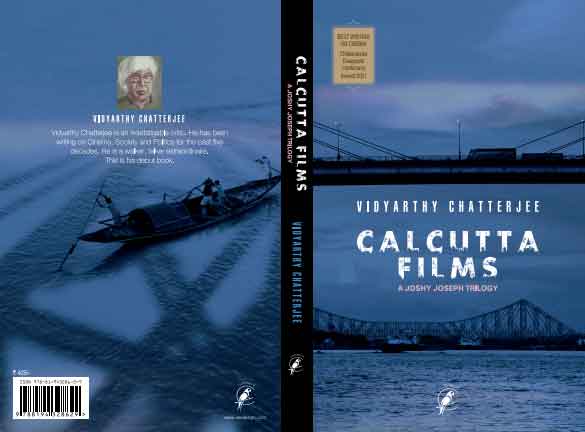

The Chidananda Dasgupta Best Book Award to Vidyarthy Chatterjee’s book on Calcutta and the Joshy Joseph Trilogy- A critical review

Published by Cerebrum Books, India, 2022

Stuart Hall identifies three ways of reading media messages.[1] According to Stuart Hall, Dominant Reading takes what the film says for granted. The Negotiated Reading questions the minor premises but accepts the major ones. The Oppositional Reading completely subverts the narrative. All these positions are available to any reader. Psychoanalysis adds a further caveat; we read something the way we do because we want to read it that way. This implies that the dominant reader cannot absolve himself/herself of his/her responsibility of having read the text in terms of his/her preferred or privileged meanings. It proves his/her complicity in saying ‘yes’ to the ideological configurations of the film, however, tacitly the whole operation may occur.[2]

But Vidyarthy Chatterjee’s prize-winning book – Calcutta Films -A Joshy Joseph Trilogy does not fall in any of the above descriptions about media-reading mentioned by Stuart Hall. Vidyarthy Chatterjee’s approach to reading three major films of Joshy Joseph comprised of One Day in a Hangman’s Life, A City A Poet and a Footballer and Obhimani Jol (Walking Over Water) goes far beyond the cinema of Joshy Joseph and ventures into the political turbulence West Bengal in general and Calcutta/Kolkata in particular has passed through over several decades. Unlike most auteur critiques of a single filmmaker which choose to stick to a critical or theoretical or structural analysis of his/her films, Chatterjee takes a much more holistic and wide approach. He liberates the reading of the three films of Joshy Joseph from any ideological or critical or analytical trap and throws them out in the midst of his personal views on the ever-changing – mostly for the worse – socio-political scenario of West Bengal in general and Calcutta in particular. Add to this, we get a glimpse into the author’s personal history of growing up in Jamshedpur, studying in a missionary school, working with his father and older brother on his father’s news magazine published for many years in English, his long but intermittent stays in parts of Kerala and so on.

The 222-page book is divided into five chapters after an interesting prologue that explains “Why I Wrote This Book.” The other chapters are (a) A Prologue by way of emphasizing the director’s Pan-Indian detours to arrive at the heart of the matter – Calcutta, (b) One Day from a Hangman’s Life, or film as a morality play, (c) A Poet, a City and a Footballer or Film as Philosophy, (d) Obhimani Jol – Walking Over Water, or film as an engagement with the primary element, and (e) an epilogue by way of establishing violence as a metaphor for Calcutta and an extended hinterland.

This last-mentioned chapter is further classified into (i) The LC (Local Committee of the CPI(M) Government in West Bengal) As An Instrument of Violence, (ii) Sacrifice as an idea, (iii) The mob pits itself against the Left Sentiment, (iv) Violence of Unjust Banishment, (v) Violence of looks to intimidate the Subaltern, (vi) Thread of Violence to hold the Trilogy Together, and (vii) Concluding the Conclusion.

These sub-chapters, all, except the last one which comes back to Joshy’s three films, define a detailed history of the changing iconography of politics in West Bengal in general and Kolkata in particular where he not only launches a fearless, no-holds-barred verbal attack on the ruling political parties focussing on the 34-year-rule of the CPI (M) in Kolkata without sparing one kind word even for its iconic leader Jyoti Basu. This goes to show how deep Vidyarthy has dug into the murky underbelly of politics in West Bengal and its capital which is also the “cultural” capital of the country.

Is the book a platform offered to the rather distanced writer to let off steam and anger at the political scenario the country and the state has come to? Red, or green or orange, his anger is distributed, albeit unequally, among the colours politics wears on their scary, loud and bizarre flags. Or, is it a genuine intention to study the films of a filmmaker who is also his close friend? Or, is it as a token of deep gratitude he feels for a man who, other than being his drinking companion, has given him a shoulder to weep on when sad, or, a close hug when happy? Chatterjee’s descriptions of his days spent in Kerala in Joshy’s ancestral home suggests this warmth between author and subject.

