The concept of ‘polycrisis’ is increasingly being used to designate the accumulation of compounding crises that human societies are facing, and that they are increasingly struggling to address and failing to solve. Yet this concept somehow misses the fact that there might be an inherent historical logic to the piling up and conjunction of these crises at this particular moment in time, as well as to the fact that whatever we are doing to address them appears to be failing.

(This is an excerpt, with minor adaptations, from a longer essay entitled “War and Peace in the Crisis of Complexity”, which you may find here)

Human societies the world over are confronted with a growing number and range of difficult and compounding problems and crises, which they are increasingly struggling to address and failing to solve, and which are slowly but surely eroding their ability to function effectively and undermining their capacity to coexist peacefully.

A term sometimes used to describe this situation is that of ‘polycrisis’, which has been debated in fringe academic and intellectual circles for some time but is now permeating into the mainstream, even if in a somewhat restrictive sense. This term captures the essence of an accumulation of crises that keep coming our way, which often seem to be unrelated at first yet pile onto each other and feed each other, to the point of overwhelming our capacity to cope and respond.

However, the concept of polycrisis somehow misses the fact that there might be an inherent historical logic to the accumulation and conjunction of these crises and problems at this particular moment in time, as well as to the fact that whatever we are doing to address them is not working. These crises and problems are not just piling up on each other by coincidence, out of bad luck or because of the sheer incompetence of the ruling elites, and a better characterisation of our situation is thus probably needed.

A few years ago, I suggested a possible concept and framework to characterise and understand the historical moment we are living through, which I called a “Crisis of Complexity”, and which I think provides a useful way to look at the likely causes, dynamics and consequences of our compounding and increasingly intractable problems. This concept is based on the work of American anthropologist and historian Joseph Tainter, and more particularly his seminal book on “The Collapse of Complex Societies” (Cambridge University Press, 1988).

Complexification and simplification

Investigating how and why complex societies or civilizations have been rising and falling in human history, Joseph Tainter uncovered a pattern that is very much relevant to our present situation, yet remains largely ignored or misunderstood.

Human societies, he showed, can historically be conceived as problem-solving organisations. They inevitably face a never-ending stream of social, economic and political problems, that they solve by developing new activities, new technologies, new institutions, new social roles, new forms of entertainment and recreation, by adding more specialists or bureaucratic levels to existing institutions, by adding organisational layers or increasing regulation, or by gathering and processing more or new types of information. These solutions, in turn, tend to create ever-greater socio-political, organisational and technical complexity. In general this growing complexity is not intentional, yet it is the inevitable result of societies’ successful attempts at solving the problems they are confronted with – and hence it constitutes a measure of their capacity to “progress”. In fact, the solutions that societies find to their problems and that they implement, as well as the actions and behaviors these solutions entail or generate, inexorably result in unintended and largely unpredictable consequences and end up increasing overall socio-political complexity, while also creating new and more complex problems. As societies’ complexity rises, the problems they have to deal with become more difficult to solve, requiring growing investment in problem-solving and hence in further socio-political complexity.

At some point, however, investment in socio-political complexity typically reaches a point of diminishing returns, meaning that the marginal beneficial returns (i.e. problems solved) of additional complexity start to decline, leading to a reduction of the capacity to solve the new problems that arise from this additional complexity and to deal with its consequences. These returns may even turn negative, at which point societies are not anymore capable of upholding the level of socio-political complexity they have reached. Typically, they then tend to experience a sudden and rapid loss of complexity, otherwise called “collapse”. According to Tainter, this dialectical movement of complexification and then simplification underpins human societies’ rise and collapse, and therefore constitutes the defining dynamic of human history.

If Tainter is correct, and he provides numerous examples of how this has played out throughout history, then it is likely that the industrial societies we are currently living in might also be entangled in this “Tainterian dynamic”. Ever since their emergence, modern industrial societies have continuously grown more complex, to the point of becoming, by far, the most complex human societies that ever existed. They keep getting more complex, year after year, in many different ways, yet they are poised to run at some point, like the societies that preceded them, into the diminishing returns of complexity.

