The term `Concentration Camps’ was used to describe the notorious prisons run by the Nazis in the 1930-40 period in Dachau, Buchenwald, Auschwitz and other places in Germany, and occupied territories in Europe. The plight of the prisoners who were held there had been well documented by later researchers who delved into the records of those camps and interviewed the survivors. Their findings revealed that the main targets of the Nazi regime were the minority Jewish community, political opponents and intellectual dissidents. They were picked up and kept confined within the walls of these so-called `camps’, where they died – from tortures, denial of medical treatment, or suffocation in gas chambers.

New replicas of Nazi-era Concentration Camps have emerged in what is claimed to be the world’s largest democracy. The Indian government has officially acknowledged that at least 4,484 people died in police custody during 2000-2020. This was revealed by the Union Minister of State for Home Affairs, Nityanand Rai in the Lok Sabha on July 26, 2022 , in response to a question. Incidentally, the highest number of such custodial deaths was reported from UP – a state ruled by the BJP. Even before that, the NHRC (National Human Rights Commission) in its annual report of 2020 had listed some 17,000 people who died in police and judicial custodies during that year. The latest report of the National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB) reveals that 88 custodial deaths happened in 2021, the highest number reported from Gujarat – a state incidentally ruled by the BJP – echoing the record of prison deaths in BJP-ruled UP !

Police custody and judicial custody

For readers who may not know the separation between the two types of custodies, let me explain the difference – which is mere terminological, since both result in the same plight for the prisoners. Persons who are arrested on any charge are instantly taken to the local police station (or `thana’), where they are incarcerated in a cell that is attached to the office premises. The tiny cell is barred by a metal grill, which is opened only to allow meals to the incarcerated persons. During this stay in the police custody, the prisoners are subjected to `grilling’ (a term ironically enough sounding like `grill’ which they face within the cell). It means interrogation by the police intelligence agencies, often accompanied by physical torture (euphemistically described as `third degree methods’) in order to extract confessions from the prisoners to admit to crimes that they may not have committed. But these forced confessions enable the police to justify their arrest and demand their imprisonment. The lower courts also, without corroborating the authenticity of these so-called confessions, sentence them to imprisonment.

The prisoners are then transferred from `police custody’ to `judicial custody’ – a term to describe jails. Here they are incarcerated under two categories – as (i) under-trial prisoners (pending sentences from courts), and (ii) convicts already sentenced by courts to serve a certain period of imprisonment. But in these jails also, the prisoners continue to suffer from the same plight that they underwent in police station cells. They continue to be tortured by a new set of guards – the jail wardens, who beat them up on the slightest pretext. Their daily staple are contaminated drinking water, undercooked food and stale leftovers from the previous day. When they fall ill as a result, they are denied medical treatment. Most of the custodial deaths reported by the NHRC are due to malnutrition of the prisoners, infections from unhygienic jail conditions and lack of timely medical attention.

Deaths in jails – killings through ill-treatment

While the majority of these deaths in judicial custody goes unreported in the media due to their obscure origins, some of these cases have recently attracted public attention because the victims of such deliberate ill-treatment are well-known social activists who are incarcerated on false charges. Among them was the late octogenarian Father Stan Swamy, who was kept imprisoned in Taloja Central jail in Maharashtra for years, and despite complaints of ill-health, he was denied medical attention till he reached the extreme stage, when he was transferred to a hospital where he died on July 5, 2021.

Soon after, Pandu Narote, an Adivasi peasant activist who was imprisoned in Nagpur Central Jail, died on August 25. According to reports, he was ill, and despite repeated requests for hospitalization, the jail authorities refused permission. Pandu Narote was a co-accused with another well-known social activist – G. N. Saibaba, former professor of Jawaharlal Nehru University of Delhi, who is undergoing life imprisonment in the same Nagpur Central Jail for his alleged Maoist links. The wheel chair bound professor has been medically certified as 90% physically challenged. Yet he has been incarcerated within the confines of a narrow circular cell (called `anda cell’ because of its similarity with the interior of an egg). The jail authorities also require him to clean his own cell. They are literally driving him to share the fatal end of Father Stan Swamy, and his co-accused Pandu Narote, among many other victims of the Indian prison system.

