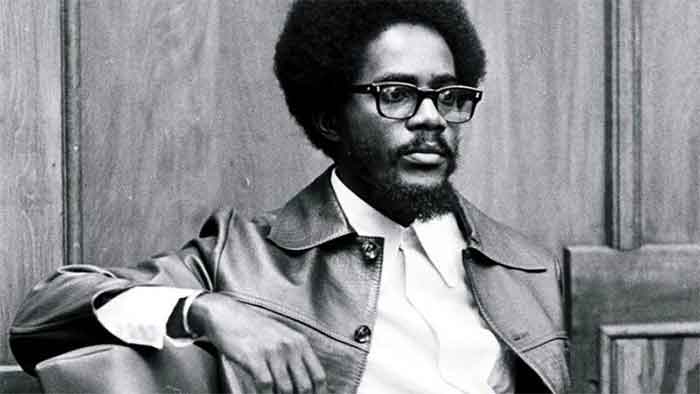

All of us who yearn to see a mass movement of workers united across national, racial and gender lines against capitalism and imperialism should remember and learn from the life of Walter Rodney. A Guyanese historian and activist who was murdered by his own ruling class in 1980 at the age of 38, Rodney understood the pitfalls of pseudo-socialism and neocolonialism like few others. And also like few others, he combined a profound understanding of history from a Marxist perspective, the ability to convey his knowledge and learn from broad swath of workers, and a commitment to actively participate in workers’ struggles. It is that combination that made him so dangerous to the Guyanese rulers.

It is difficult, in a brief article, to include any but the barest outline, of Rodney’s life, but his profound insights, his scholarly achievements, and his egalitarian relations and on the ground unity with workers are worth remembering and emulating. Much more about his life and ideas can be learned in the recently published biography by Leo Zellig, A Revolutionary for Our Time(Z), and Rodney’s masterwork, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. One can also visit The Walter Rodney Foundation, https://www.walterrodneyfoundation.org/.

Rodney was born in 1942 in then British Guiana to parents involved in the Peoples Progressive Party, the only multiracial mass socialist party in the Caribbean. After college he won a scholarship to study at the School of Oriental and African History at the University of London. There he joined a study group led by C.L.R. James, the prominent Trinidadian Marxist, author of Black Jacobins. In 1966, after a brief stay in Jamaica, Rodney left for a university appointment in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. After eight years he returned to Guyana where he was denied an academic appointment, but became a leader of the activist workers party, the Working Peoples Allliance (WPA) and an international speaker, teacher and writer.

There are three main aspects of Rodney’s work that make it important for us to know him today.

- He changed the racist construct of African history (a history white authors often said failed to exist) as written by capitalists to document the complex and varied history of the continent before Western invasion caused development to stall and retard progress through the present.

- He recognized that post-colonial “independent” governments, even those calling themselves socialist, remained the tools of the international capitalist system.

- He understood the necessity for working class based multiracial and anti-capitalist organizing, led by a party, in order to defeat both local and international capitalists and build a truly socialist society

A New History of Africa

Rodney’s masterwork, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (HEUA), was published when he was only 28 years old. Although the result of rigorous and wide-ranging research, it is presented without footnotes and references and in straightforward language in order to be accessible to the broadest range of readers. He begins with a chapter on the nature of development, the universal necessity for humans to come together in groups and create the “increasing capacity to regulate both internal and external relationships(p3).” Economic development depends on the understanding of nature, technology to manage nature and the way that work is organized. Everywhere, humans progressed along this path as they also developed ideologies and social beliefs. Generally, a period of communalism was followed by one of slavery when small groups became domineering, followed by feudalism where land and wealth were in the hands of a few in an agricultural society. Next came capitalism, in which machines were the main engines of production, but remained in the hands of a tiny group, the bourgeoisie. This small class of industrialists, financiers and craftsmen then bought the labor of others, the working class. In some areas and eras the transition between periods was gradual and in others violent and revolutionary.

