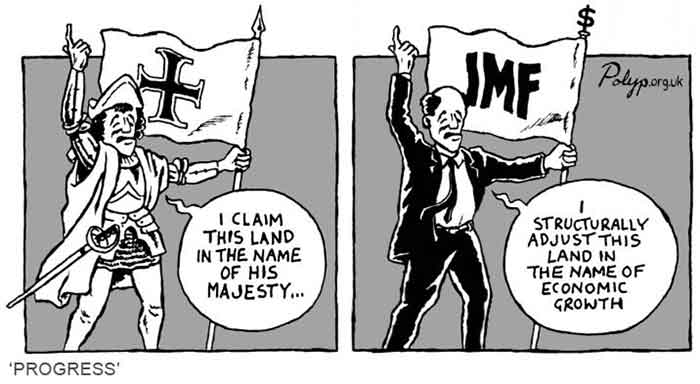

While the meaning and practice of “colonialism” hardly needs to be described, the meaning of “neo-colonialism” is far less understood. This is because neo-colonialism is much less evident to the eye, unless, that is, one cares to look for it. Let us begin our search with the dictionary definition of the term. Merriam-Webster defines “neo-colonialism” as: “The economic and political policies by which a great power indirectly maintains or extends its influence over other areas or people.” Here the operative word is ‘indirectly’ though I suggest that instead of ‘influence’ a more accurate definition is: ‘control’, i.e. control over other areas or people including control of their natural resources and labor.

In the ‘bad-old days’, powerful countries, initially in Europe and later, both the US and Japan, had their own colonies over which they ruled directly, placing their own nationals in charge of the local populations and, should the colonized raise up against them, using their own militaries to apprehend, terrorize and kill those who resisted. Although the colonial powers were not always successful in their colonizing efforts, e.g. the American War of Independence, the system whereby large areas of South America, Africa and Asia remained colonial possessions of mostly Western powers lasted until the end of WW II.

Neo-colonialism, with its ‘window-dressing’ of rulers selected from among the ruled, rather than colonial Governor Generals, et al., may appear on the surface to be more benign than outright colonialism. However, the revised system of rule still operates on the basis of the unhindered acquisition of enormous wealth by the few. Taxes or regulations sufficient to break the cycle of wealth acquired by the few remain unthinkable. Neo-colonialists require the countries they control to pledge unquestioning allegiance to capitalism, something they often euphemistically call “liberal democracy.” In reality, real power, especially economic power, remains in the hands of the former colonial masters while their puppet native rulers are allowed to determine the domestic political agenda so long as it doesn’t hinder their continued acquisition of riches from the countries they control behind the scenes.

A good example of this arrangement, perhaps the first of a kind, was seen in what appeared to be the “independence” of the Philippines in 1946. The process leading to Filipino independence began in 1934 with the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Law. Under this law, the Philippines established a government known as the Philippine Commonwealth which was to steer the Philippines through a 10-year transition period. After completing 10 years of nearly autonomous governance, the United States was slated to withdraw its sovereignty over the islands on July 4 of the succeeding year and recognize the Philippines as an independent republic.

However, due to the three year-long Japanese occupation of the Philippines during WW II, the US postponed granting formal independence to the Philippines until July 4, 1946. But in exchange for its independence, the Philippines was required to accept the Bell Trade bill, originally authored by Representative Jasper Bell. The Bell Trade bill required the extension of free trade relations between the United States and the Philippines for eight years following independence, after which tariffs would be gradually imposed for 20 years.

More importantly, American individuals and corporations that invested in the Philippines were to enjoy the same rights as their Filipino counterparts, i.e. the right to own land, acquire natural resources, etc. This meant that small Filipino business owners had little hope of successfully competing with American capital. The Bell Trade Bill also tied the Philippine peso to the US dollar and could not be independently revalued. In short, the Filipino economy, especially the right to extract natural resources as well as profit from cheap Filipino labor, remained in American hands as before.

Another condition of Filipino independence was granting the US the right to continue to maintain military bases in the country in the name of protecting American interests in the region. The “American interests” the bases were protecting, however, were those of American businesses, ensuring that no one, including the Filipino government, would be able to interfere with the right of American business interests to enrich themselves at Filipino expense. Today, China is often criticized for having militarized islands in the South China Sea, but actually it was the US that first militarized the biggest island chain in that sea!

