The 3:2 majority judgement of the Supreme Court on 7 November 2022 giving the go-ahead for the 103rd Constitutional Amendment envisaging 10 per cent reservation for the Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) within the General Category raises an array of questions:

Is it in keeping with the notion of “JUSTICE, social, economic and political” as envisaged in the Constitution of India? If not, is it not a violation of the Basic Structure of the Indian Constitution? This question arises because according to the landmark judgement of the Supreme Court in the Kesavananda Bharati Case (1973), the objectives specified in the Preamble are part of the Basic Structure of the Constitution.

Is not reservation for the economically weaker among the privileged castes alone discriminatory and exclusionary towards the economically weaker among Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) and Other Backward Castes (OBCs)? This was also an apprehension raised by the minority judgements by Justice Ravindra Bhat and Chief Justice U U Lalit. Is it not a fact that there is an extensive presence of the economically weaker among these socially backward communities?

Does it not violate the stipulation of the nine-judge bench’s verdict in the apex court in the Indira Sawhney Case (1992) that “reservation should not exceed 50%, barring certain extraordinary situations”? The judgement had also specified that the backwardness mentioned by Article 16(4) is social backwardness. Will it not open a pandora’s box of a fresh wave of agitations for reservations by several otherwise well-off communities like Patidars in Gujarat, Marathas in Maharashtra and Jats in Haryana? The minority judgements on EWS quota had recognised the danger of breaching the existing 50 per cent limit on reservations.

How did the EWS quota come to be established in the first place without the backing of demographic and socio-economic evidence garnered through a Caste Census, the last of which was conducted in 1931? Evidently, electoral arithmetic of the ruling party at the Centre took precedence over real concerns of empowerment.

Provision for special measures for the amelioration of the conditions of the historically deprived and marginalised sections have not been specific only to India. In the United States, they are known as ‘Affirmative Action’; in Europe, as ‘Positive Discrimination’ and in India, as ‘Protective Discrimination’. The main measure of Protective Discrimination in India has been reservations granted in educational institutions and government employment. The ‘Social Protection Policies’ like pensions, scholarships, etc. recommended by Rajinder Sachar Committee Report (2006) for Muslims in India is yet another category of measures. The Sachar Committee was wise enough not to recommend reservations as a remedy for alleviating the backwardness of the Indian Muslims so that it would not lead to another round of communal frenzy against them.

It is a well-known fact that in India, mainstream media, academics, judiciary, and bureaucracy are largely controlled by the twice-born castes i.e., the General Category comprising of Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas. The Supreme Court judgement on EWS reservation itself may be considered as an expression of the prevalence of Brahminical hegemony in the judiciary of our country.

Perhaps, it is only in the realm of politics in general and electoral politics in particular that the OBCs i.e., the erstwhile Sudras in the traditional caste order, and the Scheduled Castes (self-named as ‘Dalits’), and Scheduled Tribes (self-named as ‘Adivasis’) enjoy a numerical advantage. It is no wonder therefore that most states in the mainland India have Chief Ministers from Backward Caste background. According to the Mandal Commission Report (1980), 52 per cent of the population in the country were OBCs. According to the 2011 Census, SCs and STs constituted 16.6 per cent and 8.6 per cent of the population, respectively; and the population of ‘non-Indic religious minorities’, namely, Muslims and Christians in the country were 14.2 per cent and 2.3 per cent, respectively. Together, these underprivileged sections of the population constitute a sprawling 93.7 per cent of the population, as per official statistics. In the language of Buddha and Kanshiram, they are the Bahujans, meaning the majority and in the language of Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, they are the Dalitbahujans of this country. However, the vast majority of them find themselves in the underclass of the 93 per cent of the workforce who constitute the informal sector workers in our country, the largest segment among them being self-employed. Exclusion continues to remain a stark reality in our country. Most of them do not find themselves in the discursive professions like media and academics that we mentioned above.

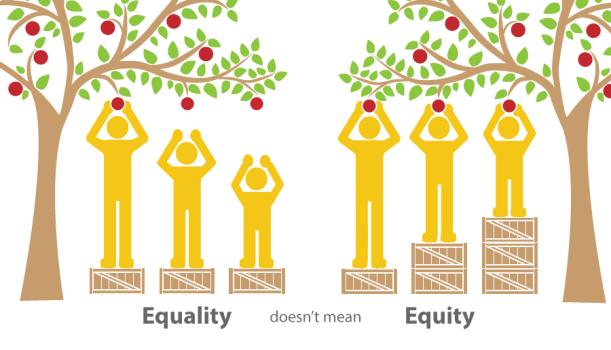

In such a context, can extending reservations to the already privileged 6.3 per cent of the population be considered a measure of Protective Discrimination? ‘Protective Discrimination’, as we understand it, is meant to ameliorate the continuing effects of the historical deprivation suffered by the marginalised communities. This is where we need to bring in the concept of ‘Preferential Treatment’, a term used by scholars like Marc Galanter. It could describe a condition where certain social section(s) which is/are already privileged by virtue of their social networks, socio-economic and educational conditions is/are privileged yet again. To draw on international experience, in Sri Lanka and Malaysia, the continuance of public employment policies in favour of ethnic Sinhalese and ethnic Malays, respectively even after they became socio-economically dominant, opened the way for their Preferential Treatment. Whereas Protective Discrimination extends rights to marginalised section(s), Preferential Treatment extends privileges to those already well-entrenched and privileged; in this case, to those ascriptively privileged by birth. Probably, this is the framework through which we could understand the policy of EWS reservation. Had the Supreme Court ruled against it, the struggle for the rights of the underprivileged could have been more orderly and peaceful which we may still hope for, through a saner verdict by the full bench of the Supreme Court.

Dr. Gilbert Sebastian (reachable at [email protected]) is an Assistant Professor at the Department of International Relations and Politics, Central University of Kerala. The views expressed are personal.