Heatwaves will become so extreme in certain regions of the world within decades that human life there will be unsustainable, the United Nations and the Red Cross said in a report on Monday.

Heatwaves are predicted to “exceed human physiological and social limits” in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and south and southwest Asia, with extreme events triggering “large-scale suffering and loss of life”, the organizations said.

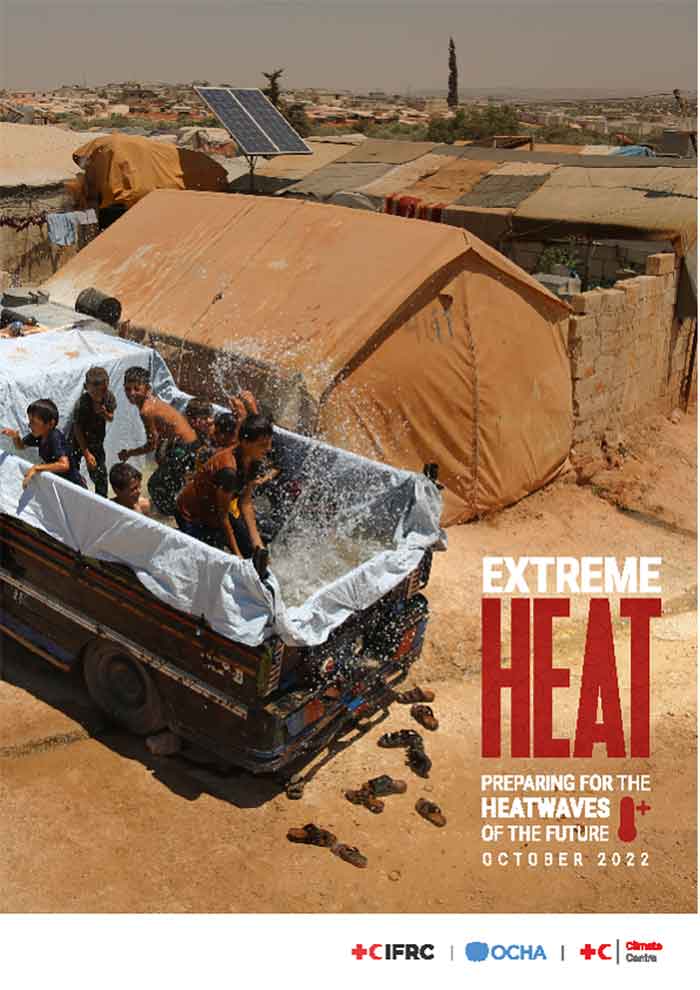

Heatwave catastrophes this year in countries like Somalia and Pakistan foreshadow a future with deadlier, more frequent, and more intense heat-related humanitarian emergencies, they warned in Extreme Heat: Preparing for the Heatwaves of the Future ( https://www.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/Extreme-Heat-Report-IFRC-OCHA-2022.pdf), a joint report.

The report revealed that 38 heat waves accounted for the deaths of more than 70,000 people worldwide from 2010 to 2019 — a likely underestimate of the real toll — on top of the fallout on lives and livelihoods.

They cite figures that Bangladesh, for example, experienced as much as a 20% increase in deaths on heat wave days compared with an average day.

The report said:

An extreme-heat event that would have occurred once in 50 years in a climate without human influence is now nearly five times as likely. Under 2°C of warming, an extreme-heat event is projected to be nearly 14 times as likely and to bring heat and humidity levels that are far more dangerous.

Earlier this year, Indian capital city Delhi witnessed severe heatwaves in the summer months between April and June, with mercury soaring to as high as 49 degree celsius. Adjoining Indian states of Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Punjab, and Bihar also witnessed soaring temperatures, which prompted Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to flag the increased risk of fires due to rising temperatures.

The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) released the report in advance of next month’s COP27 climate change summit in Egypt.

The report said: Heat waves can drive people to flee their hot homelands — adding to migration to cooler countries.

“We do not want to dramatize it, but clearly the data shows that it does lead towards a very bleak future,” said IFRC secretary-general Jagan Chapagain.

They said aggressive steps needed to be taken immediately to avert potentially recurrent heat disasters, listing steps that could mitigate the worst effects of extreme heat.

Limits Of Survival

“There are clear limits beyond which people exposed to extreme heat and humidity cannot survive,” the report said.

“There are also likely to be levels of extreme heat beyond which societies may find it practically impossible to deliver effective adaptation for all.

