by Balmurli Natrajan and Raghav Kaushik

Dr. Balmurli Natrajan is Professor of Anthropology at William Paterson University of New Jersey, USA. He works at the intersections of the material and the symbolic, of the biocultural and political economy, and of culture, cognition and practice. His key research and teaching foci fall into three domains: group formation & inequalities (caste, race); culture, identity, practices (community, variation, transmission); and development (sanitation, domestic work, indebtedness, livelihoods). His book Culturalization of Caste: Identity and Inequality in a Multicultural Age (London: Routledge, 2012) is an ethnographic study that maps out the current form of legitimization of caste in India and problematizes caste identity.

Over recent years, the phenomena of caste and casteism have gained media attention in those spaces where the Indian diaspora is significantly present (e.g., USA, UK, Canada, and Australia). This is partly because of the increasing visibility and audibility of an anti-caste Dalit movements in India and in the diaspora, the most recent in the citadels of high-technology assumed to be caste- (and race, gender) free, but also a renewed interest in the comparative possibilities of caste and race especially in the wake of the George Floyd murder and the subsequent Black Lives Matter movement. This interview with Prof. Natrajan is set in the context of a need to deepen, clarify, and sharpen the understanding of caste and casteism in an accessible manner that brings deep scholarship to bear on caste as a matter of urgency. Too often, we feel that activism and scholarship are sought to be kept apart by a form of anti-intellectual activism and academic elitism. Given the persistence of caste-based discrimination and socioeconomic gaps in India, and the increasing awareness of and testimonies about, and the continuing structural (and physical) violence faced by Dalits anywhere, there is an even more urgent need to think carefully about the persistence of caste as a form of violence and inequality. How does caste manage to exist despite the increasing awareness of it as an unjust system and practice? What does scholarship have to offer to activists who are concerned with combating its virulent character while simultaneously having to attend to the ‘cunning of caste’ (i.e., its ability to adapt to new contexts and generate new forms of legitimacy)?

The interview has two goals. The first is to bring back a sense of caste as a historical material rather than a timeless transhistorical entity, to convey a sense of caste not as a static but as a dynamic system, in flux, being challenged and changing with circumstances, often material circumstances. Given the complex and long history of caste, the interview will briefly outline the course of the caste system from a system of varnas to a system of jatis. Unlike the varna system which bore some similarity to other oppressive systems around the world, the jati system with its 4000 plus caste groups is peculiar to India. Our intention here is to provide a way for anticaste activists to sharpen our tools to dissect and challenge a nimble and protean form of injustice.

The second goal of this interview is to discuss the present form of caste that Prof. Natrajan refers to as “samaj” in his book-length study of the topic. Post-independent India’s Constitution identifies caste discrimination as a problem and in some ways, also identifies caste itself as a problem (we discuss in this interview the astute ways in which Ambedkar did so). However, especially in a modern era with the rhetoric of Diversity & Inclusion, caste is demonstrating its resilience by presenting itself as ‘culture’ or as ‘cultural identity’. Caste groups are represented as culturally “different” groups, and the fact that India has 4000 plus jatis is presented as a positive indication of its rich ‘diversity’. Former environment minister Jairam Ramesh, a well-known liberal, spoke about India’s diversity thus: “Indeed, India has the greatest diversities – seven major religions and numerous other sects and faiths, 22 official languages and over 200 recorded mother tongues, around 4635 largely endogamous communities.” The number 4635 refers to jatis, i.e., caste groups. Caste is also represented positively by the ethno-nationalist right in India. For instance, political commentator S. Gurumurthy describes caste as a form of social capital that reduces transaction costs in a capitalist economy. A section of academic work on caste too represents caste as defanged ethnicity. For instance, anthropologist Chris Fuller describes the changes in caste as a process wherein a “vertically integrated hierarchy decays into a horizontally disconnected ethnic array.” A positive view of caste groups as being horizontally disconnected and enriching diversity is only possible if we view caste groups as benign ethnic groups or cultural communities. Even in the Indian diaspora, where there is now a growing recognition of the impact of caste (especially due to the recent legal case at Cisco), there is a proliferation of caste-based associations (example1, example2, example3) that use the language of diversity and inclusion to justify their existence in the name of preserving their culture and identity.

