After February 2008 when Kosovo Albanian-dominated parliament proclaimed Kosovo’s independence (without organizing a referendum) with obvious US diplomatic support (unilateral recognition) with the explanation that the Kosovo case is unique in the world (i.e., it will be not repeated) one can ask the question: Is the problem of the southern Serbian province of Kosovo really unique and surely unrepeatable in some other parts of the world as US administration was trying to convince the rest of the international community?

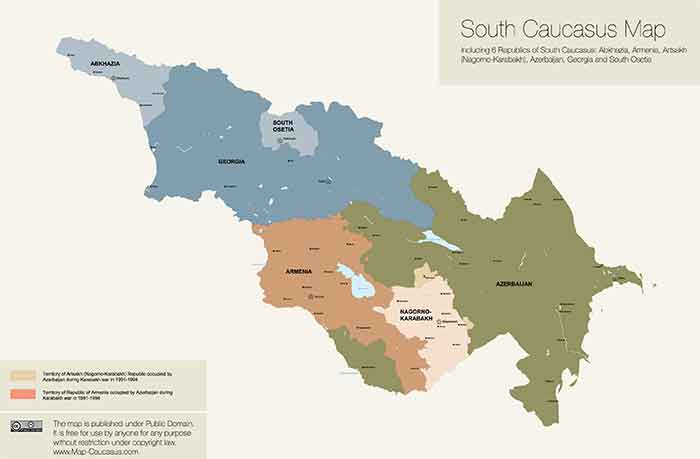

Consequences of recognition of Kosovo’s independence by one (smaller) part of the international community are already (and going to be in the future) visible primarily in the Caucasus because of the very similar problems and the situation in these two regions. In the Caucasus (where around 50 different ethnolinguistic groups are living together) self-proclaimed independence has already was done by Abkhazia and South Ossetia during their wars of 1991−1993 against the central authorities of Georgia but up to the mid-2008, both of these two separatist regions from Georgia were not internationally recognized by any state in the world. The region of Nagorno-Karabakh, which proclaimed its independence in 1991 from Azerbaijan with full military and political support from Armenia, was also not recognized before Kosovo’s independence. We must remember that separatist movements in the Caucasus in the 1990s occurred at the time when Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina proclaimed their independence from the rest of Yugoslavia (Montenegro and Serbia) and have been soon recognized as independent states and even became accepted members of the Council of Europe and the United Nations.[1]

However, only several months after the self-proclaimed independence of Kosovo on February 17th, 2008 a wave of recognition of three Caucasus separatist states started as a classic example of a domino effect policy in international relations. It must be noticed that the experts from the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressed even in 2007 their real fear that in the case of the US and the EU’s unilateral recognition of Kosovo independence the same unilateral diplomatic act could be implied by Russia (and other countries) by recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as a matter of diplomatic compensation and as result of domino effect in the international relations. It is also known and from official OSCE sources that the Russian delegates in this pan-European security organization have been constantly warning before 2008 the West that such a scenario is quite possible, but with one peculiarity: from 2007 they stopped to mention the possibility of Russian recognition of Nagorno-Karabakh’s self-proclaimed independence in 1991. It was most probably because Moscow did not want to spoil good relations with Azerbaijan (and Turkey) – a country with huge reserves of natural gas and oil.[2]

It can be said that the Albanian unilaterally proclaimed Kosovo independence in February 2008 is not at all a “unique” case in the world without direct consequences to similar separatist cases following the “domino effect” (Abkhazia, South Ossetia, South Sudan, East Timor[3], Crimea, Donbas…). That is the real reason why, for instance, the government of Cyprus is not supporting “Kosovo Albanian rights to self-determination” as the next “unique” case can be easily the northern (Turkish) part of Cyprus which is by the way already recognized by the Republic of Turkey (in 1981) and under de facto Ankara’s protection. Or even better example: the Spanish government does not want to recognize Kosovo’s independence for the very “Catalan” reason as a domino effect of separatism can be easily spilled over to the Iberian Peninsula.

It must be noticed that there are around 200 territorial-national separatist movements around the world for whom the case of Kosovo’s “precedent” is going to serve as the best moral and legal foundation for their independence. Subsequently, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh is recognized now by three non-UN member states according to Kosovo’s pattern: Transnistria, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia. Furthermore, in 2012 (four years after Kosovo’s independence proclamation), a member of Uruguay’s foreign relations committee stated that his country could recognize Nagorno-Karabakh’s independence. Further, the Parliament of New South Wales (Australia) called upon the Australian government to recognize Nagorno-Karabakh. Two other Transcaucasian separatist republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia became like Nagorno-Karabakh recognized after Kosovo’s independence proclamation in 2008 by several states and quasi-states: Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Nauru, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, Nagorno-Karabakh, Transnistria, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and Abkhazia and South Ossetia (each other).[4]

Kosovo’s independence proclamation in February 2008 became, in fact, not “precedent” as the US’s and the EU’s administrations declared: it became rather a boomerang example of a “domino effect” in international relations. The case of Crimea in 2014 was in this respect quite clear: the Crimean popular self-determination rights to separate the peninsula from Ukraine and to become part of Russia were at least formally founded on the same rights used by Kosovo’s Albanians (as a majority in the province) to proclaim the state independence from Serbia.

Dr. Vladislav B. Sotirovic Ex-University Professor, Research Fellow at Centre for Geostrategic Studies, Belgrade, Serbia www.geostrategy.rs Email: [email protected]

[1] On the Caucasian geopolitics, see [Chorbajian Levon, Patrick Donabedian, Claude Mutafian, The Caucasian Knot, Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Zed., 1994; Jorge Heine, “The Conflict in the Caucasus: Causing a New Cold War?”, India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs, vol. 65, no. 1, 2009, 55−66].

[2] On the issue of connection between geopolitics and energy, see [Klare Michael, Rising Powers, Shrinking Planet: The New Geopolitics of Energy, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2008].

[3] A referendum on the independence of East Timor was organized on August 30th, 1999, i.e. only 2.5 months after NATO aggression on the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (ended on June 10th, 1999 by the Kumanovo Agreement). After the Kosovo War, this province of Serbia became de facto separated from the motherland and independent in relation to Serbia. The formal independence of East Timor from Indonesia was achieved on May 20th, 2002.

[4] On quasi-states, see [Pål Kolstø, “The Sustainability and Future of Unrecognized Quasi-States”, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 43, no. 6, 2006, 723−740].