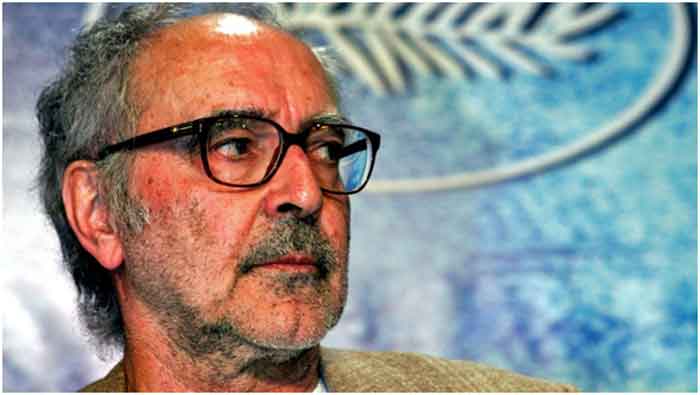

Jean Luc Goddard who left us at age of 91 on 13th September, ranks amongst the greatest film makers ever .Godard, was a filmmaker, critic, essayist, polemicist, philosopher, scientist, a preacher, educator, journalist, and artist rolled into one. The motion-picture medium was elevated to a new dimension by him, penetrating barriers untranscended in terms of creativity. Its hard to think for even a moment about what Godard meant to cinema, and not feel the huge vacuum it has left behind. The manner he knitted a plot or constructed scenes to convey a theme, without the slightest drop of sentimentalism, showed touches of genius.

Goddard was born into a wealthy Franco-Swiss family on December 3, 1930 in Paris’s plush Seventh Arrondissement. His father was a doctor, his mother the daughter of a Swiss man who founded Banque Paribas, then an illustrious investment bank. His interest in films sparkled in 1950, when he joined the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin. There he met Claude Chabrol and Francois Truffaut, who would also become influential members of the Nouvelle Vague. In 1960, Goddard made his first feature film, A Bout de Souffle or ‘Breathless’. The film, produced by Francois Truffaut and starring Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo, was the turning point in his career.

From the moment he sparkled onto the world cinema stage, Godard broke away from all conventional norms, entrenched rules and traditions and never merely sold his message at a platter. Throughout his career, he penetrated the skin of both radical politics and revolutionary aesthetics. Though he seldom travelled, his films consistently engulfed the whole world, delivering an incisive blow to imperialist/colonial legacies of the West and giving fraternal support with voices and images that revolted against it

For Godard, cinema was like an experimental laboratory of real life, which from a continuous state of flux led to a definite political shape. He freely tapped all forms of intellectual and aesthetic resources — from literature, philosophy, painting, news and archival footage. For him, cinema itself was the very clay and medium to construct films.

Goddard studied the American films and stars whose culture the Europeans aped and set about projecting a realistic style for the European audience.,as an alternative to the American style. He illustrated that scope existed to create something beyond mere factory films.

Goddard had the willingness to remain unpopular till he invented himself, which was a unique trait.He took innovation to heights rarely scaled in film making., like a man being re-born. Tremendous fluency and assurance was hallmark of his movies, even if people could not understand a word his films. His personality was in every frame. Often in his work he would contradict his own pre-planning. doing exactly the opposite to what he planned, but later it looked exactly like original format. Goddard captured the street scenes spontaneously. There was no separation between the film–fiction and documentary .Goddard innovated dynamic relationship between sound and image. Although Goddard exerted a major influence, at the level of impenetrability of being obscure, it would be wrong to hail Goddard as the single great saint of creative film. This is because many can use the tools or technology to come out on streets to emulate his style, rejecting concept of one personality in every frame, which is simply impractical today. Goddard was a chamelion of a kind, doing something completely fresh each time, or different styles based on what he had seen..Goddard gave the tools of cinema making to the future generation.

In a long and productive career, we see Godard initially as the incisive film critic of Cahiers du Cinema, then turning into the iconoclast filmmaker of the New Wave generation, as a Maoist in the Dziga Vertov group, and in the last decades, as one of the most self-reflexive chroniclers of cinema and his times. No other filmmaker in the world has reinvented himself aesthetically and relentlessly followed radical politics with passion. Hence, he was always considered a “filmmakers’ filmmaker”.

Goddard’s revolutionary and Marxist ideology was manifested by both his films and his public statements. He openly criticised the Vietnam War. Between 1968 and 1973, he and Jean-Pierre Gorin made a series of films with a strong Maoist message. The best-known of them is Tout Va Bien (Just Great, 1972), starring Yves Montand and Jane Fonda. But towards the end of 1970s, Godard was disillusioned with Maoist ideals. Goddard was deeply influenced by the ‘New Left’ brand of Maoism propounded by Louis Althusser that rejected concept of the party as a vanguard.and was firm opponent of Stalinism. Similar to Betrolt Brecht, he revolted against conventional Leninism.

Goddard liberated films from tradition by tapping two major sources. The first source was German playwright Bertolt Brecht and his theory of “epic theatre,” a method of political theatre that forces the audience to be at one with the ideas presented to them as opposed to passively absorbing them. For Brecht, the theatre should be an effective tool for getting viewers to see the world as it really is, as moulded by class struggle. The second source was Maoism. In La Chinoise with shades of artistic genius he fused Brechtian aesthetics and Maoist ideas. Brecht felt that the classical view of theatre as catharsis left the audience spellbound and indolent. He wanted the audience to adopt a critical attitude to exploitation, oppression, and class struggle.. In contrast to the dramatic techniques of the past, epic theatre reminded the viewer that the play is merely a manifestation of reality replacing reality itself, and thus the reality could be moulded like clay, making theatre a catalyst for revolutionary action.

Goddard’s relationship with Anna Karina was amongst the most captivating ever in film history. Reminiscing about working with Mr. Godard, she largely remembers freedom and fun.“We did not see ourselves as remaking cinema at the time, at least not in my view,” Myself and the other actors were not part of the industry; we weren’t inside the star system. We were running around, shooting in the streets, hiding behind trees to do our makeup. It was a very simple way of working.”

We appreciated that what we were doing was different through the way Jean-Luc directed us, physically,” she said on the phone. “In older Hollywood movies, a character will make an entrance, close a door, light a cigarette, sit down, have a drink. In Jean-Luc’s movies, you were doing everything at once, and sometimes you wouldn’t shut the door all the way. Sometimes your cigarette wouldn’t light on first try. You were always moving through the scene in an active way that was more like being than acting.”

Searge Dany stated “He is not just a great filmmaker… he excels at being the filmmaker who expects everything from cinema, including ‘that cinema should free him from cinema,,he is the last (to date) to have been the (coherent) witness and the (moral) conscience of what’s afoot in cinema. Godard was the conscience of cinema and its consciousness.”

Satyajit Ray stated “the first director in the history of the cinema to have totally dispensed with what is known as the plot line. Indeed, it would be right to say that Godard has devised a totally new genre for the cinema… It is a collage of story, tract, newsreel, reportage, quotations, allusions, commercial short, and straight TV interview — all related to a character or a set of characters firmly placed in a precise contemporary milieu. A cinema of the head and not of the heart, and therefore, a cinema of the minority”.

Progressive cinema needs to resurrect or re -innovate the work of Jean Goddard, in manner relevant today, with neo-fascism and neo-colonialism reaching unprecedented heights.I recommend readers to read “A fight on Two Fronts :On Jean Goodard s La Chinoise “ by Cosmonaut ,article by Justin Chang in Los Angeles Times an in e -flux journal by Irmgard Emmelhainz on ‘militant film making –Between Objective Engagement and Engaged Cinema.”I also recommend ‘Fragments o Early work’ on youtube in 2009.

Analysis of Movies of Jean Goddard

.In first feature “Breathless,” Audiences sprang out of a theatre in 1960 without understanding the essence of the film, but the movie’s dynamism dragged them right up along with it. Casting Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg into a lovers-on-the-run crime plot that had comic and tragic connotations.Goddard’s spontaneity of capturing the streets in that movie virtually redefined art of film making. A new perspective was given to transition of human relationship Over the first seven years of his career, Godard carved out an astonishing run of 15 features. From “Breathless” to “Week-end” (1967), which were an epitome of artistic invention and energy.

Many of his best-loved movies arose from this ’60s heyday, which pulled audiences , “Breathless” and “Band of Outsiders” (1964) were romantic gangster movies in much the same oblique way that “A Woman Is a Woman” (1961) was a musical or “Alphaville” (1965) was a piece of science fiction.

Godard’s political views were already in films such as Le petit soldat, about the Algerian War of Independence. But in his final film in the Nouvelle Vague genre, Week-End, he delivered a crippling blow against consumerism and bourgeois society. Then in the closing credits, instead of simply “Fin,” the screen lit up with “Le Fin du Cinéma,” or “The End of Cinema.”

Inspired by the May 68 protest movement that shook Paris and other European cities, Godard became increasingly politically outspoken. With his longtime friend Francois Truffaut, he led protests that shut down the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, to show solidarity with the students and workers.

To give aesthetic respect to his work it is imperative to examine the beauty in the consistent rupture and fragmentation, in states of confusion and sometimes crazy incoherence. To confront them theoretically is to grapple with subjects that range from the crassness of consumerism and mass culture, subjects he portrays with artistic fervour in “Masculin Féminin” (1965), to the flux in fortunes that ensnare the characters in “La Chinoise” (1967), his alternately satirical and sensitive portrait of young Maoist radicals. It means contending with his rejection of Steven Spielberg and Hollywood in “In Praise of Love” (2001), the masterly work that launched, a major artistic comeback, and also to appreciate his delusion over anti-Arab violence and conflict in both “Notre Musique” (2004) and ‘The Image Book (2018), his last released feature.

Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) narrates the story of French students in the 1960s who form a Maoist collective, live together, have political discussions, and eventually resort to revolutionary violence. The film lacks a symmetrical narrative structure, and the viewer is bombarded with slogans, images, and ideas on everything from popular culture to revolutionary politics.. Goddard’s objective was to extinguish the camouflage of bourgeois ideology that distorts how the world actual is.. He wanted film to turn into a medium of revolution.

Godard was strongly influenced by Brecht’s theories and used them in his films, to create the alienation effect. Godard employs the alienation to perfection in La Chinoise by making his characters directly address the audience and juxtaposing seemingly unrelated imagery side-by-side. Take the scene in which Guillaume, after arguing that revolutionaries need “sincerity and violence,” looks directly at the camera and says, “You’re getting a kick out of this. Like I’m joking for the film because of all the technicians here. But that’s not it. It’s not because of a camera. I’m sincere.”34 Guillaume continues to address the viewer by explaining what “socialist theater” is by telling a story about Chinese students protesting in Moscow. In this story, one student approached the Western reporters with his face covered in bandages, yelling, “Look what they did to me! Look what the dirty revisionists did!” When the students removed the bandage, the reporters eagerly awaited a cut-up face of which to take sensationalist photos. But when the bandages were removed and the student’s face was fine, the reporters became angry saying, “This Chinaman’s a fake! He’s a clown! What is this?!” But the reporters did not realize the significance of the demonstration. Guillaume explains: “They hadn’t understood. They didn’t realize it was theatre. Real theater. Reflection on reality. Like Brecht or Shakespeare.” Scene dissection is brilliantly executed, illustrating in a most subtle manner the circumstances and manner the youth relate and are swept to Marxist or Maoist ideology .

In ‘Masculin feminin’ Jean-Luc Godard introduces the world to “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola,” through a gang of restless youths engaged in hopeless love affairs with music, revolution, and one another. French New Wave icon Jean-Pierre Léaud stars as Paul, an idealistic would-be intellectual entangled in forging a relationship with the adorable pop star Madeleine (real-life yé-yé girl Chantal Goya). The love chemistry amidst an intense or volatile political scenario or climate is portrayed with high artistic zeal. Through their tempestuous affair, Godard illustrates a candid and wildly funny free-form examination of youth culture in pulsating 1960s Paris, mixing satire and tragedy in manner only Godard could.

. Movie lovers have long glorified the images of Anna Karina, Godard’s former wife and longtime muse, racing through the Louvre with her male friends in “Band of Outsiders,” and reflected on the innumerable meanings portrayed in a cup of coffee’s swirling surface in “Two or Three Things I Know About Her” (1967). They have swooned over the mad Technicolor collision of men and women, colours and styles in the magnificent “Pierrot le Fou” (1965) and the moody erotic languor of Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli in “Contempt” (1963), for many Godard’s supreme masterpiece and most emotional work, in which he deals with the end of his marriage and also that of the Hollywood cinema he grew up loving.

After the 1980’s he embarked into commercial films, bidding farewell to his Marxist ideals. Godard underwent a metamorphosis from a bespectacled, cigar-wielding new wave icon into something altogether more captivating for many to embrace. For his most committed partisans, he traversed broader horizons of cinematic meaning with movies like “First Name: Carmen” (1983), “Détective” (1985) and “Nouvelle Vague” (1990), on the road embarking with collaborative filmmaking projects and embracing the possibilities of digital video. For others, these decades were a period of regression, into ever more unexplored punishing realms of inscrutability.

Harsh Thakor is a freelance journalist who has researched on revolutionary art and films