It is understandable to look at all of this and believe that perhaps in today’s world caste exists somehow in a defanged form, without casteism, and even if caste based discrimination or bigotry does happen, it is at the margins of society. Prof. Natrajan calls the above phenomenon as the ideological process of culturalization of caste and the renaming of ‘caste’ as the more acceptable term “samaj”. His thesis, convincingly argued with a detailed ethnographic study, is that caste is merely demonstrating its resilience by legitimizing itself under new conditions as “samaj”; if we examine how “samaj” operates, we see how the core tenets of caste, namely social hierarchy, inequality, power or domination, patriarchy and class disorganization are in fact reproduced. In other words, caste even in this culturalized form remains a structure of violence. Activists that desire to annihilate caste should recognize this and resist attempts to present culturalization of caste in a positive light.

Q: Let’s begin by discussing caste as a dynamic system that changes over time and adapts to circumstances.

BN: Caste as an entity – whether viewed as social relations, social practices, social organization, social structure, or social category of classification – is a form of power and a form of inequality. The inequality is qualitative as well as quantitative, that is, caste inequality is in degree and modality. All of that is dynamic and changing. But it does not necessarily mean a linear change. It does not necessarily mean a teleological one either, that is, that caste is heading towards a particular end. Caste is always a reality that is acted upon by human beings. Humans produce it, work hard to keep it going, and work hard to change it. My understanding of caste therefore is to narrate it to ourselves as a part of history making. Why is that important?

Often trans-historical narratives grip us in an attempt to do the right thing – that is, oppose caste. Yet, when you go trans-historical, you don’t just do injustice to time, you also do injustice to space. For, caste changes over time and varies across space. Is there a caste system in India? It’s a very tricky question for scholars; maybe it’s a simple question for activists, and I am not putting activists down. I think of myself as an activist and publicly engaged scholar. But the fact is that there is immense variation across regions in India. Caste has become ‘modern’ in many ways. It is very difficult for people to openly acknowledge that they are casteist, that caste is good, and so on. This shamefacedness of caste is also its modernity. Instead, people will continue practicing casteism, but legitimize it in different ways. So we need to pay attention to the legitimation of caste – which changes over time. Caste morphs, not because it wants to morph, but because caste adapts to changing conditions. Conditions change and caste seems to be adapting very well to that. Thus, caste is a dynamic reality that legitimizes each of its forms over time and space.

Q: Let’s discuss how it has changed over time, beginning with an outline, before we go deeper.

BN: The dominant way in which caste has operated has changed over time. What we call ‘caste’ (from the Portuguese casta or kind, species, ‘race’), has firstly referenced the native concept of ‘varna’, and the argument that I prefer and I think there is solid evidence behind it, is that varna has in some way been a dominant way in which caste operates for some time. Then the term caste gives way to another dominant referent, varna doesn’t go away, but it gives way to jati. Finally, and in much more recent times, and this is specifically my book’s argument, caste has morphed into samaj. Varna, jati, and samaj are dominant forms of caste in particular periods of the history of India. This doesn’t mean that any of these forms withers away. In fact we know even in lexical terms that they haven’t gone away. Each remains, but with one form dominating others.

Q: How did the varna system develop?

BN: Firstly, one has to see that caste is a historical material phenomenon. In this part of the world, as in every part of the world, by the time we are in the period we’re talking about the formation of varna (from the mid-2nd to the mid-1st millennium BCE, that is about 1000 years), you have the production of food. Broadly speaking, the South Asian belt is made up of 3 agro-eco-zones. You have the hills in the northwest, and if you go eastwards, you have the jungles, and you have riverine valleys. Riverine valleys are where caste evolved. In some ways, you can argue that caste is neither a hill nor a jungle phenomenon. If it’s there it’s diffused. Why does it make sense in the riverine valley? Riverine valleys are where you start having surplus production of some kind, as the dominant sector of the economy turns from pastoralism and horticulture or even shifting agriculture to settled agriculture. You have the discovery of iron (which is around 1200 BC in South Asia), which is crucial to clearing forests and tilling the soil. This sort of production requires collective action. You start having division of labor, you start having specializations. You have local trade, not just remote trade which has been going on for sometime earlier.

