Ranajit Guha breathed his last on 28th April 2023 at Vienna Woods in Austria. Indisputably, he was the greatest historian of the past century, and his passing away is an intimate loss to the field of social sciences.

Guha was born on 23rd May 1922, in Siddhakati village of Bakarganj district, now in Bangladesh. He was born in a family of khas taluqdars, middle-sized landed proprietors whose lands came under the Zamindar-Praja system (Permanent Settlement). This experience impacted Guha’s intellectual and political inclinations towards Marxism. In his student days at Presidency College, Guha joined the Communist Party of India and became an active member of the party. In 1947, Guha went on to represent Communist Party at the World Federation of Democratic Youth in Paris. For the next six years, he travelled to various parts of the world, engaging with communist functionaries, and involved himself entirely in party work. He returned to India in 1953 to focus on academics. In the coming years, he had slowly withdrawn himself from the party after being disturbed by the USSR’s dealings with countries in the Eastern Europe, Stalinism, and internal politics in India’s Communist Party, culminating in his resignation from the party in 1956 when USSR invaded Hungary. Since then, Guha has involved himself entirely in lecturing and writing.

Guha has left behind monumental scholarship in English and Bengali on several themes concerning Indian society that continues to impact the disciplines of history, sociology, anthropology and linguistics. In 1963, Ranajit Guha published his first book, A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement. The purpose of this work, other than tracing the political economy of the working of the Permanent Settlement system and its impact on the agrarian economy, is to trace the intellectual origins of such a policy. This was a pathbreaking work when the generation of scholars working on pre- and post-independent India focused exclusively on Britain’s economic exploitation, destruction of the social fabric and influence on India’s political thoughts. Later, his reputation was sealed with the publication of the first volume of Subaltern Studies I: Writings on South Asian History and Society in 1982 (this series published twelve volumes till 2005). The main aim of the Subaltern Studies is to rectify and counter the elitism in Indian historiography, espoused in colonialist and bourgeois-nationalist historiography. The Colonialist school argued that the national movement was an outcome of a small group of Indian elites bidding for power by mobilizing against British rule. Bourgeois nationalists argued that the exploitative conditions of colonial rule angered the masses and nationalist elites brought together these masses to fight against colonial rule. Both these schools ignored the political agency of the masses to act independently. Subaltern Studies is aimed at studying the politics of the people, i.e., the way in which masses have contributed towards national movement and in the development of Indian nationalism on their own, independent of the elites. In his book Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (1983), a work that has long impacted history writing in India, Guha has set out to understand how peasants have developed consciousness and will to bring political change in their rebellions against the Britishers. This consciousness was later channeled into major national-wide movements led by Mahatma Gandhi. Such an exploration of the subaltern peasant consciousness formed the basis for Subaltern Studies. In the following years, the subaltern studies expanded to accommodate numerous postcolonial political concerns that include the questions of secularism, caste and Mandal politics, and gender.

Guha was also profoundly concerned about how scholars wrote about women’s role in the movements. The women were portrayed as mere instruments in the movement and passive beneficiaries of the movement’s outcomes. They were assigned no agency of their own in the struggles for self-emancipation and history writing became ignorant to “what the women were saying”. He emphasized re-writing the history that gives attention to women’s agency. In his essay The Small Voice of History, he stated that “the idea of equal rights would tend to go beyond legalism to demand nothing less than the self-determination of women as its content. Emancipation would be a process rather than an end and women its agency rather than its beneficiaries”. He envisioned a new historiography that is attentive towards women’s voices.

Ranajit Guha was a serious critique of the Indian state and democracy. In his essay Indian Democracy: Long Dead, Now Buried (1976), Guha lamented that Indian democracy “has long been dead, if it was ever alive at all. Most of the life was beaten out of it by Jawaharlal Nehru’s anti-communist crusades and the rest by his daughter during the decade of her draconic rule culminating in the ruthless campaign to destroy the Naxalites…. It signifies that so far as she is concerned no democracy is better than a dead democracy”. He ended his essay with a note of slim optimism: “The Corpse [of Indian Democracy], however, might revive, rise from its grave and walk our parched plains and dusty streets yet again. Perhaps, such optimism is true for our present times too.

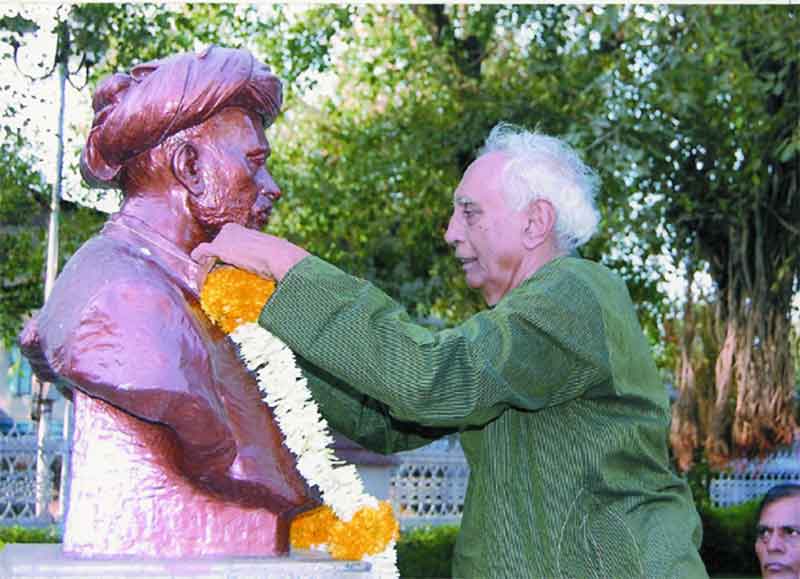

Guha was deeply impressed by Bengali language literature and intellectual traditions. He particularly admired Rabindranath Tagore for his genius and worldview. So, he started writing more in Bengali than English to engage with the Bengali language and literature more intimately. He published two volumes titled Kobir Nam o Sorbonam and Chhoy Ritur Gaan on Tagore, Daya: Rammohun Roy O Amader Adhunikata on Raja Rammohan Roy’s ideas of compassion, and several other articles in Bengali periodicals. In his Bengali writing, Guha also stressed the need to engage with Indian philosophy, which the present generation of Indians has overlooked. Guha himself engaged with the writings of philosophers like Bhartrihari, Abhinavagupta and Shankaracharya.

Many contemporary historians and political thinkers are trained, mentored, and worked alongside Ranajit Guha in the initial years of their academic careers. That includes Partha Chatterjee, Shahid Amin, Dipesh Chakraborty, Gyan Prakash, David Hardiman, Gayatri Spivak Chakraborty and David Arnold.

Guha has passed away, but his work will continue to have an ever-lasting impact on the social sciences. The project of Subaltern Studies is still unfinished.

Mucheli Rishvanth Reddy, MSc in International Social and Public Policy (Development) from London School of Economics and Political Science