Among other disabled political prisoners who still manage to stay alive in these cells like G. N. Saibaba, is the student leader Atiq-Ur-Rehman who is in a jail in UP, while suffering from partial paralysis and after effects of a heart surgery. Other prisoners from the notorious Taloja jail and several prisons have been complaining about the inhuman conditions that they live in and the lack of medical facilities when they fall ill.

Tales of survivors

Some of the prisoners – both political and non-political – after their release, have recounted the experiences they went through behind the bars. They give us blow-by-blow accounts of the horrible living conditions in Indian jails, where the inmates are also subjected to physical torture by jail wardens. But their narratives also bear testimony to their fighting spirit. Even in those deadly environs of the jails, they mustered their innermost strength not only to survive, but also to mount protests against unjust acts of the jail authorities.

Let me draw the attention of readers to some of the chronicles by the survivors – which often eerily resemble the experiences undergone by their predecessors from the Nazi Concentration Camps. In the 1970s, one of the many victims of the Indian prison system was Ramchandra Singh, barely twenty years old, who was thrust into Hardoi District Jail in Uttar Pradesh in September, 1970 – accused of Naxalite activities. During his 13-year incarceration (all through his transportation from Hardoi to Unnao, and then to Fatehgarh Central Jail), he managed to smuggle out his secret diary of his daily experiences, written in Hindi, with the help of friends. It was first serialized in the journal Rashtriya Sahara in 1984. Its English translation by Madhu Singh came out in 2018, under the title: 13 Years: A Naxalite’s Prison Diary. Here is a quote from the book, where Ramchandra Singh narrates how prisoners were tortured : “… the barbarous tortures inflicted upon inmates in solitary confinement was enough to make the cruellest of the inmates shudder with fear. Throughout the day one could hear the victims howling with pain.”

Another chronicle reveals the plight of women prisoners in Indian jails. A Kashmiri Muslim woman Anjum Zamarud Habib was arrested on 6 February, 2003, under POTA (Prevention of Terrorism Act) and was sent to Tihar central jail in Delhi, where she spent five years till her release in December 2007. After her release, she recounted her experiences in Tihar jail in a book written in Urdu – which was translated by Sahba Husain into English and published in 2011 under the title: Prisoner No. 100 : An Account of My Nights and Days in an Indian Prison. Here she remembers “the dark and terrifying images from the jail (that) would come alive..” During an interview with her some years after her release, in Srinagar, Sahba Husain broached the topic of sexualized violence against women prisoners, and whether she knew about it. . Anjum Zamarud Habib said: “Yes, I am well aware that this happens both during interrogation and in jail…”

Apart from those who were released after serving prison terms following conviction (usually on false charges), there were others who spent long years in jail held on charges of terrorism – to be eventually found innocent and were acquitted by the courts after their long ordeal. But such acquittals could be made possible only after a long time-consuming and expensive judicial process that was pursued by their families or human rights activists, who approached the various courts, from bottom to top, to prove their innocence. In the meantime, these innocent young people lost some of the most precious years of their lives, having been kept behind bars.

Among the written testimonies by these victims of the Indian state’s systematic persecution of innocent people and their treatment in jails, two books deserve world-wide attention. The first is entitled: Framed, Damned, Acquitted. Dossiers of a `Very’ Special Jail, published in 2012 by the Jamia Teachers’ Solidarity Association of Delhi. It documents 16 cases of imprisonment of young Muslims accused of terrorism by the police, who after spending years in prison were declared innocent and acquitted by the courts only in 2012. The second book, published recently, is jointly written by social activist Dr. Aleemullah Khan and journalist Manisha Bhalla, entitled: Baizzat Bari ? (translated as `Acquitted with Honour’). It describes the ordeals of 16 young Muslim men, who were arrested around 2001, again on the same charge of terrorism. After spending some twenty years in prison, they were recently found to be innocent by the courts which acquitted them. The book is based on interviews with the acquitted people, who tell us about the devastation that was wreaked upon their lives at the prime of their youth. They have now turned into broken middle-aged men, struggling to piece together their families and tide over financial woes.

Atrocious role of the Indian judiciary

Apart from the revelations of the inhuman conditions in Indian jails, these testimonies of the survivors also expose the irresponsible role of the judges who initially sent these innocent people to jails, without corroborating facts and relying solely on framed up charges by the police. It took years for the victims to approach the higher courts, which overturned the verdicts passed on them by these judges of the lower courts, and acquitted them.