As you start getting into these kinds of issues, that’s when you also start getting the formation of early states in this part of the world. Again, in terms of time, this is closer to the mid-1st century BCE and it varies across space (earlier states in the east and later in the west of the Gangetic plains). You have forests getting cleared, you have migrations of distinct social groups, with the discovery of iron you have agriculture coming as a major form of production of food, and that leads to auxiliary industries of artisans, you need a blacksmith, you need a carpenter and hence trade specializations. You thus need those who are not directly involved in production. You have people who keep accounts. You then have the formation of a state and its standing armies that comes out of what Romila Thapar calls a lineage society. You have smaller groups of people becoming larger groups of people by claiming kinship. A lineage is when you can identify a descent group, say up to 3 or sometimes even 5 generations. Many lineages form a clan (what is called a gotra) by claiming a common remote ancestor, who we don’t know. Anthropologists depict this claim as dotted lines (clans with claimed ancestry) in contrast to solid lines (lineages with traceable ancestry). So, we’re in the realm of imagination and fiction. There are lots of clans, and you read about them in the ancient texts, like the Mahabharata and Ramayana, and various other texts, including the Jain texts. Now, varna (or the form of caste in this period) is many such clans who claim to be of a kind or kindred. It is a very large, claimed descent group. Castes have clan exogamy and caste endogamy. (Sidebar: this is where race and caste clearly diverge. Kinship and family structures do not play a big role in racial formations.)

Varna emerges within this cauldron of state formation and changing mode of production with attendant group struggles. People in power or the ruling clans – the kshatriyas – usurp the monopoly of the state chiefly through ritually legitimizing themselves through large-scale sacrifices or yagnas – ways to claim high status as the allocator and distributor of wealth and the protector of people. The legitimizers of kshatriyas were the brahmins. This combo of kshatriyas and brahmins start imposing law and order on the commoners – known at that time as a vis (later divided into the vaishyas and the shudras) in some way. This four-fold varna system also starts having some notion of property because of all the surplus, leading to questions of inheritance, that is, who is family, etc. The need to figure out lineage for inheritance comes about clearly in this period. Here, you also get the formation of patriarchy. Varna, we have some evidence to show, is not necessarily by birth – although some groups such as brahmins are far more closed than others. It is more based on the social function certain groups have in society. You have a handleable number of varnas. At some point, there were 3, then it became 4, and stayed around that number (You don’t have completely crazy figures like 4000 plus which is the number of jatis at a later time) This makes India not peculiar but following a pattern in ancient societies. The varnas are somewhat similar to the estates in the Roman empire; you have the landed gentry, you have clergy, you have commoners or working-classes including merchant classes and things like that. Estates do have a notion of nobility which is what distinguishes it from class. Nobility has something to do with descent and birth, but it is not fixed. A lot of it can be in motion and a lot of that has to do with the fact that people could migrate and form alliances, not just as individuals but as groups; go and set up something somewhere else and try to claim a totally different identity and hence status.

Q: From the varna system, caste over the years transitions into the jati system. With a huge number of jatis, with hierarchies that are localized and complex, jatis are peculiar to India. How did this complex system evolve?