The “energy-complexity spiral”

The main reason why industrial societies have been able to grow and complexify so much, according to Tainter, has been their capacity to access ever-growing supplies of affordable energy. The availability of abundant, inexpensive, high quality energy in the form of fossil fuels has indeed been instrumental in the development of industrial societies’ capacity to build increasing complexity into their economic, technical, political and social systems. Fossil fuels have provided human societies with unprecedented amounts of “surplus energy” (i.e., usable energy in excess of the energy consumed in the energy extraction/transformation/transport and delivery process), which have made it possible to increase socio-political complexity, which in turn has made it possible to solve certain societal problems, which in turn has then produced additional complexity, which in turn has required that the production of energy and other resources be further increased to meet demand and address the new problems that societies needed or wished to solve. This is what Tainter calls the “energy-complexity spiral” (Tainter and Patzek, 2011), by which socio-political complexity and energy availability feed each other and grow together, in a system of positive feedback.

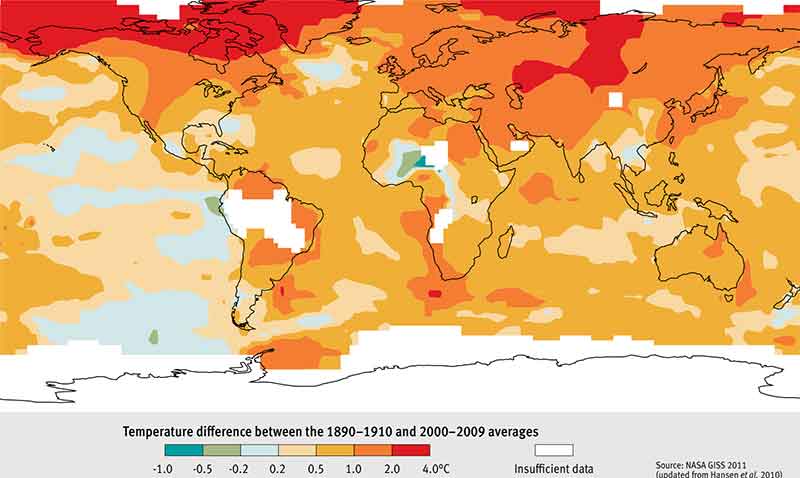

Humanity has been living in this energy-complexity spiral for over two centuries, and it has served it rather well during most of that time, powering an unprecedented growth of populations and of material living standards in many parts of the world. Yet the energy sources that have underpinned this growth, as well as the other natural resources they have made possible to use, are subject to depletion, which over time inevitably puts rising pressure and constraints on the quantity and quality of energy and resources that can be made available to societies and raises the cost and difficulty of doing so. In addition, the large-scale use of fossil energy also causes, directly and indirectly, massive environmental damage, including but not limited to climate change, which compounds over time and makes this use increasingly costly and risky. As a result, the ‘energy-complexity spiral’ based on fossil fuels, which underpins the very existence of industrial societies, is inevitably poised to stop propping us up the way it has been doing for the last 200+ years. It could even, potentially, turn from being an upward spiral into a downward one, bringing us down as the availability of surplus fossil energy shrinks.

Technical innovation that increases the productivity of energy and resource extraction and use may slow down this evolution, yet Tainter’s research shows that innovation in industrialised countries is also subject to diminishing returns and tends to become more expensive and less productive over time, meaning that it can only counter the effects of depletion for so long, and only partially.

For modern societies to continue benefiting from the rising surplus energy they need to solve their problems, a transition from fossil fuels to alternative, more qualitative and productive energy sources would be required. This is precisely what we are pinning our hopes on today, as we make plans for transitioning industrial societies, in just a few decades, to renewable energy sources (solar and wind power mainly) that will enable us to mitigate climate change while continuing to grow and to solve our other societal problems (i.e., complexify) as we have been doing for two centuries. We are making these plans because we have gotten so much used to living with plentiful and inexpensive energy that we now perceive access to surplus energy as a “normal” situation, almost a given, and believe that we have the capacity to decide where we get that surplus energy from.

The reality, however, is that our transition away from fossil energy is not happening – not yet at least. Fossil fuels still represent about 80% of the world’s final energy consumption, a share that has barely changed in the last decades. Modern renewables (solar and wind) have been growing fast for several years, yet so far they only exist as an extension of – or an add-on to – the fossil energy foundations of techno-industrial civilization. The reason why we are not transitioning away from fossil fuels is less related to a lack of political will or to the nefarious effects of vested interests, as we often hear, than to the insufficient energetic quality and productivity of renewables. On all the aspects that determine or influence energetic quality and productivity (energy density, power density, fungibility, storability, transportability, ready availability, convenience and versatility of use, convertibility, etc.), solar and wind energy are in fact significantly “inferior” to fossil fuels. Biophysical examination as well as empirical evidence so far shows that the capture of diffuse and intermittent energy flows and their conversion to electricity through man-made devices is, inherently, an imperfect substitute for the extraction and burning of concentrated energy locked up in coal, oil and gas, and hence that it might not be able to provide the same services and value to society or not on the same scale. Unfortunately, no amount of “innovation” seems to be likely to fundamentally change that.