Chatterjee approaches his subject, Joshy, solidly by establishing his credentials with some of this veteran documentary filmmaker’s notable past work such as Making the Face, Wearing the Face, Status Quo and Mobile with his personal perspective on Joshy’s works before arriving at the three major films that he chose to analyse.

Incidentally, One Day From a Hangman’s Life was stopped from screening at Nandan II some years ago, though it drew more crowds than Shyam Benegal’s Bose– The Forgotten Hero. This stoppage created a long and close bonding with human rights activist, writer and crusader Mahasweta Devi. The film captures a day in the life of Nata Mullick, the hangman who pulled the noose around the neck of rape-and-murder convict Dhananjoy Chatterjee, shortly before the excecution. Joshy offers the film as a self-critique on how a filmmaker makes no bones about capturing a recalcitrant subject through every devious means he can imagine. Chatterjee, however, keeps his focus on the hangman and his desperation to gather how much money and media hype he can garner from a greedy media which he knows will disappear the minute the media is done with its quota of bytes. Chatterjee’s epilogue of the “film as a morality play”[3] points this out.

Chatterjee’s take on A Poet, A City and a Footballer is outstanding as he has focussed his microscopic eye on the finer nuances such as the comments given on camera by the deceased Poet Gautam’s former wife Laboni Sarkar, an actress’s take on her former partner in powerful terms and how, on hindsight, these have a strong feminist slant. Sarkar’s voice-over recites one of Gautam’s poems. The voice precedes the visuals that show Laboni talking about how a Bohemian like Gautam does not understand the pain that affects his close ones who are not Bohemian and cannot understand how the Bohemian mindset works. Or, the poet’s father’s expression of grief on his young son’s demise without allowing it to be soppy or sentimental at any point.

Walking Over Water marks a difference. It explores the internal fragmentation within Joshy’s personal family relations with his wife who thinks making films imposes a curse on the family while Joshy’s life is defined by his deep involvement with films and how this friction has a deep impact on their son Ozu. This is part-fiction and part-documentary but the director fuses both in a way it is difficult to distinguish the one from the other.

This is interesting when juxtaposed against Joshy’s 1999 film Sentence of Silence. This film won the National Award for the Best Film on Family Welfare. It is a strong film that redefines the family ethos of changing social circumstances of the Indian Christian community the Catholic Church does not grant divorce to. The film resulted in the bringing in of a new statute named Indian Marriage Act exclusively applicable to marriage between Christian men and women.

Walking Over Water is a must-mention because of Joshy’s abstract, Godardian homage to cinema in the name and style of Obhimani Jol. Water, as Chatterjee rightly points out, is all around us and this is what Joshy plays around with – water as a physical truth, water as a metaphor suggesting the conflicts in Joshy’s family life, the bonding sustained with its united faith in Christianity, and water as a visual, cinematic truth as it appears like a shelter Ozu often repairs to with his older friend which may or may not be a girlfriend.

The question now is/are – how much of the book is about Joshy Joseph’s Trilogy, how much it is about the now-rarely-discussed fiery and tragic political history of the State and its capital and how much the book is about the author who wrote it – his first book which won a prestigious and much-contested award. The answer is simple – it spans all three worlds of Joshy Joseph, the political history of Kolkata and the world of Vidyarthy Chatterjee himself which makes the book an example of any Godardian film that defies narration and even, for many of us, definition. Or, is it, in a manner of speaking, as formless, as fluid, as fluctuating and as temperamental and as volatile as water itself? The book raises no questions, only throws up assertive statements on what the author has learnt to believe in. Powerful.

Let this end with Mikhail Lermontov’s quote: “Many a calm river begins as a turbulent waterfall, yet none hurtles and foams all the way to the sea.”

(Shoma Chatterji is a national award-winning author)

[1] Stuart Hall addressed theoretically the issue of how people make sense of media texts. He parts from Althusser in emphasizing more scope for diversity of response to media texts. In a key paper, ‘Encoding/Decoding’, Stuart Hall (1980), argued that the dominant ideology is typically inscribed as the ‘preferred reading‘ in a media text, but that this is not automatically adopted by readers. The social situations of readers/viewers/listeners may lead them to adopt different stances. ‘Dominant‘ readings are produced by those whose social situation favours the preferred reading; ‘negotiated‘ readings are produced by those who inflect the preferred reading to take account of their social position; and ‘oppositional‘ readings are produced by those whose social position puts them into direct conflict with the preferred reading (see Fiske 1992 for a summary and Fiske’s own examples, and Stevenson 1995: pp 41-2). Hall insists that there remain limits to interpretation: meaning cannot be simply ‘private’ and ‘individual’ (Hall 1980: 135). Taken from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/marxism/marxism11.html

[2] Ibid.

[3] A Morality Play is a kind of allegorical drama having personified abstract qualities as the main characters and presenting a lesson about good conduct and character, popular in the 15th and early 16th centuries.