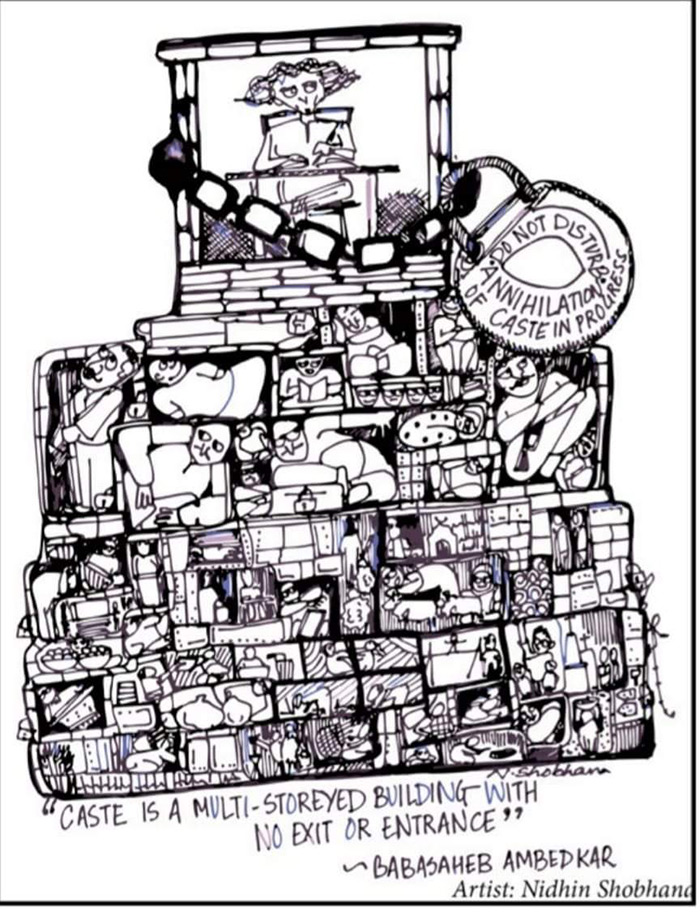

BN: The important thing about the varna system is that it was functional for the social order that was kept in place through the exercise of material and ideological power. That is, varna was based on the function you were carrying out in a hierarchical society, a function that was assigned to groups in historically specific ways. Jatis, on the other hand, are these thousands of largely endogamous groups jockeying for space in localized rank systems which are never clear; the only thing that is clear is the lowest rank. That’s the importance of the Untouchable vs all others divide, which I argue is the primary contradiction in a caste regime.

How did this evolve? It happened over a large period of time. One of the main analyses of this evolution is Ambedkar’s. He says that it is because brahmins first enclosed themselves i.e., became endogamous, and then this practice gets imitated unevenly and slowly but steadily across all varnas. He therefore calls “caste (or jati) as an enclosed class”, which was the basis of his famous statement that caste is not division of labor but a division of laborers. Social imitation is not an unreasonable idea. A lot of society operates through looking at what other people do, feeling social pressures. Imitation is a quintessential human way of learning. That’s what allowed us to live in every ecological niche, unlike any other species. Imitation of endogamy was over a very long period of time after the varna period. This same period also saw a gradual but steady increase in the ideology of pollution (and purity) within the complex of occupational especially craft specialization and indigenous gatherer-hunter groups who were dominated by ruling elites. The ksatriya-brahmin were increasingly joined by the vaisyas – to become the dvija or ‘twice-born’ on the basis of sacraments (i.e., rituals to designate them as superior), as opposed to the sudra who was known as ‘eka-jati’ or once born. This ultimately leads to the emergence of the practice of Untouchability (around 2nd-3rd century CE) with entire groups of jatis deemed to be permanently polluted, permanently outside of society except for the need for their labor, and condemned to marginal spaces, stigmatized and menialized occupations.

Functional classification of society (varna) was never enough in reality. New rulers emerge by usurping power through wars, new traders and merchants emerge, and there is always a need for people to till the soil and deliver particular services such as artisanal goods. For instance, there is a constant clash between who is a true Kshatriya and who is not. The late modern chieftain, Shivaji’s example is illustrative. Shivaji is a non-Kshatriya. In keeping with the earlier tradition mentioned above, Shivaji had to turn to the local brahmins to give him a genealogy and legitimize him as a ruler.