Living at the end of a brief anomaly

In fact, the availability of surplus energy on the scale that we have been enjoying during the last couple of centuries and that we have come to consider as a given is anything but. It constitutes a unique occurrence in human history, and the conditions that we have been experiencing as a result of it are highly unusual, a historical anomaly, almost an aberration. There are growing signs that this aberration might be in the process of coming to a close, due to the inescapable and mounting impacts and consequences of fossil fuel depletion, and to the unavailability of alternatives that could really substitute them and keep our energy-complexity spiral running.

We might therefore have reached the point, identified by Joseph Tainter, where our societies’ standard way of solving the problems they face – i.e., investing in socio-political, organisational and technical complexity – is being undermined and rendered ineffective by the gradual breakdown of the energy-complexity spiral that has propped us for 200 years, and is thus yielding diminishing marginal returns. This would explain why we now seem to be getting more and more engulfed in a “polycrisis”, i.e., an accumulation of compounding problems and crises that we are consistently failing to address and solve, and even in many cases to just fully comprehend. As we are largely blind to the energetic underpinning of our industrial civilization and ignorant of the energy-complexity spiral, our reaction in the face of these problems that assail us is still to try to solve them by adding layer after layer of organisational and technical complexity, yet the cost of doing so keeps growing while the returns obtained (i.e., number of problems solved, or extent to which the problems are solved) irremediably goes down. And we remain largely clueless about why what we’re doing doesn’t seem to be working anymore and why major societal stressors keep accumulating and compounding across the board.

We are, in other words, in a ‘Crisis of Complexity’.

We might even be approaching the moment where the marginal returns on our investments in complexity turn negative, i.e., create more and bigger problems than what they solve. When that happens, our societies will become unable to uphold the level of complexity that they have reached, and we will get projected into yet another historical moment as we exit the ‘Crisis of Complexity’ and enter what American systems thinker Nate Hagens calls the “Great Simplification’. In principle, this shift should happen when the energy-complexity spiral identified by Joseph Tainter turns from an upward into a downward spiral, or at least that’s what it would signal. There is no way to precisely know when that occurs, though, and we will therefore only be able to become aware of this shift retrospectively and through a series of symptoms.

However, there are signs that we are now making, in a number of areas, problem-solving decisions (i.e., investments in complexity) that are likely to create more and bigger problems than what they are going to solve. This is the case, for instance, in the energy domain, as our growing investments in ‘clean’ energy technologies are increasing the overall cost and complexity of our energy systems without, so far, altering the trajectory of our greenhouse gases emissions and environmental degradation. This is also the case in the financial domain, as the exercise in perpetual bankruptcy concealment in which the world’s largest central banks have been engaged since the Great Financial Crisis is now quickly reaching its limits and increasingly failing to contain mounting financial stress. This is even more the case in the technological domain, where we are engaged in a wild rush forward towards the development of artificial general intelligence, which seems both unstoppable and uncontrollable. How far the rise of AI will go and what its consequences will be is unpredictable, but what we can be pretty sure of is that it will most probably generate more, bigger and more complex problems than whatever it will solve.

End-stage complexification leads to rising conflictuality

One of the key consequences of our ‘Crisis of Complexity’ is that by eroding the capacity of industrial societies to solve the problems they face it inevitably leads to a rise of conflictuality, both within those societies and between them.

Within societies, the growing inability of established political systems to solve the most important and pressing societal problems is resulting in a process of ‘sophisticated state failure’ and leading in some cases to a rise of civil unrest and political violence. This evolution is particularly noticeable in liberal democracies, as the stability and durability of democratic regimes precisely rests on their supposed ability to peacefully mediate and arbitrate between conflicting or opposing interests or values. As the ‘Crisis of Complexity’ advances and engulfs them, democracies are progressively losing this ability and falling into extreme polarization. In some cases, they then tend to degenerate into some form of oligarchy or drifting towards illiberalism, or even towards ‘soft authoritarianism’.

