This article is based on excerpts from a talk by Fr. Cedric Prakash at the second KP Sasi Webinar organised by Countercurrrents.org on “Religion and Spirituality in the Age of Fascism” held on 18 May 2025. The speech can be viewed from 12.46 to 31.57 minutes

What I know of K.P. Sasi can be summarized in three things. First, he had his heart where it mattered most—with the poor, with the marginalized, and with all those who were excluded and exploited in society.

Secondly, he used his capacity and talents as a filmmaker to highlight reality—whether it was the Narmada Dam, or the plight of Kandhamal, the victims there. His films gave voice to the voiceless, which is very important for us as we honour him and pay tribute.

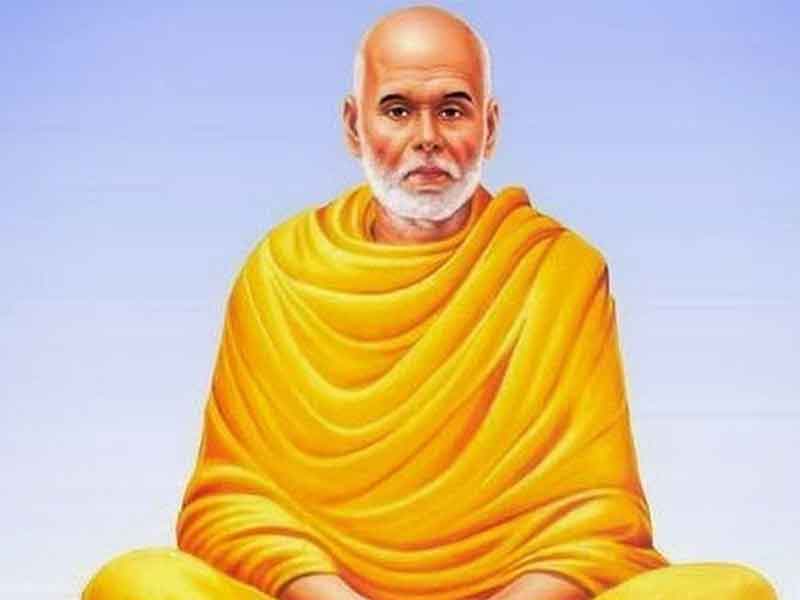

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, he was a deeply spiritual man. He may not have been religious in the conventional sense. He was certainly not a priest like me, but God will not ask you which religion you belong to, nor whether you were a priest of a particular faith, cult, or ideology. Perhaps the only question we will be asked after our life on Earth is whether we were spiritual persons.

Today’s topic, my dear friends, is about spirituality and religion in the age of fascism.

One of the people I quote often in my talks and seminars is Lawrence Britt, a social analyst and academic. In 2003, he published an article outlining 14 characteristics of fascism. He analyzed fascist regimes such as Hitler’s Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’s Spain, Suharto’s Indonesia, and Pinochet’s Chile. He concluded that these 14 characteristics are present in our country today—all 14 of them.

One of these characteristics is particularly relevant to today’s discussion: the intertwining of religion and government. Governments in fascist nations tend to use the majority religion as a tool to manipulate public opinion, even when the core tenets of that religion contradict the policies of the government.

I would like to focus specifically on India. There is no doubt that similar forms of fascism exist in several other countries, but I live in India, and recently I spoke to a group of around 350 young men and women from all over India gathered at Loyola Campus, Chennai, discussing what is happening in the country today.

To understand this, we need to look first at Article 25 of our Constitution. On 26th November 1949, the great men and women of the Constituent Assembly granted our country a Constitution that clearly guarantees freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, subject to certain limitations. This fundamental right shows that individuals have the freedom to choose and practice their religion without interference, provided it does not violate public order, morality, health, or other fundamental rights.

Recently, a High Court ruled that Article 25 of the Constitution does not give anyone the right to convert others. But this right is not about conversion—it is about whether I, as an independent citizen of India and an adult above the age of 18, have the freedom to choose the religion of my choice, or for that matter, stop believing in any god at all. Do I have the right to be an atheist? Do I have the right to be agnostic?

On March 26, 2003, a good friend of mine, Haren Pandya, who testified before the Citizens Tribunal, was killed in Ahmedabad. His body was found on that day. On the same day, the Gujarat government under the leadership of the current Prime Minister of India unanimously passed the Freedom of Religion Law, 2003. The opposition parties, including the communists, walked out and were not part of the decision-making process.

It took five years until 2008 for the government to frame the rules necessary to implement the law. After that, through our friend Girish Patel, we challenged the constitutional validity of the law in the Gujarat High Court. A group of citizens—including Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims—contested the law. According to the law, anyone who wants to change his or her religion needs permission from the civil authority.

I once called up the civil authority, a friend of mine at the time, and told him, “Until now, I believed in Jesus Christ as my God. But just before speaking to you, I’ve decided there is no God—I’m an atheist.” I asked him, “Who are you to tell me I cannot change my religion?” Don’t tell me atheism is an ideology. Atheism, like agnosticism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or any other belief system, is a form of faith.

