Ahmedabad’s eastern peripheral areas include informal industrial clusters such as Vatva, Narol, Sarkhej, Ramol, Dani Limda, Aslali. These are well-known for a variety of industries that they house. The industries here include garments and textiles, pharmaceuticals, chemical processing, machine parts, wood processing, fabrication, plastic recycling, glass manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, transport, warehouses, small restaurants and hotels, garages, automobile servicing, electrical parts and gadgets, electronics, hardware, retail stores. A major sector amongst the different industries listed above, is textile and garments – forming almost 70 percent of the manufacturing industries in Narol. There are more than 2000 industrial units, and barring 35 large units, rest all are micro, small and medium enterprises. These 2000 units employ more than 2 lakh workers, most of whom are migrants from Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal

The small and medium sized units are usually dependent on receiving orders and contracts from bigger suppliers, who outsource or contract a specialized part of the production process to these units, such as: cutting, stitching, weaving, tailoring, printing, dyeing, washing, packaging, labeling, dispatching. There are also ‘supplier’ or ‘vendor’ factories, that the international garment brands such as H&M, Adidas, Marks and Spencer, GAP, Lewis, amongst others, regularly outsource the production. Some of the large textile and garment companies based in Narol, include the Chiripal group, Mahalakshmi textiles, Aarvee Denim, Jindal Processing, Komal Texfab, Mayank Processors, Krishna Processing, Gopi garments, Hemline Textiles etc. They produce range of products that include denims, pants, shirts, T-shirts, towels, bath robes, curtains, dresses, kids’ wear, sports goods, industrial wear, and other such accessories

The Narol industrial area is marked by two important elements – informality, and contractual/outsourcing jobs. Within this eco-system, the industries are known to flout industrial and labour laws, safety compliances, and regulations. For instance, a company needs to provide Provident Fund (PF) and Employees’ State Insurance (ESI), when there are more then 10 workers, in a unit, working on the floor. However, rarely do we see a worker getting PF and ESI, even though the unit might be having more than 10 workers working. A common practice is such that the large companies hire contractors on company’s pay-roll, who then hire workers to run a separate unit. The contract chain is so complicated that sometimes there might be eight to nine levels of contractors between the manager and the worker. At the same time, the labour department has made it easier for industrialists to flout the labour laws, as it provides the employers the option of self-registration, instead of audits and inspections by factory inspectors

An important aspect of the work in Narol, is the fact that large sections of both inter-state, and and intra-state migrant workers are hired by contractors in different trades related to garment manufacturing and processing, such as stitching, processing, printing, packaging, labelling, and boilers. Following table shows classification of workers involved in different trades in the garment sector of Narol:

| Section | Average Monthly pay (approx) | Male/female | Caste |

| Stitching | 9000 | Both | General, SC, ST |

| Processing (Dyeing, bleaching, washing) | 12000 | Mostly male | SC, ST, OBC, minorities |

| Printing, Packaging, Sampling, Checking | 10000 | Male, female | General, SC, ST, OBC, Minorities |

| Housekeeping and maintenance | 8500 | Mostly female | SC, ST, OBC |

| Boilers | 8500 | Both | Mostly ST |

| Home based work (stitching, embroidery, decorative materials) | 7000 | Female | General, SC, ST, OBC, minorities |

The large-sized companies, such as the ones listed above, easily employ more than 100 workers in different divisions. These companies have Trade Unions on paper, and for the purpose of maintaining their balance sheet and showing annual report to their shareholders, very few migrant workers actually working inside factories, whether on company’s pay-roll or on contract, actually know about Trade Unions or its office-bearers, and what functions do they serve. Only two trade unions – Karkhana Shramik Suraksha Sangh (KSSS) and Mill Mazdoor Panchayat, are involved in unionising and educating informal and migrant workers regarding labour rights, civic rights, and social security entitlements. Their experience in working and organising migrant labourers, shows three kinds of exclusions that migrant workers in Narol have to face: Economic, Social, Occupational

Economic Exclusion:

The economic exclusion is reflected through the pay system wherein the workers are provided payment below minimum wages, made to work overtime without overtime wages, no social security such as ESI, pension, PF, bonus, gratuity, no issuance of worker’s identity card, no paid leaves. In most cases, even the contract is not given to the worker at the time of his appointment. The workers receive cash from contractors for their labour, on daily basis. Most workers don’t have a bank account. The wages they earn are barely enough for them to meet daily expenses, leaving almost no savings at the end of the month.