In Western democracies, rising polarization and conflictuality tend to build up around issues such as political governance (i.e., centralization vs. decentralization in decision-making), economic balance of power (i.e., localism vs. globalism in production and wealth distribution), and socio-cultural evolution (i.e., diversity and mandated inclusiveness vs. homogeneity and ontological cohesion). On these various aspects, democratic societies are increasingly struggling to uphold the level of complexity they have developed and are subject to strong forces that are pulling them down towards a lower complexity level (i.e. more localised economies, more nationalistic governance, more homogeneous societies, etc.).

Autocratic regimes, on the other hand, have no pretense to mediate and arbitrate between conflicting or opposing interests or values peacefully and through popular consent – they do so authoritatively and through coercion. Their growing inability to solve societal problems is therefore less visible than that of liberal democracies, yet it is no less consequential. What it translates into, typically, is a further hardening of authoritarianism, aimed at suppressing not just the public expression of dissent but its very emergence. Both Russia and China are examples of how this is playing out.

The ‘Crisis of Complexity’ is also causing conflictuality to rise between societies, as the progressive breakdown of the energy-complexity spiral undermines the capacity of nations across the world to find peaceful ways of mediating and arbitrating between their conflicting or opposing interests. Since the end of World War II, the world, and particularly the Western world, has enjoyed a period of rising stability and decreasing conflictuality, which started during the Cold War and persisted afterwards, with a marked decline in interstate and intrastate wars.

This “Long Peace”, as it is sometimes called, is typically thought to have resulted from economic progress, attributed to globalization and international trade, as well as from the spread of democracy and the deterrence effect of nuclear weapons. Yet it has probably resulted, more fundamentally, from the world’s ‘Great Acceleration’ along the energy-complexity spiral in the years that followed World War II. This acceleration was made possible by entering fully in the age of oil. The most powerful and versatile of fossil fuels, oil overtook coal as the world’s dominant energy source shortly after WWII, and provided humanity with a much bigger energy surplus than it had ever enjoyed before. By doing so it turbocharged population and economic growth and delivered unprecedented material prosperity and social stability to many parts of the world, while also making it easier for nations to settle their differences and coexist more or less peacefully despite their opposing views, values and interests. In other words, oil laid the foundation for a long and historically exceptional period of increasing stability and decreasing conflictuality, which seems paradoxical for a resource that is commonly perceived as the cause of most modern wars.

The advancing and inescapable depletion of the world’s oil reserves has already been changing this picture for some time, though. This depletion is the key factor undermining the energy-complexity spiral and is, fundamentally, what lies behind the endless accumulation of problems that our societies are increasingly unable to solve. A dwindling capacity to solve problems also means a dwindling capacity to find ways of coexisting peacefully, among the various groups that constitute modern societies, as well as among societies or nations themselves.

War in the ‘Crisis of Complexity’ – Cutting the Gordian Knots

As the energy-complexity spiral continues to break down, the conditions for peaceful coexistence between nations with opposing interests are vanishing, and international conflictuality inevitably rises, leading to war in some cases. War, it should be remembered, is “the continuation of politics by other means”, in the words Prussian general and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831), which means that it is a “problem-solving mechanism” that typically gets used when other problem-solving mechanisms fail or become unavailable. As the ‘Crisis of Complexity’ reduces the availability and effectiveness of other problem-solving-mechanisms, the likelihood of war being waged to solve lingering problems increases.

This rising international conflictuality inevitably focuses first and foremost on the main points of geopolitical friction, where the vital interests of key geopolitical players collide, and which constitute ‘gordian knots’ of the geopolitical chessboard, i.e. intractable problems that are or have become insoluble without the recourse to violence. Ukraine is and has long been such a geopolitical gordian knot, one of the world’s main ones actually, and one where armed conflict was already ongoing prior to Russia’s invasion in 2022. As the ‘Crisis of Complexity‘ eroded both the capacity of the opposing parties to live with this intractable problem and the availability and effectiveness of non-violent problem-solving mechanisms, the eruption of full-scale war in Ukraine was a logical development and was to be expected – one way or another, this gordian knot that cannot be untied has to be cut.

The War in Ukraine is therefore an unsurprising consequence of the ‘Crisis of Complexity’, and to some extent it was even a predictable one. It is also, however, an amplifier of this crisis, as it is deepening it and accelerating its march towards the stage where it triggers the onset of the next historical phase that awaits us, the “Great Simplification”.

Photo by Nicolas Hoizey on Unsplash

Paul Arbair is the pen name of a business and policy consultant with almost 20 years experience in management and policy consulting, mostly with the EU institutions.

Originally published by Paul Arbair blog