On the one hand, it is true that the Filipino people, by and large, welcomed their country’s independence in 1946, for it did mark the end of formal aspects of colonial rule. For example, there was no longer direct US oversight, no more American High Commissioners, the Philippine flag flew by itself (except on US military bases) and the Philippine National Anthem was played alone. But Filipino critics of this arrangement have long argued that the day of Filipino independence also marked the beginning of a neo-colonial relationship. Critics note that the US would never allow its own independence to be conditioned on granting similar privileges to citizens of a foreign country.

It can be argued that the 1946 creation of a neo-colonial relationship with a former colony was a farsighted move on the part of the US. Why? Because, by and large, the remaining Western imperialist powers in the post-WW II era initially sought to use force to regain or maintain their far-flung empires in Asia and Africa. However, faced with ever growing and often violent “national liberation movements” in their colonies, the Western powers eventually agreed to their formal independence though only on the condition they accept neo-colonial provisions similar to those imposed on the Philippines by the US.

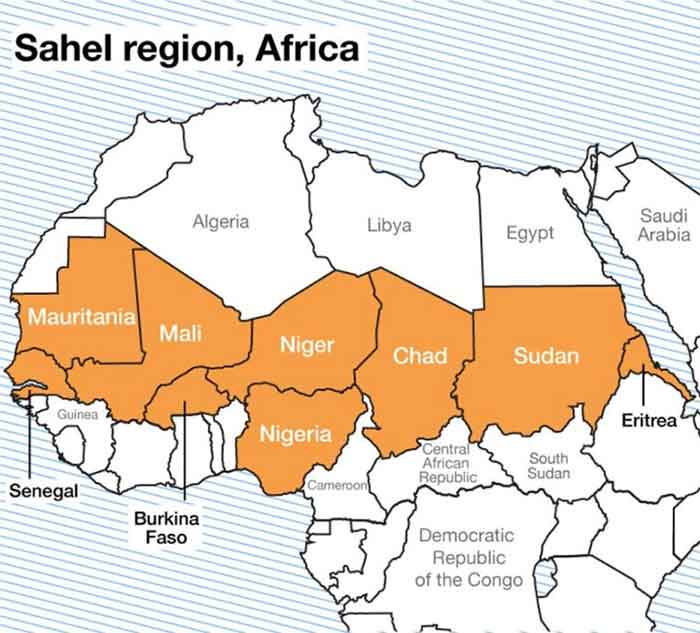

The French, for example, initially attempted after WW II to hold on to their former colonies by force as seen in their violent struggle to reclaim their colonies in Indochina, i.e. Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. However, following their stinging defeat at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the French finally realized that they, too, would have to adopt neo-colonial policies if they were to maintain control of their remaining colonies. Today, France’s ongoing neo-colonialism is most visible in its former colonies in Africa, colonies that today account for 17 modern nations, stretching from Morocco to the Congo.

Similar to the Philippines, each time a French colony in Africa became independent, it was forced to sign a “Cooperation Agreement” with France. Once again, the agreement allowed for the continued exploitation of the new nation’s natural resources by the corporations of its former colonial master. Once again, the French military was given the right to station troops in the new nation indefinitely. Once again, the currency of the new nation remained under French control.

In light of the continued economic exploitation of former colonies by neo-colonialists, it is not surprising that, from time to time, local political leaders emerge who attempt to free their countries from economic exploitation. When this occurs, neo-colonialists typically first try to bribe the native rulers into acquiescence. Should that fail, it becomes a question of using one or another method to oust them from their positions or, if necessary, assassinate them. If all else fails, the ultimate or final solution is direct military intervention. For example, in the case of France, since 1960 the French military has intervened more than 50 times to ensure the attempt to gain true independence ended in failure.

According to the late William Blum, a former US State Department employee turned journalist and historian, between the end of WW II in 1945 and 2014, the CIA has attempted to overthrow at least 57 governments, sometimes multiple times, and was successful on 36 occasions. Some of the best known of these is the 1953 ouster of the democratically-elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mossadegh, because he had nationalized the Iranian oil industry previously operated by British companies. Mossadegh was forced from office and arrested, spending the rest of his life under house arrest.

In the 1950s, the democratically-elected President of Guatemala, Jacobo Árbenz, attempted a series of land reforms that threatened the holdings of the US-owned United Fruit Company. The CIA arranged a coup in 1954 that forced Árbenz from power, allowing a succession of military juntas to take power. The CIA’s involvement included supplying arms to the rebels and associated paramilitary troops while, at the same time, the US Navy blockaded the Guatemalan coast.