At the same time, there are pay differentials between men and women, working in the same unit. Razia (name changed) (32), a migrant worker from Bihar living in Narol with her family, and working as a checker in a stitching unit says “We are paid per piece. There is no system to cross-check the payment we receive with the pieces we produce. Even though we produce more and calculate it on our own, the supervisor will find faults and say that a lot of pieces had to be rejected because they were not upto quality. We have been working for years and we know how to differentiate bad from good quality. Yet, our wages are deducted” This is just one example of gender based pay discrimination. A lot of women complain regarding how their pay for the whole day is deducted sometimes, even if they are a few minutes late to work.

Most workers in the garment factories are hired on contractual basis – contractual meaning they are only hired for a few months, and when the contractor or employing unit do not get a bigger order, the workers are fired. Raju (37) (name changed), a migrant worker from Rajasthan working in the washing unit, says “Earlier, 10 to 15 years back, the contract system was not so pervasive. It was only there in limited trades. But now it is the norm in this industry. Contract system has destroyed the morality of workers and employers both. Workers want wages at any cost, and are ready to do casual and daily wage jobs, whereas the employers have disregard for providing for workers’ well-being, their rights, their social security and safety. Today, if a worker meets with a workplace accident, the employer can easily say that he/she does not work for him and is not liable to pay for his/her treatment or any other costs”

Social Exclusion:

The social exclusion is reflected in terms of how the worker is excluded in the local governance and civic domains. Workers living on rental arrangement, find houses either in sub-par apartments or chawls, rented rooms, worksite housing, kacha or semi-pakka houses in slums, or in open spaces such as road pavements, under flyovers, open public plots, etc. A lot of workers also live within the factory premises, even though worksite housing is illegal. They live there since their wages are so less that they could not afford to spend on rent or commuting if they preferred living outside the factories. A lot of migrant workers do not possess domicile documents such as Aadhar, ration card, rent agreement, bank passbook, PAN card, amongst others, which makes it difficult for them to access government schemes such as PDS, LPG subsidy, health insurance, housing, and anganwadi or school admission for children.

The wages are barely enough for meeting the daily expenses. The union’s experience suggest that 80 percent of worker’s earnings are spent in rent and ration, barely leaving anything for health emergency, education, medical costs. A bachelor male migrant prefers to live in a dormitory or a rental room with other male bachelors and therefore the rent is less, but he also has to sent remittance to his family at source. The few public primary schools and anganwadis that are there in these areas, the medium of instruction is Gujarati, which is not the mother tongue of children of migrants. Therefore the children of migrants remain aloof from formal schooling, even if the family could afford. KSSS had appealed to AMC and the education department to include the Hindi medium language in public primary schools. Of the three public primary schools in the area, one school accepted the recommendation. After much deliberation, the AMC also started two anganwadis in Umang flats, one of the migrant localaities in Narol, where previously there was no schooling infrastructure.

Occupational Exploitation:

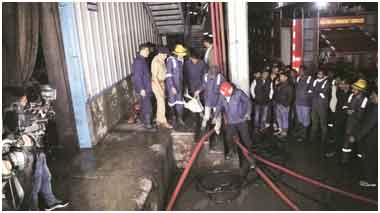

The occupational domain includes workplace safety, protection from health hazards, conducting medical tests for assessing workers’ fitness for work, training drills, machine safety (installation of censors), presence of on-site doctor or para-medical, on-site safety supervisor, provisioning of safety gears, etc. At the same time, there should be presence of a safety committee, Internal Complaints Committee for Prevention of Sexual Harassment (POSH), and labour redressal committee. However, these compliances don’t exist or only exist on paper. There is also lack of basic facilities at the sites, such as: lack of functional toilets, lack of ventilation, lack of restrooms, common spaces, creche for newly born children, lockers, access to safe drinking water, canteen, etc

Bhargav Oza is an Executive with Aajeevika Bureau, based in Ahmedabad. He has done his M.Phil at CEPT University, Ahmedabad; and is currently pursuing L.L.B. At Aajeevika Bureau, he works around labour collectivization, research and advocacy around Occupational Health and Safety for informal workers, and housing initiatives for migrant labourers