Jatis come about because social groups in power (based on kinship claims) seek to monopolize power, wealth and status. Just saying these are classes of people doesn’t allow for the work to be done. Indeed, classes in this part of the world segment into castes; the two are inextricably linked. All kinds of people end up doing almost all kinds of work and hence occupying different positions within the labor process. It needs to be understood that with the exception of priests, ritual specialists, and Vedic scholars (brahmins) on the one end, and menialized jatis (Untouchables) on the other end, all jatis potentially perform all kinds of functions in this period. If you take the example of peasants, you cannot say that only one varna is peasants. The vis was an enormous population – the bulk of society. It was dominated by certain jatis but it was never enough. Whoever was available to work worked. They may have gotten more pay if they were in a higher ranked jati. So, you have to see caste as a fluid thing. Functional groups and endogamous groups, varna-jati. This endogamy thing just grew on.

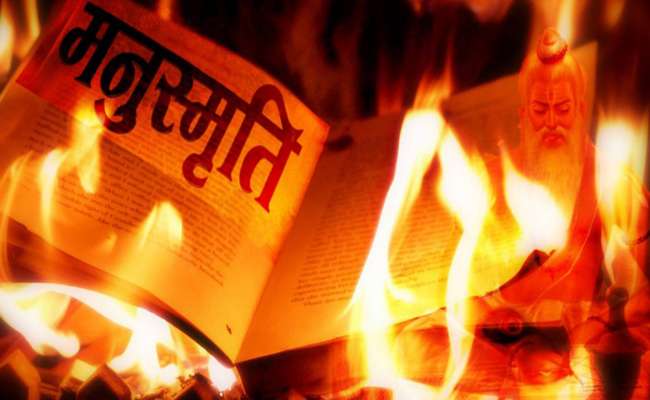

Throughout history, caste has been a form of power and hence, a form of inequality. There’s unequal access to resources, unequal ability to make decisions about social reproduction of one’s livelihood and social life (including status). Caste has also always produced its own justification. During the Varna period, Brahminism was its justification. Manusmriti was the text for that. As we start moving towards modern times, new ways of justifying were necessary because of changes in modes of production and the material reality. Around the colonial period, caste kept up by adopting another form of legitimation – Sanskritization. Whereas Brahminism says: “you are not like us, you are lower than us, and you can never be like us. Maybe in the next life, you can be like us.”, Sanskritization says something different. It says, “you are not like us, you are lower than us. But, if you do A, B and C like us, there may be a chance for you to be treated better, more like us.” Of course, Sanskritization was mostly an illusion – with few groups attempting it and with only some success. You need land to migrate, and you need anonymity in order to increase your status. And you needed to be able to ‘marry up’ or practice hypergamy. That’s how Rajput clans were formed. That’s how lots of groups started claiming Kshatriya status. Another example is the Lingayats claiming “higher” caste status. So, Sanskritization is this thing inter-twined with jatis.

Q: Now let us come to the topic of your book which is how caste has adapted post-independence.

BN: Post-independence, you have a robust Indian Constitution that identifies untouchability as a problem, and definitely identifies caste discrimination as a problem. But in its own subtle ways, the Constitution also arguably identifies caste itself as a problem. We see this when it makes a distinction between four kinds of social groups in India, three of one kind and one of another. The first three are: religious groups, linguistic groups and indigenous (adivasi) groups. It says all three have a right to their culture. Their life-ways are distinct, their languages are broadly different – linguistic and adivasi groups clearly have differences in language, and religious groups surely have distinct beliefs to some degree. As per the Constitution these three kinds of social groups have a right to culture.

The fourth kind of group is a caste group. There is nothing spoken in the Constitution about the right to culture of caste groups. The main protection that is needed for caste groups is the protection against discrimination. This is of course explicitly the case for Dalits or who are legally called as Scheduled Castes in the Constitution. The other three kinds of groups also need to be protected, but they have a right to propagate their culture. Note that Ambedkar did not include caste in the right to culture here. He was prescient in this respect. Why? Because then we would have had a Constitutional legitimization of caste as culture, and we would be in the realm of culturalization. What does culturalization do?

