We are celebrating yet another Gandhi Jayanti. Given the significance that Mahatma Gandhi holds not only for Indians but globally, some introspection about the current state of affairs in India and Gandhi’s philosophy as a possible antidote to rapidly increasing hatred and violence is urgently required.

Let me begin by using Dharma as an example. The contemporary fallacy of collapsing dharma into mere religion is part of the problem. Hindutva misuses the concept of ‘Dharma’ and ‘Ram Rajya.’ Ram Rajya, technically and in Gandhian terms, would mean a state/regime where justice reigns supreme, where the most marginalised are taken care of without discrimination. The image of Lord Rama enjoying half-eaten fruit from Sabri displays not only his magnanimity but outreach. He did not seek vengeance for being banished to the forests but instead took the suffering as his duty. Politicians in India often resort to insincere caricaturing of Rama as their political project but overlook the qualitative difference between his politics of suffering and their politics of making others suffer.

During his lifetime, Gandhi’s constant efforts to reach out to the diverse cultural and religious spectrum in India stand testimony to his belief in upholding and sustaining democratic discourse. His difficult conversations, both in the form of debates and discussions, with stalwarts like Mohammed Ali Jinnah, B.R. Ambedkar, Jawaharlal Nehru, various leaders of the working class, and on some occasions, even V.D. Savarkar, are proof of it.

Now let me turn to more significant aspects of his philosophy. Satya (truth) and Ahimsa (non-violence) as the foundation of an ethical political practice are the most potent contributions of Gandhian thought. It is within this framework that Satyaghara (to insist on truth) opens up a wild and positive possibility for democracy. It infuses democracy with unimaginable vigour because it insists on speaking truth to power. Power here becomes an object of suspicion. Power to do something and power over something/someone only in the light of satya and ahimsa creates ethical boundaries for authority here but also endless possibilities for justice. If the action or thought is untruthful, it is illegitimate. The idea is quite different to what liberal democratic tradition would suggest while investing unbridled power in the notion of state and also legitimising certain state acts if they justify the preservation of the state or legal order. Gandhi consistently challenged the western conception of legal order, sovereignty, and citizenship. For him, ethics must be the premise of legal order, upholding of truth and justice is the duty of power and authority, and practice of truth and non-violence is the discourse of citizenship. If all this comes together, then there is the emergence of the utopia called Ram Rajya. Hindutva’s deliberate misuse of Rama has created difficulties for ‘others’ to engage with the discourse around Ramrajya. However, boldness is required to wrest it back as a meaningful concept that can prove meaningful for a plural democracy like India. Ramrajya can also be understood as a utopia, given the cultural context of India, which could be utilised to intensify the fight for justice and against marginalisation.

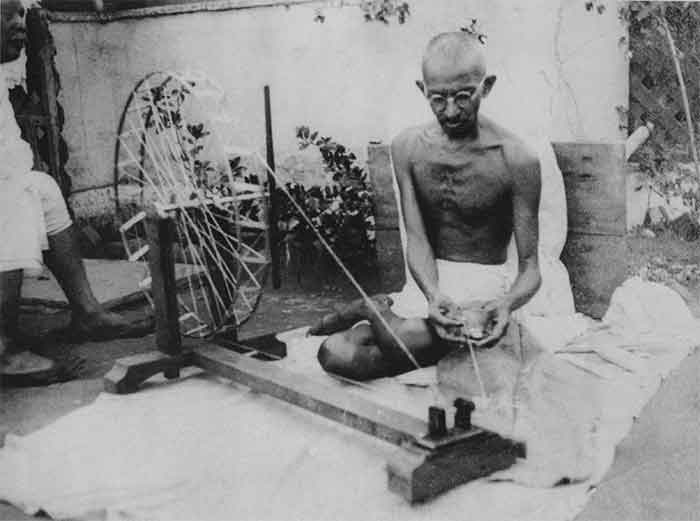

Another vital contribution of Gandhi’s thought is the concept of Swaraj. Recently, 75 years of Indian independence were celebrated with great pomp and show under the theme ‘Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav.’ However, we need to ask ourselves- what is it that we are celebrating? Was independence merely the transfer of power from the British to the Indian elite, or is it something much more meaningful? Gandhi’s Swaraj facilitates course correction in this regard by reminding us of the true meaning of independence. If 75 years of Indian independence is evaluated on the scale of Gandhian swaraj, I am afraid we have failed miserably. Using Gandhi as a showpiece and celebrating the significance of his powerful ideas are two diametrically opposite intentions. Unfortunately, we are more interested in the former than the latter. The entire campaign of ‘Make in India’ grossly undermines the campaign for swadeshi. Becoming a cog in the wheel of global capitalism and hunting for your pound of economic flesh is different from Gandhian self-reliance. One can argue that Gandhi’s concept of Swaraj invests political praxis with a commitment to neither getting exploited nor exploiting others for one’s gains, a heightened political awareness.

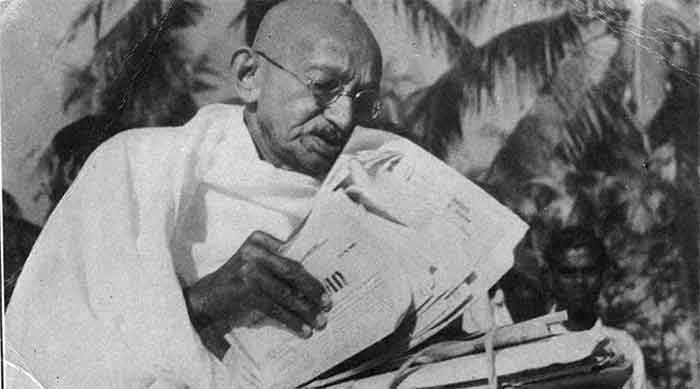

In this ongoing era of political repression, where a vast section of media has absolved itself of its duty and refuses to speak truth to power; where political opposition to the ruling dispensation gets branded as anti-national; where representing or speaking in favour of the marginalised is declared unlawful and bestows you national disrepute, where perpetrators of hate crimes and violence are garlanded and celebrated in broad daylight, adopting satyagraha as a guiding force to confront politics of division and silence can prove immensely helpful. It can invigorate political helplessness with a moral force that is purposeful even if the end seems further. And yes, the time for disobedience has arrived. Political power fears nothing more than defiance. If the citizenry organizes itself and launches civil disobedience demanding the cessation of hostilities by the government towards the ordinary people of this country, a new political possibility can appear. The figure of Gandhi, a man of frail appearance, who did not fear the might of the British Empire, who discarded not only western philosophical hegemony but also lifestyle, who extended his hand to the ‘others’ and fought for it too, who did not shy away from admitting his mistakes and asking for forgiveness, who organised masses not by creating divisions but finding common cause, who triumphed not though communal riots but popular mobilisation, is the need of the hour and the only force that can bring the plurality of this country together. Of course, the opponents of Gandhi, who celebrate violence, revenge and power would defame him and blame him for the miseries of this country. But while Gandhi’s’ opponents attack him vehemently, Gandhi’s ethical practice absolves him of many of the blames because there might have been errors, but there was also consistent accountability and transparency in his political practice.

Having said all of this, Gandhi is not above criticism. But one must acknowledge that despite his earlier limitations, he also evolved as a person, anticolonial campaigner, and philosopher over time. What makes his thought organic is its delicate balance between theory and practice. The contemporary political predicament makes it urgent that we return to his philosophical ideas to address conflicts in our society, but that will require sustained effort and patience.

Javed Iqbal Wani, Assistant Professor, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar University Delhi (AUD)