The Triumph Of Fantasy Over Science

By Rob Dietz

13 August, 2012

The Daly News

Part 1 The Rise of Fantasy as the Basis for Economic Policy

Two competing camps attract people from all over the world. One is Science Camp, and the other is Fantasy Camp.

At Science Camp, the counselors teach campers that we live on a single blue-green planet with finite resources. The curriculum at Science Camp focuses on figuring out how to conserve and share those resources. There’s a strong undercurrent of appreciation (maybe even reverence) for nature and humanity’s place in it — a desire to learn about and safeguard life on this planet.

At Fantasy Camp, the counselors educate campers to believe that humanity can circumvent natural limits. Campers are taught that our unstoppable ingenuity can overcome any resource shortages or manage any amount of waste generation. There’s a strong undercurrent of consumption — a desire to accumulate ever more power and stuff in an attempt to gain complete control over life (and even death).

This division of the world’s people into two camps is a bit crude. After all, some people can’t attend either camp, since they’re engaged in a struggle to get by on the meager resources available to them. Other people are so taken up by their jobs, ideology, or religion that they don’t pay attention to either camp. Still others may be in transit from one camp to another. For example, people learning the ins and outs of climate change, planetary overshoot, biodiversity loss, etc., might begin to disentangle themselves from Fantasy Camp and start leaning toward Science Camp.

Counselors and campers at Science Camp put a lot of stock in observations and facts. Facts like these:

>> When we extract and burn fossil fuels, carbon dioxide accumulates in the atmosphere. A higher concentration of carbon dioxide produces side effects (e.g., increasing temperatures and acidifying oceans) that threaten global climate stability.

>> When we convert forests, grasslands, and wetlands to farms, cities, and suburban sprawl, we decrease the amount of habitat available to non-human species, and we reduce the ecological richness of the landscape.

>> When we extract fish, trees, or other natural resources faster than Mother Nature can replace them, we collapse populations and sometimes cause long-term ecological damage.

Grappling with such facts can lead to clear-headed thinking about limits — recognition that we need to limit the burning of fossil fuels, limit the conversion of natural habitat, and limit the rate of resource extraction. Ecological economists are some of the most clear-thinking enrollees at Science Camp. They approach economic growth and ecological limits with practicality, seeking policies and institutions that enhance human well-being without overwhelming the capacity of planetary life-support systems.

In contrast, the people registered at Fantasy Camp, especially the neoclassical economists, tend to ignore, deny, or dispute facts that conflict with their pre-existing ideas about infinite economic growth. At the same time, they cling to tidbits of conventional wisdom that support their current worldview. Their refusal to incorporate facts into their thinking about how to operate the economy is especially dangerous because it feeds the consumptive frenzy that pushes ecosystems and societies to the brink.

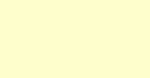

When you compare the foundational principles of ecological economics to those of mainstream/neoclassical economics (see table), it becomes ever clearer that one has a strong basis in reality. The principles of ecological economics stem from the laws of physics and ecology instead of “truthy” assumptions about human behavior and markets. The logic behind ecological economics suggests a different policy path than the theories behind neoclassical economics.

There’s one other big difference between Science Camp and Fantasy Camp. Science Camp draws many fewer supporters than Fantasy Camp. To make a positive economic transition, we need to orchestrate a reversal of this situation, and to do so requires us to address two questions:

1. Why do so many people pitch their tents in Fantasy Camp?

2. After decades of failing to attract people to Science Camp, what should we do?

Why People Favor Fantasy

As Bill Rees has noted, “If intelligence and logic were the principal determinants of economic policy, the primary goal would be to ensure that growth slows as we reach the optimal scale and that the economy not exceed this optimal size.” But given the struggle of ecological economics to gain ground on neoclassical economics, we can mostly eliminate “intelligence and logic” as driving forces that motivate people to decide which camp to enter. Indeed, three factors that have little to do with intelligence and logic are behind this.

1. The psychology of inclusion drives people to follow the in-vogue philosophy. Dan Kahan, a legal scholar at Yale University, defines the term “protective cognition” as a sort of automatic defense mechanism that people employ to dismiss scientifically sound evidence that poses a threat to their worldview. Like an immune system fighting off invading viruses, protective cognition works in people’s minds to repel invading facts that would require them to rethink their dearest beliefs. Kahan writes, “Because accepting such [facts] could drive a wedge between them and their peers, they have a strong emotional predisposition to reject it.” With so many people having internalized the concepts of unlimited economic growth and the triumph of technology over nature, protective cognition puts up a formidable obstacle to widespread adoption of ecological economics. It can take years of fact bombardment to begin chipping away at this obstacle.