Unlike Sanskritization that says you do A, B and C you could become like us, Culturalization is like Brahminism – sufficiently adapted to the world of multiculturalism. Like brahminism it says: “you are not like us and you can never be like us.” But, unlike Brahminism, it doesn’t say that you are lower than us. Instead, culturalization says, “you are just different. And we will maintain the difference because mixing is a terrible thing.” This is what the scholar Pierre Taguieff has called mixophobia. Mixophobia exists right throughout history, even in Bhagavad Gita, where Krishna invokes the specter of Sankarshya, which means mixing or inter-mingling of castes, to describe what will happen to the world when social order collapses due to individuals not doing their caste-obligated duties. While the Indian Constitution does not support mixophobia, caste elites practice it. Indeed, the Indian state used to offer incentives for inter-caste marriage. Sometimes, mixophobia also gets reproduced among the non-elite or subaltern and oppressed castes. Even subaltern groups engage in protecting caste culture, as demonstrated by several ethnographic studies including my book on the intermediate caste of Kumhars, i.e., potters in Chhattisgarh.

We should always have our antennae up when caste is claimed as culture. There are all kinds of ways in which this works. For instance, take Khap panchayats or the village-based caste councils that take on the authority to adjudicate local caste disputes including to proscribe any inter-caste alliances or marriages. Khap panchayats say that these people (who have dared to love across caste boundaries) have to be killed or ostracized because this is our way of life, our caste culture. Political parties bow to them. I have written about this problem elsewhere. Culturalization is the default legitimation of caste today, more than Brahminism or Sanskritization.

Another example of culturalization is the recent statements of speaker of the Lok Sabha. After attending the Akhil Brahmin Mahasabha, the speaker said something like “Brahmins have always been the leaders of society because of their tyaag and tapasya” (sacrifice and penance). Note how culturalization camouflages brahminism. Instead of simply stating that he thinks that brahmins are superior (Brahminism), he goes to some lengths to justify the same by saying that brahmins are leaders because of their penance and sacrificing qualities or behavior, i.e., brahmins are known by what they do. However, who gets membership into the Akhil Brahmin Mahasabha? Do they test their members for the qualities of tyaag and tapasya? Of course not. Instead, we know that it is only those who are born brahmins who get to be its members. So, culturalization gives you this paradoxical view: To be a brahmin you have to do these things, but to do these things, you have to be born a brahmin. Birth-based logic parades as cultural traits (or learned and acquired behavior).

A third example, and one that gives the game away easily, is the Chennai-based interior work company which posted an ad in 2019 for the post of ‘General Manager’ that specified in brackets ‘Brahmins Only’. When this sparked outrage online, the company apologized stating that they meant to say ‘pure vegetarian’ instead of ‘Brahmins Only’. Here, an assumed cultural trait (vegetarianism, or to be really sure, pure vegetarian) is camouflaging the search for a birth-based identity of a candidate. We can go further. What is the basis for assuming Brahmins as pure vegetarian when studies such as the one done by political economist Suraj Jacob and me show that at best only 66% Brahmins are vegetarian, a number that is certainly an overestimate given the political pressures to declare oneself as not-meat-eating?

Culturalization operates within a matrix of two other quintessential caste practices – essentialism and inherentism. While essentialism (which is a key mode of thinking for any stereotyping) assumes that a group has essential traits (for example, that Brahmins are essentially vegetarian), inherentism derives the identity of a particular individual from purported group traits (thus, for example assuming that an individual is Brahmin because she is vegetarian which is an essentialized trait of the group Brahmin). It is thus a vicious cycle – culturalization presents caste as culture, essentialism build a group based on essential cultural traits, and inherentism derives an individual’s identity from those very essentialized traits.

Indeed, we see this logic of inherentism, essentialism, and culturalization (or culturalism) at work in the most recent and egregious remarks by an elected legislator from the ruling party in Gujarat. This legislator was part of the BJP government-appointed committee of five ruling party members that remitted the life sentence of 11 convicted people who gang-raped and murdered Muslims during the Gujarat 2002 pogrom. After releasing the convicts he further absolved them by noting that “…Their families’ activities were very good; they are Brahmins. Their sanskar [values] are good.” Note how such logic makes the so-called values of Brahmins and their families derived from the fact that they are Brahmins by birth. It ‘naturalizes’ caste such that whatever Brahmins do, be it rape or murder, is justified or denied as needed. India, of course, has a long history of such legitimations of caste, the most relevant one here being the way that Bhanwari Devi’s rapists (who were dominant caste Gujjars) were acquitted in 1995.

