As J.M. Coetzee has written, taking ‘offence’ at something is usually a reaction of powerful and oppressive groups in the face of any challenge to their power or the possibility of losing it. Throughout the ages and across the world, the censorship of views, speech, depictions, expression, etc. has been rationalized in the name of ‘morality’, ‘decency’, ‘blasphemy’, and whatnot.

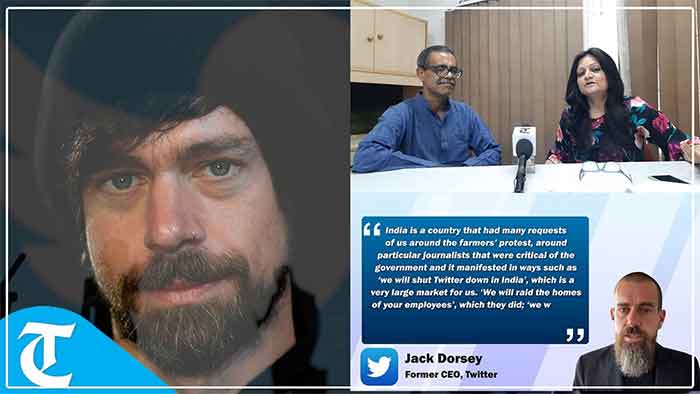

In most of these cases, the authorities entrusted with the task of maintaining morality by policing speech and expression represent and work for the dominant groups of that society, and India is no different. This can explain why a filmmaker can be harassed by online mobs and booked by police for depicting the Brahmanical (‘Hindu’) goddess Kali smoking a cigarette, or why Dalit woman activist Divya Bharathi faces intimidation and criminal charges for her documentary ‘Kakkoos’ on manual scavengers at the hands of Tamil Nadu police. Government critic Mohammad Zubair was picked up and placed in custody simply for sharing a tweet, and then reportedly asked why he only ‘fact checks Hindus’. This clearly shows an understanding of ‘fact checking’ as a discursive tool against the ‘other side’, which may explain the government empowering its press bureau to ‘fact check’ all news online. After some backlash, this will now be done by a ‘self-regulatory body’. Big win, huh?

What do these incidents, and others like them, have in common? A justification for government intervention in acts of expression and speech by citizens. And what is this justification? A perceived ‘insult’ or an act that is construed to be aimed at ‘hurting sentiments’. But what is so holy about ‘sentiments’ that they can’t ever be offended, mocked, or criticized? The opinions, commentary, narratives, and acts of expression emerging from society are bound to be as diverse as that society itself. ‘Sentiments’ encode sociocultural interests. Powerful groups will invariably have their ‘sentiments’ hurt when their dominance is challenged, or when a politically convenient moment arrives.

A case in point is Salman Khurshid’s book criticizing the ideology of Hindutva and likening it to Islamic terrorism: something that should be allowed unhindered in a democratic country, except that it got his property vandalized on the generally accepted pretext that he ‘hurt’ the sentiments of Hindus through the book. Who benefits from this? A purely political ideology that is excused from competing with other ideas on its own merits, getting a free pass to automatically becoming the default belief that everyone must conform to, i.e., Hindutva and Islamic terrorism are not comparable. I no longer need to be persuaded to believe this, since I am already expected to. If I don’t, I immediately become a member of an ‘other’ group. All the attacks and trolling that often come with not automatically agreeing to the state’s view are predicated on labels: ‘commie’, ‘Congressi’, ‘liberal/libtard’, ‘urban Naxal’, etc.

Remember the noise created about Gurmehar Kaur and her anti-war statements? She was specifically targeted by the regime’s media machine for somehow demoralizing the forces, again forcing a supposed connection between one person’s personal feelings and its imagined effects on an entire group. I wouldn’t even call her stance all that radical or profound. The intense pushback was an exercise in browbeating. It serves to remind the next person not to take up ‘sensitive’ issues, or else face the music.

The examples are endless. More recent ones are the fracas created over Rahul Gandhi’s ‘insult’ to the country abroad, mirroring an earlier faux ‘controversy’ around Vir Das’s “Two Indias” stand-up routine. Then there’s West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee being hauled up by a court for ‘disrespecting’ the national anthem, an illegal act in India. Suppose I want to protest the many ways in which the Indian state has failed and oppressed its own people: should I not be able to set my own lyrics to the tune of the national anthem and release it? Will this be considered ‘disrespect’? If yes, then by whom, and by what standards? What experiences will this judgement be based on? Accepting such an act as de-facto ‘disrespectful’ would erase the reality such a song wants to depict. It would cement the status of the national anthem as a sacred, unalterable hymn, ensconced in a Brahmanical aura of ‘purity’, safe from the ‘disrespect’ of those very citizens it is supposed to be sung for.

The underlying mechanics of prosecuting for ‘hurt sentiments’ also enable the regime of crushing speech in the name of ‘defamation’. Rahul Gandhi has recently been convicted for ‘defaming’ all Modis everywhere while his party colleague and MLA Jignesh Mevani was arrested and taken across the country from Gujarat to Assam for ‘defaming’ the prime minister.

Censorship is not just the enforced ‘disappearance’ of speech or ideas. It is part of an entire process of protecting power from threats. Expunging Rahul Gandhi’s speech from the Parliamentary record, making YouTube take down channels and videos for ‘spreading misinformation’, and scrubbing a BBC documentary on Modi from the Indian internet, shows us that Indian public discourse plays out against a backdrop of significant curbs and threats to free speech. “For speech concerning public affairs is more than self-expression; it is the essence of self-government,” says this well-known SCOTUS judgement. Are we a self-governing democratic republic if an artist can be arrested for his rap song that supposedly ‘defamed’ the present Maharashtra government?

While official statements will always be ready to justify these acts with boilerplate rationales, the actual point is to render invisible and stigmatize a position or narrative that is against the interests of the powers that be. This is done by presenting any act of dissent (intended or otherwise) as a threat to a collective interest posed by a small and insignificant number of outliers or troublemakers. It is here that ‘sentiments’ play their role, swelling up in irritation like our tonsils do as the first line of defence against the threat presented by a speech, a song, a film, and whatever else may be the target of censorship. The Indian government as a whole has ‘sentiments’ too, and is forever ready to hit back on newspaper articles or civil society reports from abroad, where its strong-arm methods of censorship cannot be directly applied.

Such is the regime of ‘hurt sentiments’, defamation, national image, and the lot. There are problematic, ugly, and distressing aspects of each society and its cultural history. The ‘pride’ that one group takes in its culture can very rightly be seen as hypocritical and oppressive by others. These are inherently divisive matters and the contradictions and extremes they create must be accepted within the rather exclusive ‘mainstream’ palatable to the Indian State today.

Arjun Banerjee is a writer and journalist.