“On current trajectories, heatwaves could meet and exceed these physiological and social limits in the coming decades, including in regions such as the Sahel and south and southwest Asia.”

It warned that the impact of this would be “large-scale suffering and loss of life, population movements and further entrenched inequality.”

The report said extreme heat was a “silent killer”, claiming thousands of lives each year as the deadliest weather-related hazard — and the dangers were set to grow at an “alarming rate” due to climate change.

According to a study, the number of poor people living in extreme heat conditions in urban areas will jump by 700 percent by 2050, particularly in west Africa and southeast Asia.

“Projected future death rates from extreme heat are staggeringly high — comparable in magnitude by the end of the century to all cancers or all infectious diseases — and staggeringly unequal,” the report said.

Unequal Impacts

The report said:

The impacts of extreme heat are hugely unequal in both social and geographic terms. In a heatwave, the most vulnerable and marginalized people, including casual laborers, agricultural workers, and migrants, are pushed to the front lines. The elderly, children, and pregnant and breastfeeding women are at higher risk of illness and death associated with high ambient temperatures.

It said:

Cities are at the epicenter of vulnerability to heatwaves. Informal and off-grid settlements, which share many characteristics with camps in humanitarian settings, are at particularly high risk. Analysts project a 700 per cent global increase in the number of urban poor people living in extreme-heat conditions by the 2050s. The largest increases are expected in West Africa and South-East Asia.

Loneliest Disaster

The report said:

- The impacts of heatwaves are dreadfully familiar to humanitarians. They can overwhelm hospitals, leave people desperate for clean water and reduce families to one meal a day. But while heatwaves can be every bit as deadly as other emergencies, they have a spatial and social footprint that sets them apart.

- There is a unique geography to a heat emergency that can confound traditional ways of thinking in the humanitarian sector. City maps that record deaths in a heatwave reveal a familiar pattern: concentrated, to be sure, in poor and marginalized areas. But within those areas, the victims are dispersed. Rather than the focused devastation of an attack on a marketplace or the landfall of a typhoon, the impact is scattered. Instead of a hundred people on one block, a heatwave kills a few people on each block. A hundred people suffering together but disconnected.

- In this sense, heatwaves also have a unique sociology. They are the loneliest disaster.

- Their first victims are often the socially and physically isolated. In a manner similar to COVID-19, heatwaves expose and prey on the inequalities in a community. Even when the risks of extreme heat are understood, construction workers, farmers and homemakers have no choice but to expose themselves to that heat. And even if cooling options are effective and available, many people lack the resources to access them. In a heatwave, the economically insecure are pushed to the front lines. The first to die at home are the elderly, the lonely and the sick.

“As the climate crisis goes unchecked, extreme weather events, such as heatwaves and floods, are hitting the most vulnerable people the hardest,” said UN humanitarian chief Martin Griffiths.

“The humanitarian system is not equipped to handle crisis of this scale on our own.”

Unimaginable

Chapagain urged countries at COP27 to invest in climate adaptation and mitigation in the regions most at risk.

OCHA and the IFRC suggested five main steps to help combat the impact of extreme heatwaves, including providing early information to help people and authorities react in time, and finding new ways of financing local-level action.

They also included humanitarian organizations testing more “thermally-appropriate” emergency shelter and “cooling centers”, while getting communities to alter their development planning to take account of likely extreme heat impacts.

OCHA and the IFRC said there were limits to extreme heat adaptation measures.

Some, such as increasing energy-intensive air conditioning, are costly, environmentally unsustainable and contribute themselves to climate change.

If emissions of the greenhouse gases which cause climate change are not aggressively reduced, the world will face “previously unimaginable levels of extreme heat”.

Five Things To Know

The report mentioned the following five points to know:

- Heatwaves are a major cause of suffering and death.

- Heatwaves prey on inequality. Their greatest impacts are on vulnerable, isolated and marginalized people.

- Climate change is already making heatwaves much more dangerous.

- 4. Heatwaves will become deadlier with every further increment of temperature rise associated with climate change.

- Extreme heat has cascading impacts, threatening nonhuman life and undermining the systems that keep people healthy and alive.

England’s heatwaves see Highest Ever Excess Deaths Among Elderly

An earlier Reuters report said:

England saw the highest excess mortality figure from heatwaves this year since records began in 2004, health officials said on Friday, after a hot summer that saw temperatures rise to all-time highs.

England recorded 2,803 excess deaths among those aged 65 and over during summer heatwaves this year, possibly due to complications arising from extreme heat, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) said in a statement. The figures exclude deaths from COVID-19.