In 1960, Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Congo (later the Democratic Republic of the Congo), was forced from office amid the US-supported Belgian military’s intervention in that country seeking to maintain Belgian business interests following the country’s decolonization. Even after leaving office Lumumba attempted to fight back and was targeted by the CIA as a threat to the newly installed government of Joseph Mobutu. After an aborted assassination attempt against Lumumba involving a poisoned handkerchief, the CIA alerted Congolese troops to Lumumba’s location and noted roads to be blocked and potential escape routes. Lumumba was captured in late 1960 and killed in January of the following year.

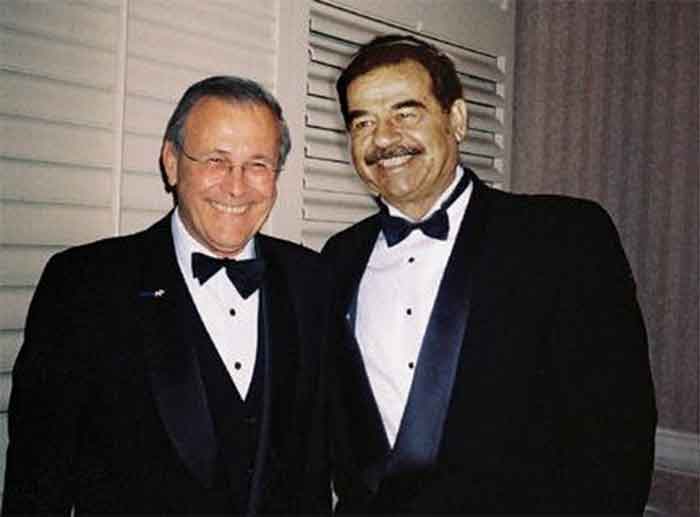

The preceding three examples are literally no more than the tip of the iceberg in revealing the CIA’s role in maintaining neo-colonial control of former colonies, not only its own but those of former European imperialist powers. The best known example of the US ‘last resort’, i.e. the outright use of the US military, is no doubt the US coalition-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003. What is little known, however, is that the CIA had, prior to the invasion, attempted to overthrow Saddam Hussein on its own.

It was with this end in mind that the CIA first recruited Ayad Allawi, head of a network of Iraqis opposed to Saddam Hussein, to be part of its operation. Using Allawi and his network, the CIA directed a campaign of anti-government sabotage and bombing in Baghdad between 1992 and 1995. Nevertheless, Allawi’s attempted coup against Saddam in 1996 was unsuccessful, something that eventually led to the 2003 US invasion. Following Saddam’s overthrow, Allawi served as the first interim Prime Minister of Iraq in October 2003, providing an Iraqi face for the ongoing US military occupation.

At present, many countries justifiably condemn Russia for its invasion of Ukraine. Given this, one might hope this would lead the US and other European powers to reflect on their own ongoing, neo-colonialist control, including military invasions, of their former colonies. However, at least as far as the mass media in neo-colonial countries is concerned, this appears to be a forlorn hope. Instead, the media use the revulsion felt against Russia’s conduct to portray their own countries, by aiding Ukraine to repel the Russian invasion, as paragons of moral righteousness, dedicated solely to the promotion of liberal democracy (in reality, capitalism) and freedom throughout the world.

Nevertheless, the world has changed, especially due to the rise of China. Even now, its Belt and Road Initiative demonstrates to countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America that there is an alternative to being controlled by neo-colonial powers. This is one of the unspoken reasons China must be “contained.” That is to say, contained before the possibility of genuine independence from neo-colonial control is allowed to spread to the exploited nations of the world. Will the possibility of genuine independence be realized? Needless to say, the CIA will, as it has done so often in the past, do its best to crush this possibility. Backed by the US military, the CIA will seek to maintain the status quo, ensuring the rich continue to get richer and the poor, poorer.

While I would like to end this article on an optimistic note, the way forward will be long and exceedingly difficult. I can only express the hope that each one of us will do whatever possible to bring an end to neo-colonialism just as its precedents, slavery and colonialism, were ended. But make no mistake, in light of the economic and military power of those who benefit from neo-colonialism, the struggle won’t be easy.

Brian Victoria, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies