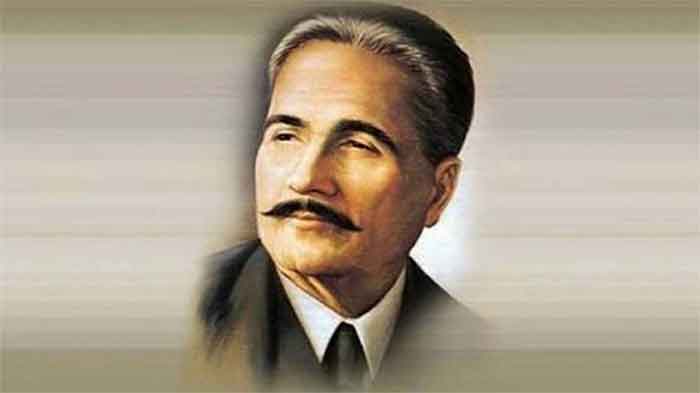

November 9, 2022, was the 145th birth anniversary of Allama Muhammad Iqbal – a globally renowned South Asian Muslim poet, and philosopher. The contemporary period of renewed cultural atavisms has reduced him to an ideologically zealous proponent of Pan-Islamism, leading to a crude anti-Westernism that rejects the universal values of freedom and equality to justify internal hierarchies within the Muslim community. In opposition to that exclusionary and hierarchical narrative of Islamic belongingness, we need to highlight the revolutionary and socialist strands of Iqbal’s thought, which used certain elements of Quranic teachings to articulate a new programme of socio-economic change.

Firstly, Iqbal said that the human being is a co-worker of God who carries within himself/herself the powerful capacity to implement God’s value of justice through human action in the present. We have the potential to become God’s khalifa or vicegerent on Earth. As embodiments of God’s divine will, we possess God-like powers – the only limit is God himself. On the earth, social and individual circumstances can work in such a way as to preempt the unfolding of our divine potential. In those situations, it is our duty to resist structures of subjugation since they disallow us from building a concrete relationship with God through the medium of worldly institutions. In this way, the strict acceptance of supposedly incontestable religious truths and practices is superseded by an emphasis on the earthy responsibility that individuals have to struggle in the concrete world for the establishment of a just social order. If we fail to use our divine powers of human creativity, we remain stuck in the state of mere biological existence, missing the emancipatory horizon of spiritual existence.

In other words, humans are both dust and God, nothing and everything. Here, significant comparisons can be made between Iqbal’s conception of Muslims and Karl Marx’s conception of the working class. In the latter, the material poverty of the proletariat is only the surface which hides the actual economic power they possess. Laborers are the source of surplus-value without which production can’t take place; if the workers stop showing up to work every day, the profits of the capitalist will dry up overnight. In a similar fashion, Iqbal exhorts the Muslims of the day to realize how the fact of colonial dominance was merely a historical accretion that hid the political power of Muslims’ God-given capacities. If the Muslim masses unitedly rejected any form of cooperation with the colonial authority, the imperialists would be forced to flee.

When we actively attempt to actualize our divine potential to the maximum degree, we come to recognize our khudi or self-respect. Iqbal was weary of his society because it was filled with various oppressions that prevented the people from using their creative capacities and thus cultivating self-respect. For this malady, Iqbal advanced the “courage of refusal,” the refusal to bow down to feudalism, capitalism, monarchy and imperialism, all of which killed the divine self-respect of human beings. This sentiment is evident in a trilogy of poems that Iqbal wrote about Lenin’s interaction with and impact upon God. In “Lenin in God’s Presence,” written soon after the Bolshevik revolution took place in Russia, Lenin defiantly asks God:

“You are Lord and You are Just but in your domain,

the hours of the laborer are crushingly difficult.

When will the regime of capital be sunk?

The world awaits the coming of Your judgment”

Lenin’s direct questioning of God underscores how humanity’s divine powers can be used to question each and every figure, including God. What matters is not the quietude of personal faith but the radical intensity of class struggle that materializes God’s norms of justice and equality in the world. In the second poem “Song of the Angels,” the angels respond to Lenin’s complaints by visiting earth. Addressing God, they say:

“Since the rich are trapped by luxury, the poor trapped by need,

the masses can’t rise from the streets, the elites can’t descend from heights.”

In the third poem “God’s Command to the Angels,” God recognizes the correctness of Lenin’s points and directs the angels to bring about deep-seated reforms in the world. Given the arousing tone of the entire poem, it is worth quoting it at length:

“Go bid the wretched of my earth to awake

The foundations of elite palaces should quake

Roil the blood of slaves with the pain of belief

Sparrows should challenge eagles, make no mistake

The moment of democracy is at hand

Signs of the old order I bid thee to break

Burn every ear of wheat of that field from which

The farmer is not permitted to partake

Distance between God and humans is futile

Remove the bishops from the church; they are fake

Build me a simple house with sand, for I hate

Those marble edifices. That’s a mistake.”

The stress on the undesirability of clerical institutions and the consequent foregrounding of a structurally transparent relationship with God brings me to the second theme of Iqbal’s work, namely the centrality of humans in the approach toward Islam. For him, the finality of Prophet Muhammad denoted the start of the period in which humans had to forsake subordination to any authority and instead begin looking toward the historical self as the primary source of life. “In Islam,” Iqbal explained, “prophecy reaches its perfection in discovering the need of its own abolition.” Like the dialectical constitution of the proletariat, whose development can occur only through its self-annihilation as an exploited class, the ultimate goal of prophecy could be realized only through its self-negation. This act of negation opens the way for the maturation of human independence which, in Iqbal’s words, “involves the keen perception that life cannot forever be kept in leading strings; that in order to achieve full self-consciousness man must finally be thrown back on his own resources”.

The finality of Prophet Muhammad and the centering of humanity means that one can’t rely on the abstract religious metaphysics of the ulama for concrete guidance in everyday life. This leads to taqlid i.e. the uncritical acceptance of a religious ruling from someone who is regarded as a higher religious authority. In antithesis to taqlid, ijtihad refers to the use of independent reasoning in the interpretation of Islamic sources. Whereas the former had been fabricated by the mullahs to secure their positions and perpetuate their monopoly over the sources of Islam, the latter functions as a tool for democratic reinterpretation, opposing the institutionalization of epistemological inequalities in the form of entrenched orthodoxies. Ijtihad insists that the human subject and its changing environment should be the criterion for the construction of all knowledge. In a quasi-existentialist fashion, Iqbal echoes the atheistic views of Jean Paul Sartre, for whom the death of God signifies the impossibility of deriving values from an intelligible heaven: “There can no longer be any good a priori, since there is no infinite and perfect consciousness to think it.” The abolition of prophecy and any kind of authoritarian priesthood leads to a condition of free choice, where the human individual is freedom, using his/her divine powers to bring about a socialist world. This, in essence, is the revolutionary spirit of Iqbal.

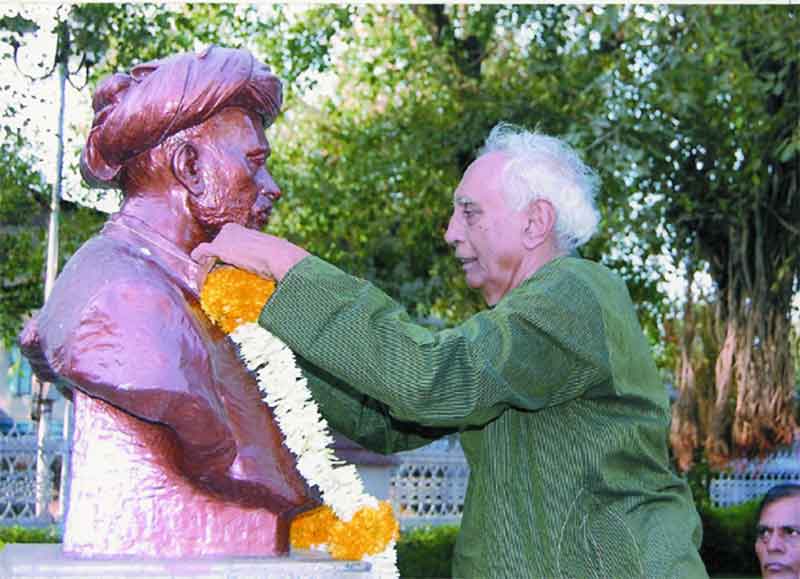

Yanis Iqbal is studying at Aligarh Muslim University. His theoretical pieces and articles on contemporary affairs have been published around the world, in countries such as the USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Netherlands, France, Greece, Italy, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Vietnam, Tajikistan, China, Turkey and several countries of Latin America and Africa.