Shouldn’t these judges who sent them to prison, and who were eventually found to be wrong in accusing them, be hauled up for accountability, and if necessary, prosecution ? Shouldn’t they be held responsible for ruining the .. lives of hundreds of young people ? Shouldn’t they be asked to compensate them who were victims of their irresponsible judgments ?

But what is shocking that even after the exposure of these erroneous judgments by courts that led to the incarceration of innocent people inside oppressive and unhealthy police and jail custodies, today the judges starting from the lower courts to the apex court, continue to sanction the incarceration of prisoners in these same custodies. They refuse to grant bail even to those suffering from serious ailments, as some prisoners of Taloja Central Jail arrested in connection with the infamous Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case – on false charges.

Shouldn’t the judge who delayed bail to Father Stan Swamy for medical treatment, be hauled up for illegal behaviour that led to his death ? Shouldn’t he be ex-communicated by the judicial community ?

Need for accountability by Indian judges

There are international precedents of demanding accountability from judges for their erroneous acts – which often amount to criminality. In Germany, soon after the defeat of the Nazi regime, an international court was set up in Nuremberg for the trial of war criminals. Among the accused were four German judges, who faced charges of using their positions to approve of the Nazi regime’s sterilization and cleansing policies (directed against Jews). Nearly two decades later, that trial was immortalized in a film based on the testimonies of both the prosecutors and the accused judges. Entitled: `Judgment at Nuremberg,’ it was made in 1961, directed by Stanley Kramer, starring Spencer Tracy, Marlene Dietrich and Burt Lancaster among other famous actors.

May I request our judges in India to watch this film, and try to salvage from their conscience whatever little residues may be left of the judicial impartiality that they swore by when they entered their profession ? Shouldn’t they be ashamed of collaborating with a neo-Nazi regime in India by selectively sentencing Muslim youth, social activists and political dissidents – just as their German predecessors in 1930-40 did by targeting Jewish minorities, dissident intellectuals and political opponents ? Are they prepared to face queries about their judicial integrity before an international court ?

Special Cell of Delhi Police – modelled on the Nazi pattern

Quite often, some of these judges delivered their verdicts based on evidence provided by an agency called `Special Cell of Delhi Police.’ According to its terms of operation, this cell is required to ‘prevent, detect and investigate cases of terrorism, organized crime and other serious crimes in Delhi.’ How has this cell been functioning from its Lodhi Road office ?

From the published memoirs of survivors from police and jail custodies, as quoted above, it is this cell that emerges as a notorious chamber of horror -mentioned every time by them when recounting their experiences. It is here that the arrested persons were taken into, subjected to grilling and physical torture, and later to be sent to jail charged with heinous crimes.

Anjum Zamarul Habib describes her plight in her above-mentioned book Prisoner 100 : An Account of My Nights and Days in an Indian Prison. On February 6, 2003, she took a taxi in Delhi’s Chanakyapuri area – the diplomatic enclave which houses the foreign embassies. “As soon as I crossed Nehru Park,” she writes: “my taxi was suddenly surrounded by other vehicles and I was asked to step out. The taxi was searched….(by an Intelligence Bureau team) … I was searched personally and asked to step into another car. I objected strongly, but just then two other cars, with loud sirens wailing, approached and an IB (Intelligence Branch) woman officer, sitting in a big white car, forced me into her car and took me to the Special Cell of the Delhi Police at Lodhi Road.” Here an “intense interrogation began that continued through the night…The (police) officers used derogatory language….and this is what one of them said to me, ‘Begum Sahiba…we will strip you, take your pictures, print posters and put them up all over the country, you will not be able to ever step out again.’”

This notorious Special Cell framed innocent youth, and fabricated evidence against them, to persuade gullible judges at the lower courts to send them to jail. Some among them were lucky to get acquitted by a few judges at the higher courts, who were discerning enough to find them innocent – although after years of incarceration. Their plight is described in the above mentioned book Framed, Damned, Acquitted. The sub-title Dossiers of a `Very’ Special Cell, draws our attention to the nefarious role played by this police intelligence outfit in framing them.