2. Neoclassical economics has become entrenched in the culture. The way people approach daily living and interactions within the economy has become aligned with the neoclassical tenet of self interest (mostly by seeking high-paying jobs and adopting lifestyles of materialism). Neoclassical ideology permeates universities. With so many business and economics students, universities are churning out graduates who buy into the neoclassical approach. The degree of entrenchment came about because neoclassical prescriptions worked at a time when increasing material goods meant increasing well-being. As Herman Daly has pointed out, this was the case when the Earth was relatively empty of people and our stuff. We could extract resources and dump wastes without worrying about running out of supplies (of either inputs or waste absorption capacity). But that logic has become faulty, and even dangerous, as we have filled the planet with ourselves and our things.

3. They spin a real good story over at Fantasy Camp. The message of unending growth is enticing, as long as we disregard the Icarus-like consequences of being seduced by it. This message makes regular appearances in fantasy movies. For example, in The Matrix, Neo (the hero) says, “I’m going to show these people what you don’t want them to see. I’m going to show them… a world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries, a world where anything is possible.” Although this sort of message belongs in a movie theater, it seems to pop up even more often in the political theater. After Ronald Reagan cruised to Presidential victory over Jimmy Carter (whose message of conservation failed to resonate), he said, “There are no limits to growth and human progress when men and women are free to follow their dreams.” This quote, which makes it seem like Reagan employed Disney’s top talent to write his speeches, is literally set in stone in a Washington, DC monument. Reagan’s message is far more compelling than something like, “Individual freedom is a cornerstone of society, but freedom of choice may be constrained by social and environmental limits to growth. Men and women need to take such constraints into account when deciding which dreams to follow.”

These three factors won’t go away on their own. To increase the prominence of Science Camp, we have to take concerted action. Part 2 will explore how to enroll more people in Science Camp and supplant fantasy as the basis for economic policy.

Part 2 Restoring Science as the Basis for Economic Policy

Right now “economics” means “neoclassical economics,” especially in the halls of government and business boardrooms. At the same time, ecological economics remains an under-appreciated and under-utilized sub-discipline of economics. To reverse this situation, such that when people talk about economics, they’re talking about ecological economics, we need to address the three factors described in Part 1 of The Triumph of Fantasy over Science:

1. The psychology of inclusion drives people to follow the dominant economic philosophy (neoclassical), even if it comes straight out of Fantasy Camp.

2. Neoclassical economics has become entrenched in the culture.

3. The fanciful stories that support neoclassical theories are more emotionally compelling than the logic (straight out of Science Camp) that underlies ecological economics.

Overcoming these three factors requires three countermeasures.

Countermeasure 1. Frame the limits to growth and ecological economics in a way that prevents people from feeling threatened.

For decades, the denizens of Science Camp have been broadcasting messages about the shortcomings of neoclassical economics and the problems posed by its obsession with growth. To a lesser degree, they have also been promoting ecological economics (and its focus on well-being) as a positive alternative. But to bypass protective cognition — the defense mechanism that allows people to accept faulty premises — Science Campers need to frame their ideas differently.

Many people, when confronted with the possibility that the economic paradigm they’ve embraced may be harming society and causing significant environmental damage, react defensively. I know that I’ve been called all sorts of names (even the “C” word — communist) for presenting an alternative economic view. The key to disarming the defensiveness that comes along with protective cognition is to focus the conversation on needs that all people share (e.g., subsistence, security, and participation) and how an ecological economy can meet these needs without growth. Such framing can dampen denial and open minds.

For example, one time I was part of an “economic vitality” team tasked with providing ideas to a city council about how to achieve a prosperous local economy. The team included a sustainability guru, a business owner, a representative of the Chamber of Commerce, and a banker, among others. In one of our first meetings, I gave my standard spiel about the difference between a prosperous economy and a growing one. Since it was a small group seated around a table, I could see right away the misgivings some of my teammates had about my ideas. The banker must have set the world record for quantity of disapproving head shakes. We ended up butting heads for the next several meetings until I tried a different approach. I drafted a short document about our “areas of agreement,” which focused on the city’s needs. By steering the conversation toward things we all hoped to achieve in the city’s economy, such as available jobs, meaningful work, sufficient infrastructure, healthy ecosystems, and local production and consumption, we were able to have a constructive discussion and develop useful strategies for the city. Once the walls of protective cognition have been toppled, people can access their considerable capacity for logic when assessing policy options.

Countermeasure 2. Use student demand to supplant neoclassical economics in universities.

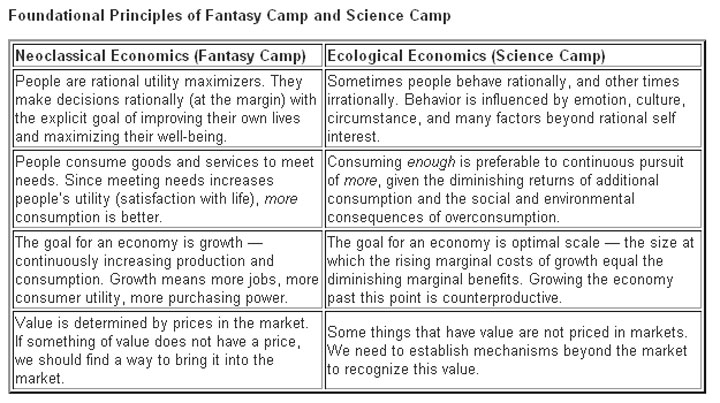

Since this countermeasure focuses on university economics, let’s use a couple of standard economic graphs. First let’s consider the production possibility frontier for teaching in economics departments (see graph). An economics department can offer only a certain amount of economics courses, defined by the production possibility frontier. If it is spending that “certain amount” on neoclassical economics, then it can teach very little ecological economics. The goal is to move along the curve from point A (where we currently reside) to point B where we want to be.