Culturalization is the ‘merit’ argument of our times. It legitimizes caste relations and caste social order by representing a birth-based identity that is caste as if it is culture – which is a historically achieved, not naturally given, group capacity for meaningful living. Becoming aware of culturalization as a key legitimizing strategy of caste today, we have to understand that the politics of caste today needs progressives to view conflicts between caste groups as caste wars on cultural grounds, rather than cultural wars on caste grounds. The former view makes us aware that culture is used as the handmaiden of caste today and that culture is never coterminous with a social group. The latter view is focused on protecting caste-based culture, much like the khap panchayats. In a way, we need to remember that Ambedkar’s annihilation of caste was uncompromising – you cannot have caste as identity without having casteism.

Q: Now, it is true that anti-caste activism needs to be caste conscious (e.g., in the case of affirmative action.) Caste-conscious mobilization can take cultural forms, most clearly in the example of Dalit mobilization. How does what we discussed above bear upon that?

Yes. I have long written and spoken about the need for caste-conscious anticaste multicaste formations to combat caste. We need to be caste conscious in order to avoid the pitfalls of privileged caste caste-blindness or what is now theorized in the Indian context as castelessness (an assumption that caste is irrelevant to social life or life chances today). We need to follow Justice Blackmun who wrote in the famous Bakke case that “to get beyond racism we must first take account of race”. Caste conscious anticasteism means that we as activists are aware how caste operates in shaping our social relations and possibilities today. This of course also means that we are alert to culturalization as the latest form of caste legitimation. This also means that we acknowledge that caste is not simply a Dalit problem. As Anand Teltumbde said long time ago, “Castes cannot be annihilated by Dalits alone”. This means that we need a Dalit-led multicaste formation that is aware of the need to dismantle caste identities in a systematic and ethical manner (not just pretend they do not exist) while acknowledging caste-based inequalities. That is the challenge to anticaste activists and demands a view of caste as a relational reality.

Q: On the last point you raise and as a final takeaway, it is interesting to apply all the above lessons to define the caste system structurally. You argue that caste is a system of relations rather than a system of elements. Can you elaborate on that?

BN: As we’ve discussed above, a caste group is an assemblage of clans. But the assemblage is in the realm of imagination (as we discussed before, even if you’re privileged, you will typically only know 3 to 5 generations of your descent group.) A caste group is thus a fictionalized ‘thing’ and it becomes a reality because people begin feeling a sense of belonging which is real, and then they start acting on the sense of belonging and oppress others or monopolize power and wealth and prestige. That is a fact. Casteism is real, caste is fiction. Not unlike how we think about race as (biologically) unreal but racism as real. So, if you say caste is a social group, then we need to remind ourselves that it is a widely imagined social group. What I call, a fiction that has acquired the fixity of a fact.

But, I flip this way of thinking about caste groups as ‘things’. Instead of viewing castes as social groups, I look at castes as being created by, as produced by casteist social practices and social relations. Social groups like castes are then more like the nodes in a graph. The nodes are created by the lines. Where the line ends or meets another line, the node, i.e., the social group emerges. The lines are relations and practices. Practices are casteism. Casteism is real and produces caste. The line (relations and practices) produces the node (caste as groups). The reality is the line, not the node. It is a mistake to fixate on the node. What I described above is most famously captured by anthropologist Louis Dumont, who although very problematic in many ways, got some things right. What he got right in my view is that he looked at caste as a structure of relations. He said caste is “a system of relations, not a system of elements.”

Raghav Kaushik is a software engineer at Microsoft in Seattle and a social justice activist. Some of his recent engagements have been with the Kshama Sawant Solidarity Campaign, the fight against intellectual property protections applied to covid vaccines, and the fight against the authoritarian Modi regime in India.