Echoes from the Nazi era

The accounts of ill-treatment of prisoners in Indian police cells and jails, as recounted by those who survived physical and mental tortures, sound like eerie echoes from the concentration camps of Buchenwald, Auschwitz and Dachau of the Nazi era. It is almost hundred years now since atrocities were carried out in secrecy by the Nazi regime in the `concentration camps.’ Although condemned world wide, those same Nazi-style punitive measures are being adopted by the present Indian state – behind the walls of its police stations and jails.

In Nazi Germany, those who were put inside the `concentration camps’ were members of the religious Jewish minority, along with German political opponents (like the Communist leader Ernst Thalmann, who was shot dead in Buchenwald) and dissident intellectuals (like Sebastian Nefzger, a Munich school teacher, killed in Dachau). Some among them were sent to gas chambers where they were suffocated to death.

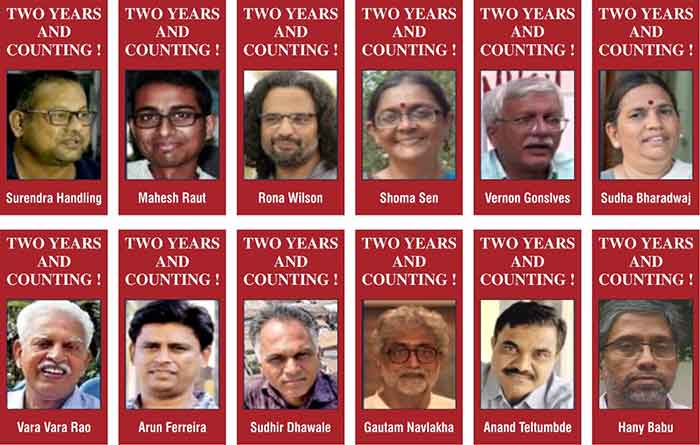

In a parallel move, the Indian state today has detained in police custody and jails, members of the religious Muslim minority, political opponents (like Varavara Rao and G.N. Saibaba), and dissident intellectuals (like Gautam Navlakha and Vernon Gonsalvez). They are facing a similar threat of extermination, that the prisoners of the Nazi concentration camps faced in the past. Along with physical tortures, they are subjected to the non-violent process of slow-poisoning – polluted drinking water, sub-standard food, denial of medical treatment when they fall ill – which all threaten their lives.

Indian state’s violation of UN regulations

But concerns over these cases of oppression and killings of prisoners in India are not confined only within the borders of India, but extend to the global arena, where reputed international organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have been coming out with annual reports damning the Indian state for its atrocious treatment of prisoners, and failure to adhere to UN codes.

To go back to these UN codes, they were formulated after the defeat of Germany in World War II, and following the revelations of atrocities by the Nazi regime against prisoners. At the end of years of efforts by world political leaders and champions of human rights to prevent recurrence of ill- treatment of prisoners, and following a consensus among them, the United Nations on December 10, 1984 adopted the historic UNCAT (UN Convention against Torture) which included under its provisions, `other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.’

Curiously enough, although the Indian government signed this Convention, it refused to ratify it – thus avoiding the requirement to implement its recommendations. During the last four decades since the adoption of UNCAT, New Delhi whether under the Congress, or the UPA or the BJP regime, had remained consistent in refusing to ratify it. There are enough grounds of suspicion that the Indian state by its refusal, is preventing scrutiny from the UN into its own atrocious record of ill-treatment of prisoners.

There is also another UN resolution called UN Standard Minimum Rules for the treatment of Prisoners, which was adopted in 2015. It is also known as Nelson Mandela Rules (in memory of the South African leader who suffered more than twenty years of ill-treatment in notorious prisons like Robben Island and Polsmoor Prison from 1964 till 1988). Under these rules: “All prisoners shall be treated with the respect due to their inherent dignity and value as human beings. No prisoner shall be subjected to, and all prisoners shall be protected from, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, for which no circumstances whatsoever may be invoked as a justification.”

How can the Indian state be compelled to adhere to these UN conventions ?

Sumanta Banerjee is a political commentator and writer, is the author of In The Wake of Naxalbari’ (1980 and 2008); The Parlour and the Streets: Elite and Popular Culture in Nineteenth Century Calcutta (1989) and ‘Memoirs of Roads: Calcutta from Colonial Urbanization to Global Modernization.’ (2016).