Climate crisis takes its costs from gross domestic product. A recent study1 finds about a quarter of the countries studied are sensitive to such impact.

Climate crisis, negatively affecting economy in countries, takes toll; and it’s peoples that pay the toll while capitals, the dominant force creating climate crisis, reaps profit.

“[A] critical and still unresolved empirical question is”, the scientists conducting the study say, “whether temperature variation has a long-lasting effect on economic productivity and, therefore, whether damages compound over time in response to long-lived changes in temperature expected with climate change. Several studies have identified a relationship between temperature and gross domestic product (GDP), but empirical evidence as to the persistence of these effects is still weak.”

The study looked into issues related to the climate crisis and its impact on GDP.

The scientists said in the report:

“A large body of evidence now exists showing a relationship between temperature fluctuations and economic productivity. Temperature has been shown to influence output at global, national, and regional scales, affecting a wide range of sectors in both high-income and low-income countries. The persistence of these impacts has first-order implications for the magnitude of climate change damages: if temperature fluctuations affect the determinants of economic growth (e.g. depreciation of capital or the total factor productivity growth rate), then they have a persistent impact on the level of economic output. In this case, climate change damages are cumulative and may be orders of magnitude larger than currently represented in models used for the cost–benefit analysis of climate change, which mostly assume non-persistent damages (for example, when temperature variations affect the productivity of labor or capital) with a few recent exceptions.”

A number of fundamental questions related to people’s interest and the workers engaged with production come up with this statement: productivity, output at national, regional and global levels, growth, persistent impact on economic output/cumulative damage due to climate crisis.

They admit in the report: “A major empirical challenge is that estimating the sum of lagged effects, particularly for a non-linear function, can produce large standard errors and high uncertainty.” And they said: “[T]he uncertainty around this key question relevant to understanding the aggregate costs of climate change remains largely unresolved.”

The scientists made the same analysis using two alternative economic growth datasets spanning a longer time period: Annual data on economic growth of 43 countries from 1790 to 2009, developed to examine the persistence of macroeconomic shocks; and, another database that standardizes country-level GDP per capita for 170 countries for several centuries. Due to the sparsity of temperature and rainfall records pre-1900; they used only post-1900 data for both datasets. They used GDP data from the World Bank covering 217 countries from 1961 to 2017, and merged this dataset with population-weighted temperature and rainfall data from University of Delaware.

“[E]ffect of past temperature shocks on the future level of GDP,” the scientists said, “occurring because temperature affects the determinants of economic growth, that [they] refer to in this [study report] as ‘persistent’ impacts.”

They write:

“The question of persistence […] is distinct from this issue however. The distinction between persistent vs. non-persistent impacts arises because of how temperature affects the economy; non-persistent effects arise through temporary effects on productivity (crop yield losses from extreme heat are one example) whereas persistent effects arise from impacts on factors that have a long-lived effect on economic production (destruction of capital in extreme events for instance).”

The scientists said:

“The essence of the approach is that persistent and transient impacts on economic output can be distinguished using temperature variation occurring at different frequencies.”

And,

“Temperature variability at different timescales will produce distinct economic dynamics depending on the persistence of economic impacts.”

“The question of the persistence of climate damages is a”, the study report said, “first-order problem for climate change economics. Studies that allow climate change to affect the determinants of economic growth tend to produce far larger aggregate climate change costs than studies that impose only level effects on production. In response to the permanent shifts in temperature expected with climate change, persistent impacts operate via effects on the growth rate compound over time, producing far larger aggregate damages over the long time frames relevant for assessing climate change costs.”

The scientists found:

“[S]tatistically significant persistent temperature impacts on economic growth in 22% […] of the countries using the World Bank dataset. […] [T]he persistence of temperature impacts at least over the 15 year period […]”

“At the individual country level, only 15% (21%; 34%) of countries have effects that converge towards zero. For many more countries, the estimated effects either do not converge towards zero or intensify over time, an effect that could be due to adaptation or coping dynamics, competing growth and levels effects with different signs, or a reduction in attenuation bias with longer filter lengths […]. Pooling evidence from across all countries produces stable effect sizes with lower frequency variation for all three datasets, at least over the 10–15 year period. Therefore, the evidence suggests a sensitivity of aggregate economic output to temperature shocks persisting over at least the 10–15 year time frame and a conspicuous absence of evidence for fully non-persistent levels impacts.”