When we challenged the law, the government could not respond, so they withdrew our petition. Even now, the issue remains in limbo because the government doesn’t know how to deal with it. These anti-conversion laws in various BJP-ruled states are pending before the Supreme Court, but the court has not yet constituted a full bench to hear the matter.

There are three points I want to make in the context of these laws:

First, who is the state to decide what religion I accept? Second, these laws talk about force and allurement in conversion. Allurement can be interpreted as any kind of enticement. If I say that by embracing my religion, you will gain a sense of freedom and equality, which are already enshrined in the preamble of the Indian Constitution, can that be termed as allurement? And third, what do we mean by the freedom to preach, practice, and propagate one’s religion?

It’s not just about Christianity or Islam. If a group in Ahmedabad goes about singing and chanting “Hare Rama, Hare Krishna,” do they have the legitimate right to do so? If a group of young men outside my institution want to distribute pamphlets of Jehovah’s Witnesses, do they have the right to do it? In Christianity, propagation of religion is not just articulation—it is witnessing. If someone accepts Christianity—or any other religion—because of weakness or vulnerability, is that considered allurement or force? These are matters of debate.

Fascist regimes across the world, as outlined by Laurence Britt, conveniently use this characteristic to manipulate and create a sense of majority alienation against minority communities. Here in India, the question arises: Does a person of one religion have the right to marry a person of another religion? Why should there be quotas or laws deciding this? If two people are in love and clearly express their mutual affection, why should anyone interfere? I know many excellent mixed marriages around the world where couples attend different places of worship, or none at all, yet they stand together in respect.

Now, coming to the second part of my sharing: One thing is rigid religiosity—the other is spirituality. Religiosity involves many rules, regulations, prescriptions, and prohibitions—man-made constructs. These are not made by God. God gives us faith, and God gives us spirituality.

Spirituality should embody a few key elements, as the late Pope Francis consistently emphasized. Some time ago, during a visit to Indonesia, Pope Francis said something very profound: “All roads lead to God.” Since Vatican II in the early 1960s, the Catholic Church and much of Christianity have maintained that all paths lead to God. It doesn’t matter who you are—if you embrace Christianity, that’s your choice. But how do we ensure that our daily interactions are infused with a spiritual experience, as K.P. Sasi so beautifully embodied both in his life and in his powerful films?

Before I conclude and give others a chance to speak, let me pose a final question: How do we, as men and women of goodwill, transcend divisions created by narrow interpretations of religion?

I presume that the 80-plus participants here at the webinar—and others who may join—are indeed men and women of goodwill. Many of you I know personally, and I recognize you as excellent human beings who have gone beyond the confines of religious dogma. So how do we create synergies?

When a Muslim is demonized simply for what he eats—when a goat becomes synonymous with Muslims and a cow with Hindus—we must realize that this is a deliberate tactic used by fascists to divide us in the name of religion.

My faith tells me that I am called to inclusiveness. I don’t build walls; I build bridges. I don’t discriminate against people. I was born and brought up in a building in Byculla, Bombay, where Hindus and Muslims lived together. We prayed together, played together, and even fought together. It didn’t matter if one went for Namaz or participated in Aarti, or if someone sang the Rosary at home—we all joined in. My school had students from every religion, including Parsis.

Before exams, all the boys and girls used to go and pray to St. Anthony because someone told us as children that praying to St. Anthony could help you pass even if you didn’t study—he’s the patron saint of hopeless cases. That was a time of syncretic religion, where synergies brought us together.

But today, in schools in Ahmedabad, when children play games like “chase the police,” the boys being beaten up are labeled as terrorists. Who creates this narrative? Who demonizes the other? Who weaponizes religion?

We still don’t know the full truth about Pilgrim. The government has refused to investigate thoroughly, and many people applaud this silence, saying innocent people are being targeted when they advocate against attacking Kashmiris or Muslims. Sedition cases are filed against professors and activists who raise questions.

In the name of K.P. Sasi—who brought us closer to spirituality, who helped deepen our faith, and who brought us together—not merely for this webinar, but for countless people—I appeal to each one of you, my dear sisters and brothers.

Let us embrace spirituality. Let us hold onto faith. Let us rise above the narrow confines of our own religions. Let us create synergies and realize that we are all sisters and brothers, as our Constitution says. It is fraternity that binds us.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Father Cedric Prakash is a Jesuit priest, social activist, and human rights advocate based in Ahmedabad, India. He is the founder-director of PRASHANT, a Jesuit Centre for Human Rights, Justice, and Peace, working extensively on issues related to communal harmony, religious freedom, and the rights of marginalized communities. Known for his outspoken critique of rising majoritarianism and fascism, he has been actively involved in defending constitutional values, promoting interfaith dialogue, and challenging anti-conversion laws and other state policies that threaten civil liberties.