste collectors are forced to segregate them manually. Incineration is also ineffective since contaminants persist after the treatment. As a result, one cannot help but consider the long-term solution for healthy menstrual hygiene for both oneself and the environment. Some of which include biodegradable sanitary pads, menstrual cups and washable cloth pads.

In October 2018, a group of Kerala Higher Secondary Girls created a sanitary pad made of water hyacinth, a plant that damages aquatic life in rivers and ponds. This three-rupee napkin absorbs 12 times the amount of water than a typical sanitary pad. Saathi’s banana fibre pads are another SMP that can be decomposed in a landfill in three months.

Another SMP is reusable menstruation cups, which are made of silicon or latex rubber and cost around 200-300rs. They can hold more blood than sanitary pads and are reusable after 10 years, minimising waste production. However, the stigma associated with vaginal insertion, as well as growing market cost, gives limited acceptance in rural areas.

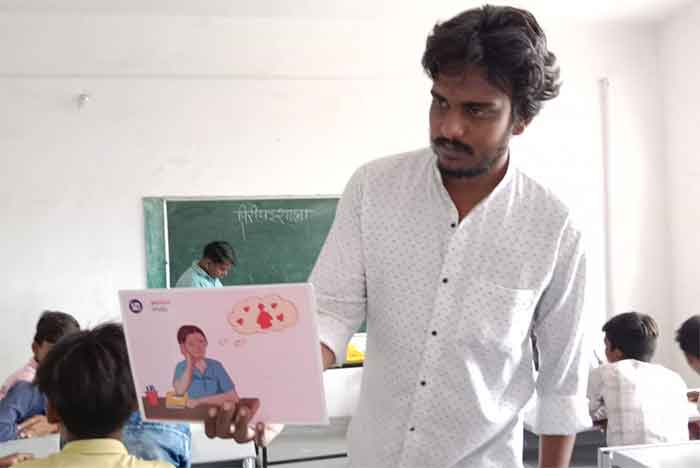

As a result, the development of SMPs may be facilitated by breaking down barriers and raising awareness. The government’s sanitation awareness can help to balance the demand and supply debates. A thorough understanding of the pros and cons of various menstrual hygiene products leads to better health seeking behaviour in these communities. Education interventions, as well as community activities and social media efforts to normalise period talk, can assist to reduce the stigma associated with menstruation. Sustainable menstruation will be the subject of a private-public cooperation. Along with sex education and reproductive discussions, it’s time to discuss the usage and correct disposal of menstruation products. As American abolitionist and author Harriet Beecher Stowe remarked, ‘A woman’s health is her capital.”

Bulbul Prakash is pursuing M.Phil in Diplomacy and Disarmament from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India