Development varied and the pace was uneven throughout the world, but a major point of the usual European view that Africa was backward, savage, before the West came in contact, is wrong. Rodney devotes much time to describing the history of Africa before 1500. Some examples of African development include Egypt from 2000 BC, and the later empires of Ethiopia, Ghana and Western Sudan. In other areas, there were communities of hunter gatherers and farmers with an advanced understanding of the local ecology, including plant and animal life, soil, climate, and their interrelationship – all well-established before the 15th century. Skills such as home construction, medicine, mining, handicrafts bronze and iron working were also developed by special practitioners. When the Europeans first arrived they were astonished to find gold being mined and traded or the magnificent ruins of buildings in Zimbabwe, which Cecil Rhodes assumed had been built by white people.

From 1500 t0 1885, African society was greatly and catastrophically influenced by Europeans who traded in slaves, ivory and gold. At first only the coastal regions were affected, but gradually the whole continent was caught up in this commercial domination of Africa by Europe. Along the way there were many attempts at resistance, including that by Angola in 1648, King Agaja Tudo of Dahomey in 1724, and the attempt by Tomba to unite the people in small states in what is modern-day Guinea in the 1720s. These efforts were defeated by superior European arms, and overall the wholesale export of capital to Europe from Africa proceeded. Capitalist growth was not only from stolen labor but the development of shipping, insurance, technology and the manufacture of machinery.

Europeans refused to trade any technology to Africans, especially that to make gunpowder and firearms. African efforts to develop industry, such as the Egyptians attempt to produce cotton, or other efforts to manufacture glass and paper in North Africa were rapidly quashed. The wholesale removal of young men and women, who made up most of the 12 million enslaved by Europeans, resulted in almost total stagnation of the African population from 1650-1850, while that of Europe rose by about 275% and Asia by 255%. It also became necessary for Europeans to justify the enslavement of Africans by the promotion of racist ideas casting blacks as inferior and fit only for physical labor directed by others. These are the factors that led to the “underdevelopment” of Africa, which had its greatest divergence from European development during these centuries.

From Slavery to Colonization

During the years of slavery there also grew a group of Africans who collaborated with European exploiters for their own advantage, including many children of European fathers. These henchmen helped to establish the next stage of colonial rule and exploitation after so-called independence. Although “local” companies, banks, and mines may have appeared to run social operations, the profits all landed in Europe (including the US after WWII). What educational institutions were set up were designed to teach the superiority of Western ideas and culture and provide just enough educated natives to fill bureaucratic positions. European powers dictated what crops they wished to buy for export, such as cocoa or nuts, and regions that had been self-sustaining with varied agricultural products were reduced to total dependency and subject to famine. Rodney thus shows the development of local bourgeois classes with a foot firmly in the capitalist door as he also describes the lowly state of the majority of workers within the imperialist nations.

Although HEUA was written during the rise of the black power movement around the world, Rodney saw the necessity of raising the consciousness, cohesion and capacity for action of all black people – by whom he meant all non-whites – in order to oppose racism, capitalism and imperialism. However, the whites to be opposed were the ruling elite. He was in support of a multiracial society of the future “where each individual counts equally,” but not to promoting a myth of a multiracial society “designed to justify exploitation.” (The Groundings with My Brothers, p 29)

Meeting “Socialism” in Tanzania

Tanzania became independent in 1962, and its first president was Julius Nyere, who considered himself a socialist. However, his main objective in office was national sovereignty and independence from Britain. The UK was still needed to purchase exports and to run companies needed for trade; white officers still led the army. Nyere’s so-called socialism looked to his country’s egalitarian communal past as a model without confronting the class-divided present. He considered capitalism a reflection of individual moral weakness or greed rather than a system of productive processes. In fact, he pushed peasants to work harder to make up for underdevelopment. University students considered themselves part of the elite, the same elite that had been empowered by the British and still ran much of society. Rodney and other progressive faculty began a series of lectures on African development and a class analysis of society.