Since this countermeasure focuses on university economics, let’s use a couple of standard economic graphs. First let’s consider the production possibility frontier for teaching in economics departments (see graph). An economics department can offer only a certain amount of economics courses, defined by the production possibility frontier. If it is spending that “certain amount” on neoclassical economics, then it can teach very little ecological economics. The goal is to move along the curve from point A (where we currently reside) to point B where we want to be.

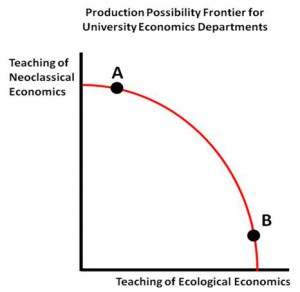

Now let’s use supply and demand to see how to move from A to B. The quantity (and price) of neoclassical economics offered by universities is determined by student demand and departmental supply (see graph). To lessen the quantity of neoclassical economics supplied, students need to lower their demand for it. This is a natural place to start, since neoclassical economics offers students very little in the way of long-term prospects for healthy and happy lives. Student uproar over the downsides of neoclassical economics is already percolating, and activists have begun organizing efforts to increase demand for ecological economics.

If students decrease their demand for neoclassical economics, then the quantity supplied will decrease.

For example, Adbusters started a campaign called Kick It Over that invites students around the world to join the fight to revamp Econ 101 curricula and challenge the myopic views of neoclassical professors. Another outstanding effort is Kate Raworth’s work with Oxfam on the “doughnut economy.” Raworth is trying to unseat neoclassical orthodoxy and replace it with an economic framework based on meeting society’s needs within nature’s limits. Besides offering a sound premise for structuring the economy, she suggests that students engage in a guerilla campaign to rewrite economics textbooks.

For example, Adbusters started a campaign called Kick It Over that invites students around the world to join the fight to revamp Econ 101 curricula and challenge the myopic views of neoclassical professors. Another outstanding effort is Kate Raworth’s work with Oxfam on the “doughnut economy.” Raworth is trying to unseat neoclassical orthodoxy and replace it with an economic framework based on meeting society’s needs within nature’s limits. Besides offering a sound premise for structuring the economy, she suggests that students engage in a guerilla campaign to rewrite economics textbooks.

As students decrease their demand for neoclassical economics, casting it into the dustbin of obsolescence, economics departments will move along their production possibility frontier to point B where their core will become ecological economics. At that point professors will focus their research on how to achieve sustainable and equitable well-being, and new generations of students will be grounded in the principles of Science Camp.

Countermeasure 3. Tell a better story.

Rob Hopkins, the founder of the Transition Towns movement has poked fun at the standard Science Camp story. He says, “Environmentalists have often been guilty of presenting people with a mental image of the world’s least desirable holiday destination — some seedy bed and breakfast… with nylon sheets, cold tea and soggy toast — and expecting them to get excited about the prospect of NOT going there. The logic and the psychology are all wrong.” We need to tell a more inspiring story about the transition to a steady-state economy.

That’s exactly what CASSE authors have been up to, and two new books will be available in early 2013. Enough Is Enough (by Dan O’Neill and me) and Supply Shock (by Brian Czech) will serve as a one-two punch to knock out the neoclassical obsession with growth. These two books can accompany the ecological economics textbook by Herman Daly and Joshua Farley to provide options for new economics courses along the path from point A to point B on the production possibility frontier. As more such books and resources come out of Science Camp, professors, politicians, and pundits will have fewer excuses for remaining in Fantasy Camp.

From reframing to organizing, from protesting to storytelling, there’s a lot of work to do to get past the collective mental block and start walking a sustainable economic path. For decades, we’ve shown ourselves to be incapable of accepting facts, unable to modify failing social institutions, and unwilling to adjust our lifestyles. But now is the time to overthrow the academic programs and economic institutions that got us into this mess in which we undervalue our most important assets. Now is the time to tell the story of ecological economics — the hopeful story of long-term prosperity on a healthy planet. Now is the time to demand the economy that we want and that the planet needs.

Rob Dietz is the executive director of Center for Advancement of the Steady State Economy (CASSE). Rob is a devoted advocate for revamping the economy to fit within biophysical limits. He lives with his wife and daughter in a cohousing community striving for development rather than growth.

Comments are moderated