The scientists noted that their “approach [was] not able to distinguish between a levels effect that continues compounding over the 15 year time-frame of our lowest-frequency estimates but then subsequently reverses, and a ‘pure’ growth effect in which there is no subsequent reversal. Differentiating these two types of effects is a question of what happens in time-frames longer than 15 years, which is an inherently difficult empirical question due to the relatively short time span of data available. However, either interpretation of the filtered results (i.e. 15 years of continuously worsening levels effects followed by reversal or a fully persistent effect) implies persistence of damages over time periods longer than a decade. Either interpretation would imply larger aggregate climate damages than the standard approach to representing climate change costs in integrated assessment models, which assumes no persistence or compounding effects.”

Their “findings do not show strong evidence for the presence of only non-persistent impacts and instead suggest compounding effects over at least a decadal time frame. Therefore, restricting modeling of climate change damages to only non-persistent levels effects likely greatly under-states both the uncertainty and the downside risk associated with climate change.”

They find “evidence of persistent effects, implying temperature affects the determinants of economic growth, not just economic productivity. This, in turn, means that the aggregate effects of climate change on GDP may be far larger and far more uncertain than currently represented in integrated assessment models used to calculate the social cost of carbon.”

An earlier study used “historical fluctuations in temperature within countries to identify its effects on aggregate economic outcomes.” The scientists found “three primary results: First, higher temperatures substantially reduce economic growth in poor countries. Second, higher temperatures may reduce growth rates, not just the level of output. Third, higher temperatures have wide-ranging effects, reducing agricultural output, industrial output, and political stability. These findings inform debates over climate’s role in economic development and suggest the possibility of substantial negative impacts of higher temperatures on poor countries.”2

Another study found: “[C]limatic conditions can have a profound impact on the functioning of modern human societies, but effects on economic activity appear inconsistent. Fundamental productive elements of modern economies, such as workers and crops, exhibit highly non-linear responses to local temperature even in wealthy countries. In contrast, aggregate macroeconomic productivity of entire wealthy countries is reported not to respond to temperature, while poor countries respond only linearly. Resolving this conflict between micro and macro observations is critical to understanding the role of wealth in coupled human-natural systems and to anticipating the global impact of climate change.”3

The scientists “show that overall economic productivity is non-linear in temperature for all countries, with productivity peaking at an annual average temperature of 13 °C and declining strongly at higher temperatures. The relationship is globally generalizable, unchanged since 1960, and apparent for agricultural and non-agricultural activity in both rich and poor countries. These results provide the first evidence that economic activity in all regions is coupled to the global climate and establish a new empirical foundation for modeling economic loss in response to climate change, with important implications. If future adaptation mimics past adaptation, unmitigated warming is expected to reshape the global economy by reducing average global incomes roughly 23% by 2100 and widening global income inequality, relative to scenarios without climate change. In contrast to prior estimates, expected global losses are approximately linear in global mean temperature, with median losses many times larger than leading models indicate.”4

Another study said: “For centuries, thinkers have considered whether and how climatic conditions-such as temperature, rainfall, and violent storms-influence the nature of societies and the performance of economies. A multidisciplinary renaissance of quantitative empirical research is illuminating important linkages in the coupled climate-human system. We highlight key methodological innovations and results describing effects of climate on health, economics, conflict, migration, and demographics. Because of persistent “adaptation gaps,” current climate conditions continue to play a substantial role in shaping modern society, and future climate changes will likely have additional impact. For example, we compute that temperature depresses current U.S. maize yields by ~48%, warming since 1980 elevated conflict risk in Africa by ~11%, and future warming may slow global economic growth rates by ~0.28 percentage points per year. In general, we estimate that the economic and social burden of current climates tends to be comparable in magnitude to the additional projected impact caused by future anthropogenic climate changes. Overall, findings from this literature point to climate as an important influence on the historical evolution of the global economy, they should inform how we respond to modern climatic conditions, and they can guide how we predict the consequences of future climate changes.”5