“These estimates show clearly that high temperatures can lead to premature death for those who are vulnerable,” UKHSA Chief Scientific Officer Isabel Oliver said.

“Prolonged periods of hot weather are a particular risk for elderly people, those with heart and lung conditions or people who are unable to keep themselves cool such as people with learning disabilities and Alzheimer’s disease.”

Britain recorded its highest ever temperature, of just above 40 Celsius in eastern England on July 19.

The heatwave, which caused fires across large grass areas, destroyed property and pressured transport infrastructure, had been made at least 10 times more likely because of climate change, scientists said.

Around 1,000 excess deaths were recorded among those over 65 between July 17-20, the UKHSA said, while the Aug. 8-17 period recorded an estimated 1,458 excess deaths.

Statisticians use “excess deaths” — a term that became more commonplace during the coronavirus pandemic — to describe the number of fatalities in excess of normally observed mortality numbers for a particular time of year.

Despite peaks in mortality during heatwaves, the majority of days in the winter usually show a higher number of deaths than in the summer, ONS Head of Mortality Analysis Sarah Caul said.

California Does Not Know How Many People Died In Record Summer Heatwave

A Los Angeles Times report said:

It was the worst California heat wave ever recorded in September — an epic grilling that disabled one of Twitter’s main data centers, pushed the power grid to its limit and triggered a succession of weather and safety alerts.

For 10 grueling days, meteorologists tracked record-setting temperatures as they boiled across the state — 116 degrees in Sacramento, 114 in Napa, 109 in Long Beach. But for all the data on soaring temperatures, there was little information on the heat wave’s human toll, or how many people had been sickened or even killed.

The state’s ongoing struggle to account for heat wave illnesses and deaths — despite promises to improve monitoring — has frustrated some public health experts who say the lack of timely information puts lives in jeopardy.

“We are not respecting the most important natural disaster that we do get,” said David Eisenman, co-director of the UCLA Center for Public Health and Disasters. “We are not really giving it the attention it deserves, and the state releasing data is not some abstract thing — people need to know how harmful it was if they’re going to start to respect it.”

Last year, a Los Angeles Times investigation found that California has chronically underestimated heat fatalities even as heat waves become more frequent and more deadly. Although the Legislature recently agreed to the creation of what is known as a syndromic surveillance system, which will collect real-time data from emergency departments, it remains unclear when such a network will become operational statewide.

Currently, the California Department of Public Health said it tracks heat-related illnesses and deaths “using data sets that are available at approximately a 6- to 18-month lag time,” due in part to how long it takes to certify deaths as being heat-related. As a result, they were unable to provide any numbers for illnesses or deaths due to the recent heat wave.

The department also said it was “still assessing the landscape for the implementation of statewide syndromic surveillance,” and did not yet have a time frame for when that system would be online.

Los Angeles-area officials were able to provide only slightly more information than the state.

In response to a public records request, the L.A. County Department of Health Services, which operates county hospitals and the Emergency Medical Services agency, said fire departments responded to 146 calls classified as “heat” — defined by the agency as environmental hyperthermia — during the 10-day period of Aug. 31 to Sept. 9. There were only 10 such calls in the prior 10-day period.

The county’s Department of Public Health also reported a sevenfold increase in the percentage of emergency department encounters classified as heat-related illnesses during Labor Day weekend, Sept. 3-5, compared to the entire month of August. It said the estimate should be viewed with caution, however, because it was based on a small number of heat-related illness reports — only 81 out of more than 9,100 emergency department encounters on the peak temperature day of Sept. 4.

For its part, the L.A. County coroner’s office ran a query into heat-related deaths during the peak heat days of Aug. 31 to Sept. 5 and said it “did not come up with any.”

While it is possible that there was minimal death and illness caused by the heat wave, it is unlikely, Eisenman said. His own team’s analysis predicts that there are at least eight extra deaths per day in Los Angeles County during extreme heat events, with that number increasing to 10 or more as heat waves wear on.

“This was a long one and it was pretty severe, and we haven’t done enough in Los Angeles or California to have prevented deaths, to have mitigated the harms,” he said. “We have no reason to think that we’re avoiding death with something that is known to cause the most amount of harm of all weather events.”

Unlike other natural disasters such as hurricanes, extreme heat “comes and goes invisibly,” Eisenman said. That can make it difficult to adequately communicate its dangers. But extreme heat events are also increasing in severity and length in California, and it is critical for people to understand the threat.

