Dir. Arvind Gaur

Written by: Ashok Lal

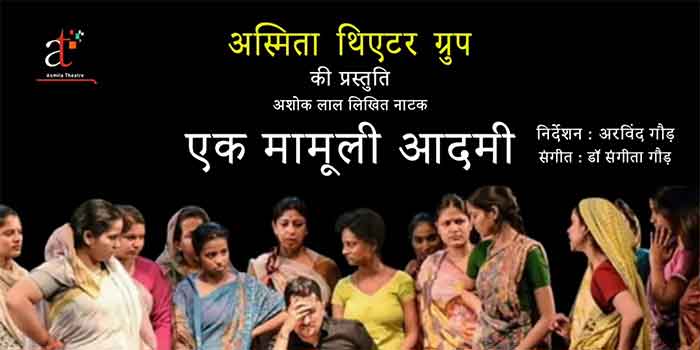

Presented by Asmita Theatre Group in Sri Ram Centre for Art and Culture on 29th July 2022

The black t-shirt wearing and exceedingly soft-spoken young volunteers we encountered outside the venue exuded such an intense awareness of the injustices of the world that I wanted to pat them on the shoulder and tell them, there there young man, the weight of the world does not rest on your shoulders, relax a little, take a break, maybe go open a bottle of old monk with your friends in some dingy room Delhi has allowed you a life in and smoke chota Goldflakes without, if you can manage it, discussing how to save society from itself. As it happened though, I just smiled at them and hoped they wouldn’t start a conversation about how there is no alternative to communism.

In the handbills they were religiously handing out, as if they were the prashad of this august gathering, I read that Mr Gaur, the director walking around in a hand cast, hopes that ‘this play makes relevant and positive contribution…and puts forth a fresh set of questions that we may ask of our society and ourselves.’ Now, as we know, Indian society does not ask itself too many questions, choosing rather to remain blind to its own rot. Therefore, it is always desirable for a work of art to raise questions which dispel at least some of the darkness. So, I thought, maybe, just maybe, the good people presenting the play will genuinely put out something worth watching, something that will, god forbid, even make us all think about how we have created such a depraved society and why we continue to live in it without doing anything about it.

But, that was not to be. The play rehashed the oldest stock characters known in caste-Hindu liberal art and that too with such a lack of self-consciousness that my friends thought they were watching some 1980s Bollywood movie. There were the Brahmin goons talking in shuddh Hindi, the corrupt and sycophantic officials either drooling or eating, the shayari spouting liberal of the famed Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb, the oily politician of the janta-janardhan guild, the loud basti-dwellers with their cute accents and broken Hindi, and even the Brahmin man who on being told he is dying of cancer decides to do something ‘good’ with the remainder of his life. The good Brahmin vs bad Brahmin trope was presented with such vigour and received such applause that it swiftly became clear that neither the presenters nor the audience had read Ambedkar nor anything written in the Ambedkarite tradition for the last 75 years. Can a Brahmin be good? Oh my heart, yes, all he has to do is not be corrupt. It is a wonder that these tropes can be used in 2022 without dying of shame.

Let’s take a look at the title for instance. Who is this ordinary man the title refers to? He is a top-tier Brahmin (Awasthi) working as a head-clerk in the municipal corporation of Delhi. In both class and caste terms, he easily belongs to the top 5 per cent in the country. By what standards exactly is this person ordinary and not elite? Who in this godforsaken country are the elite if these people aren’t? This obsession of the elite to present themselves as common men has reached such absurdities that Narotam Sekhsaria, the founder of Ambuja, writes in his autobiography that he is a common man; he, who grew up playing cricket with the Bajaj family in a house on Nariman Point! Anyway, back to the play at hand, at some point Awasthi says his problem is that he doesn’t know how to spend his money, which another character in the play even acknowledges is a very unique problem, certainly not the problem of an ordinary man, who is always short of money. Speaking of, this other character, Mr Khare, in charge of sanitation, is the lone voice of the liberal Brahmins in the play. And how is his liberalness established? He drinks, eats meat (or, as he calls it, non-veg)—possibly not beef (he is not a radical!) but definitely chicken—he is unmarried, a regular visitor of prostitutes, he does not respect Pandits and, last but not the least, he is an afficionado of shayari, from Ghalib to Gulzar. There is nothing in the character that is not a ghisa-pita stereotype—he even drinks Old Monk (which drew applause from the crowd because all left-liberals are apparently nostalgic about the days when they could drink Old Monk in caste sanitized college hostels).

Awasthi is a soulless man in a soulless job, shuffling files and counting down his days silently in a secluded corner of the world, enjoying his caste privileges with no understanding of them and not hurting anyone consciously (so very much like most of the audience). His awakening, so as to speak, happens not because he makes an encounter with the suffering of the Other like the Buddha but because he is told of his own impending demise through cancer. The tools of his awakening are not books, like they were for Ambedkar, but a night of alcohol filled revelry, replete with prostitutes and singing in the streets of Delhi, and a day of treating himself to shopping, good food, movies and even the amusement park with a ditsy girl who has cute nicknames for everybody at office and thinks life is just such a peach (she is happy about going to work in a toy factory!). One can almost see the montages that would be used were this a film. We have all seen those movies where a straight-laced hero achieves his potential after ‘opening up’.