A 2021 study found: “[T]otal climate damages are highly sensitive to the question of persistence”.6

Two other studies found: “[I]ncreases in summer and fall temperature could have persistent effects on the gross state product of US states.”7

In 2021, the Swiss Re Institute in its report – The economics of climate change: no action not an option – said:

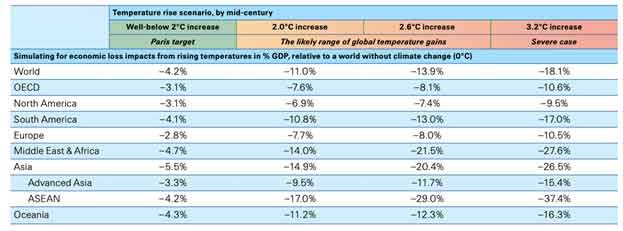

Climate change could wipe out 10% of the global economy’s total economic value by 2050, and this figure could rise significantly to 18% of GDP by mid-century if no action is taken and temperatures rise by 3.2°C. The hardest hit will be the Asian economies: 5.5% hit to GDP in the best-case scene, and 26.5% hit in a severe case scene, with regional variations – GDP losses of advanced Asian economies to be 3.3% in case of a below-2°C rise and 15.4% in a severe scene, and ASEAN countries to experience drop of 4.2% and 37.4% respectively, China losing nearly 24% of its GDP in a severe scene. The loss of Africa and the Middle East, will be 27.6% in a severe case scene, and 4.7% with temperature staying well below 2°C while the loss of Europe, in a severe case scene, will be 11%, and for the US, UK and Canada, it’ll be 10% (Table:1).

Table 1: World warming’s negative impact on GDP by mid-century by region

Source: SRI

The institute’s forecast was based on temperature increases persisting on the current trajectory and the Paris Agreement and net-zero emission targets are not met. The institute’s Climate Economics Index stress tests the way global warming will affect 48 countries that represent 90% of the world economy. The Index also ranks the countries’ climate resilience.

These findings, it shouldn’t be missed, are from, basically, market economy; and from within the world capitalist system. So, the questions of productivity, loss, etc. are to be viewed with that perspective. Loss due to climate crisis is now-a-days well-accepted by all concerned quarters, but a few deniers. [To be continued with parts II & III.]

Note:

- B A Bastien-Olvera, F Granella, F C Moore, 2022, “Persistent effect of temperature on GDP identified from lower frequency temperature variability”, Environmental Research Letters, 17 (8): 084038 DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac82c2

- Melissa Dell, Benjamin F. Jones and Benjamin A. Olken, “Temperature shocks and economic growth: Evidence from the last half century”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, vol. 4, no. 3, July 2012, DOI: 10.1257/mac.4.3.66

- Marshall Burke, Solomon M Hsiang and Edward Miguel, “Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production”, Nature, 2015 November 12; 527 (7577), DOI: 10.1038/nature15725

- ibid.

- Tamma A Carleton, Solomon M Hsiang, “Social and economic impacts of climate”, Science, 2016 September 9, 353(6304): aad9837, DOI: 10.1126/science.aad9837

- Newell R G, Prest B C and Sexton S E, 2021, “The GDP-temperature relationship: implications for climate change damages”, J. Environ. Econ. Manage., 1102445

- Deryugina T and Hsiang S, 2017, “The marginal product of climate”, report no.: w24072, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, p w24072, www.nber.org/papers/w24072.pdf; and Colacito R, Hoffmann B and Phan T, 2019, “Temperature and growth: a panel analysis of the United States”, J. Money Credit Bank, 51