He noted that after the brutal Pacific Northwest heat wave of 2021, officials in Oregon, Washington and the Canadian province of British Columbia reported information on heat-related illnesses and deaths within days — which was not the case in California after the heat wave last month. What’s more, health departments in the state have been releasing COVID-19 data daily during the pandemic, so they do have the capability to track information in real time.

Among those most vulnerable to extreme heat are children, the elderly, homeless people and pregnant women. Farmworkers, construction workers and factory workers are also at risk, as are people with underlying health conditions such as kidney disease and diabetes, which can make their bodies less able to handle dehydration and heat, Eisenman said.

Part of the difficulty in tabulating heat deaths, according to state and local health officials, is that “heat” is not coded on death certificates. Because of this, a person who dies from a heart attack while suffering from heat-related illness, for example, may be recorded as dying from the heart attack.

Under such circumstances, the only way to determine the number of heat fatalities during a given heat wave would be to perform an “excess deaths” analysis, where the number of deaths that occurred during a heat event is compared with the number of deaths that occur under normal conditions. However, such an analysis requires a sufficient amount of time to have elapsed since the heat wave — “at least several months,” the Los Angeles County Health Department said.

The department does have its own syndromic surveillance system, but said it would not release that data publicly because the system collects only limited information on patients’ complaints during emergency department visits. As a result, “there can be significant underreporting and misclassification of health conditions,” it said.

Jonathan Parfrey, executive director of the group Climate Resolve, said he could understand why the county would not want to release imperfect data, but that not doing so was a mistake.

“They are missing the forest for the trees,” he said. “There is the big picture reality — there are many more hospitalizations and emergency room visits and incidents of deaths during heat events, and the public does not know this. And so if it’s off by 5% or 10%, that’s not the point. The point is that there is a significant impact on public health during extreme heat events.”

Paul English, director of Tracking California for the Public Health Institute, agreed. He said officials must conduct such an analysis for the last heat wave.

“Did the state do enough? Well, we need to get the data,” English said. “Are they going to look at the excess mortality and morbidity and get the true picture of how people were affected? They just need to run that analysis, and I hope they do it, and publicize it so we know the full impact.”

While California is still struggling with data on heat illnesses and death, state and local officials said they took immediate action to respond to the September heat wave.

The state Department of Public Health said one of its top priorities was “to get the word out for people to be aware of the health risks of extreme heat,” including negative health outcomes and the threat of potentially concurrent wildfires. In particular, the agency said it focused on providing guidance to local health jurisdictions, schools, first responders and others working to protect the most vulnerable, and worked with other state agencies to disseminate information.

The agency said it also updated its extreme heat website with new guidance and added a “Flex Alert banner” to its homepage, posted public service announcements in Spanish and English on social media, provided communication resources for local health jurisdictions and shared safety tips about wildfire smoke and ash, among other actions.

However, English noted that his own team has encountered far more than two languages while working on air pollution issues affecting farmworkers.

“They need to be able to get this messaging in a culturally appropriate way,” he said, and “those type of alert systems don’t really exist for those specialized populations.”

Experts this year were also hoping for the passage of Assembly Bill 2076, a measure that would have established a chief heat officer for the state and mandated the coordination of more than a dozen state agencies. The bill died in committee in the Senate.

“We still do not have a comprehensive approach to dealing with extreme heat in the state — it is still fragmented and piecemeal, and that is an issue,” said Enrique Huerta, legislative director for Climate Resolve.

There have been some successful efforts to address extreme heat, however, including the passage of Assembly Bill 2238, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in September, which will establish a statewide warning and ranking system for extreme heat events by 2025.

Also passed last month were AB 2420, which will review research on extreme heat among pregnant women, and Senate Bill 852, to allow for the creation of climate resilience districts for investing in infrastructure that mitigates heat and other climate impacts. Los Angeles this year also named its first chief heat officer, Marta Segura, who has been tasked with improving the city’s preparation and response.

Huerta noted that the state last year budgeted $400 million for extreme heat, including $300 million for climate resiliency. He hoped the spending would focus less on long-term mitigation and more on “solutions that can be done tomorrow,” such as cool pavement installation to immediately reduce ambient temperatures for the most imperiled residents.

“If that money is managed and administered effectively, it can go a long way to reduce heat illness and death,” Huerta said.

But September’s heat wave came and went with few of those ambitious bills, projects or tracking systems off the ground, and UCLA’s Eisenman said the sense of urgency has never been greater.

“If the numbers are what we think they are — at least 10 extra deaths per day in L.A. County — a portion of those are preventable if we start to get those programs up and running,” he said.