In 1974 the sixth Pan-African Congress, the first to be held in Africa, was to be hosted by Tanzania. Many formerly colonized states, including those in the Caribbean and most of Africa, had attained independence over the preceding two decades. The call for the conference stated: “the congress must draw a line of steel against those, Africans included, who hide behind the slog and paraphernalia of national independence while allowing finance capital to dominate and direct their economic and social life.” C.L.R. James was one of the main authors, and he presented it to Rodney. James’ and Rodney’s vision was, along with many others, that opposition groups and radical movements, such as the South African liberation struggle, should attend the conference. Prior to the meeting, Rodney wrote a widely distributed paper urging a Marxist analysis that emphasized class struggle versus imperialist led neo-colonialism. In the end, Nyere of Tanzania, Mobutu of Congo, Banda of Malawi, Sekou Toure of Guinea and other leaders tied to their former colonial rulers had the conference to themselves and anti-colonialist movements were barred. Rodney and James did not go (Z p184-8), and Rodney must be valued as an early alarmist against the dangers of falsely labeled socialism and the failure to rely on class struggle and working class power.

Return to Guyana

As he had always planned to do, Rodney returned to his roots in Guyana in 1974, not only to allow his children to experience their heritage, but to be better able to organize revolutionary struggle as a native son. Now a renowned scholar and lecturer being offered posts around the world, he hoped to attain a position at the University of Guyana. However, since 1964, the country was under the leadership of Forest Burnham, supported by the British and Americans, who had engineered the overthrow of the progressive leader Cheddi Jagan. Burnham’s relationship with the imperialists was felt to be reliable enough for them to allow British Guiana to become independent Guyana in 1966,(Z p217-222) As opposition to his rule grew, Burnham declared that Guyana was socialist and nonaligned, although he continued to run the same corrupt government and promote racial division. Burnham also made sure Rodney could not teach at the university.

Although he had to travel around the world teaching and speaking to support his family, Rodney also became an avid working-class organizer in Guyana. He was a major leader of the WPA, established in 1974 as an avowedly revolutionary organization with socialism, not pseudo-socialism, as its aim. It was involved in large wildcat strikes of bauxite workers, sugar workers, and struggles against police brutality, among others. As always, Rodney spent much time talking with and listening to rank and file workers.

Guyana had two main ethnic groups composing its working class: Afro-Guyanese, the black descendants of slaves, and Indians who came fleeing poverty and famine in India to a life as indentured laborers. Rodney recognized the vital importance of uniting these two groups in struggles for reform and revolution. “No ordinary [worker] can afford to be misled by the myth of race, “ he said,(Z p226) In 1974 he published A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905, in which he showed the unity of interests between the two groups.

So dangerous was the radical multiracial struggle led by the WPA that Rodney and other leaders were marked for arrest and assassination. In 1980, at the age of 38, a government under-cover agent sold Rodney a walkie-talkie that exploded in his hand and killed him.

A Legacy to Remember and Emulate

Had Walter Rodney lived longer, he would have witnessed the corroboration of many of his insights. Even movements in which he had hope, like the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa and the anti-imperialist movement in Angola, did not led to the freedom or advancement of the working class as socialist ideals were abandoned. Rank and file workers were not empowered, capitalist economies remained, and ties to Western financial interests and former colonial rulers were not broken. The same can be said of the many national liberation struggles of the Americas, from El Salvador to Nicaragua (and many others) that talked of socialism and practice capitalism. Most of these failures can be attributed to the errors of the Soviet and Chinese revolutions, who despite their early progress, came to value alliances with “good” capitalists and industrialization over building a truly egalitarian worker-led society. Many even well-intentioned socialists followed their lead. The other great pitfall of the liberation age has been identity politics, the valuing or racial or national identity over class. Thus even rebelling workers have been misled over and over by leaders who gain their loyalty them by virtue of their supposed unity with workers of the same nationality or race.

Rodney foresaw these developments in his critique of the movements he witnessed. He also had undying faith in the ability of workers to understand history and political analysis and unite and act in their own interests. Unlike many leftist academics, he knew that he could learn as much from workers as could they from him and that he too was obligated to partake in the class struggle. That is why we should read both his writings and the story of his life. That is why we must build movements that rely on the multiracial working class instead of capitalists and politicians and strive to ultimately do away with capitalism and imperialism, even as we fight reform battles.

Ellen Isaacs is a physician and long time anti-racist and anti-capitalist activist. She is co-editor of multiracialunity.org and can be reached at [email protected]. This article first appeared on multiracialunity.org