And what does Mr Awasthi do after his awakening? Does he reject caste (and by extension Hinduism) and convert? Does he give all his money away to the basti-dwellers so they can build a school or a clinic, or improve their living conditions, or hire a lawyer to get a stay order on the inevitable demolition that is going to impinge on their lives? Does he do anything that hurts the caste order or improves the lives of the basti dwellers in any significant way? No, of course he does not. He has a son married to a Brahmin girl (both of whom are exceedingly ignorant), he has in all likelihood given money to Brahmins all his life, he doesn’t have a single Dalit friend or acquaintance but he has dealt a deathblow to caste by helping to build a park near a basti.

He is even presented as a hero who went against his own caste. So much so, that Pandits refuse to come to his tehravi (oh the horror!), which incidentally is the central plot of the play—Awasthi’s son on a journey to discover why pandits won’t come to his father’s tehravi even though his father was a top-class Brahmin. But did he really go against his caste? All he did was talk to people nicely, follow the letter of the law and not engage in overt corruption. The Gandhian overtones are clearly apparent. All that we require is a change of heart in the Brahmins and then everything will be great. And even this change of heart is going to be achieved on the backs of the lower caste. The basti people exist as if to allow the Brahmin to live, to be a better version of himself. He literally is a vampire who after living all his life on their labour now also takes his emotional sustenance from them because his own Brahmin society has become completely loveless and thus dead.

Incidentally, the play could have also questioned why Brahmin society has become like that while the people living in the basti continue to possess the powers of life. But it obviously does not do so. That would be actually raising some difficult questions for the audience. Instead, the play offers a solution to the audience for their own problems. You can’t engage with your own family and caste brethren anymore? Worry not, just go do some little thing for basti dwellers and everything will be alright, you will be content, your family will start to understand and love you, and everyone will live happily ever after, except of course the long forgotten basti dwellers who will continue to live in the basti while being plot elements in the universal drama that is YOUR life.

It is telling that of all the demands the basti dwellers made or could have made, it was the park which the play chose to concentrate on. Why do the upper caste have an obsession with giving parks to basti dwellers? Is it something to do with the desire to give them their own public space so they don’t intrude on the public spaces of the upper caste? Is it because the biggest problem that upper castes have with bastis is their aesthetics? Since the upper caste don’t live there, they neither have any understanding of nor any empathy for the lives being lived in bastis. But they can see and smell the bastis, and they don’t like the dirt they see or the stench they smell. Since they only experience the basti aesthetically, they are obsessed with improving the aesthetics of the basti. Forever building parks, engaging in art projects, cleanliness drives, etc. without ever getting into the actual problem of the basti.

They pretend that the addition of the park has made life better for the basti-dwellers without getting into the question of why the basti exists at all. There is no dearth of literature written by basti-dwellers which says that the addition of a park does not make any meaningful change at all to the lives of those who have to grow up in a basti. But, of course, who reads literature written by basti-dwellers, right? Well, even James Baldwin talks about how adding a park to the slums of Harlem does not make any difference to anybody in Harlem, all it does is gladden the hearts of the White administrators who imagine they have done something for the underprivileged. This play, in fact, is about how building the park gladdens the heart of a Brahmin administrator. The park is his good deed before he goes, so he can clean up his karma and presumably be born as a Brahmin again in the next life.

Instead of expressing a social dilemma or asking a question of society, the play seems designed to assuage the hearts of upper caste liberals so they can continue to persist in their ignorant slumber without taking recourse to therapists and antidepressants, which a lot of them do need these days just to get by on a daily basis. At least judging by the reaction of the left-liberal upper caste audience, they were very happy with such an approach. There was lots of laughing and clapping. Especially at the bits where casteism was being caricatured in order to be knocked down ever so easily with a word or a joke, the parts where the pride of the bad Brahmins was being upended, and the parts where that goof Awasthi was being just oh so innocent about the world. There was also some gasping and sensitive emoting when Awasthi was in the throes of his loneliness and despair, when he mentioned his broken familial relations, and when he was treated badly by his boss or by goons. There was especially much oohing and aahing at the gratitude which the basti-dwellers showed for the good Brahmin Awasthi, for that is how the audience would also like to be treated by those forever ungrateful under-privileged they go out of their way to help.

Finally, the difference between caste and casteism is not understood at all by the presenters of the play. The play argues against casteism while being the perfect example of how caste works. Yes, a person should not behave in a discriminatory manner. Great. But should a play being put up in 2022 not pay attention to casting? While the pandits are played by Brahmins, which is all well and good, the basti-dwellers are also played by upper castes. One of the basti-dwellers is even the director’s own daughter! What stopped the director from getting actual basti-dwellers to play the role of basti-dwellers? After all, basti dwellers in Delhi do engage in a lot of street theatre, so there could have been no dearth of actors to choose from. And yet, the director is unable to look further than his own daughter; if this kind of nepotism is not part of the problem of caste, then what is? A play that purports to be anti-caste could have at the very least been put up with a little more circumspection.

The play is based on a movie by Kurosawa which was made in 1952. I don’t know if that movie made any relevant and positive contributions or raised a fresh set of questions for Japanese society of that time, but I can say with confidence that this play is not only totally irrelevant today but makes a negative contribution to society by allowing caste-Hindus to think they will be let off the hook by such token gestures as building parks, and it is so stale that consuming it might give one spiritual poisoning. Plays like these need to be stopped for the general good.

Akshat Jain is a writer currently residing in India. He uses the debate methodology of Syādvāda to piss people off. Like a good Syādvādist, he claims that all his claims fall within the ambit of falsifiability.