In the opening of her 1953 short story “The Life You Save May Be Your Own”, the deplorable tramp Tom T. Shiftlet cannot keep his eyes off of “the square rusted back of an automobile.” He totally falls in love with a Ford that hasn’t run in fifteen years, which is sitting in a shed. His love-at-first-sight trembling is interrupted ever-so-briefly by a momentary glance at a sunset, but nature immediately takes a back seat to his passion.

He secures the vehicle by marrying Lucynell, the handicapped daughter of the woman who owns the automobile, Mrs. Crater. And before the story’s over, he will have abandoned his new wife at a southern roadside diner, driving off to Mobile, Alabama, as fast as he can in his true love — the stolen Ford. He’s what Hillary Clinton was imagining when she used the word “deplorables” on the 2016 campaign trail. She used the adjective as a noun, which is rarely done, but Shiflet is anything but unusual when it comes to American consumers, whether they were supporters of Clinton or Trump or Stein, or didn’t vote at all.

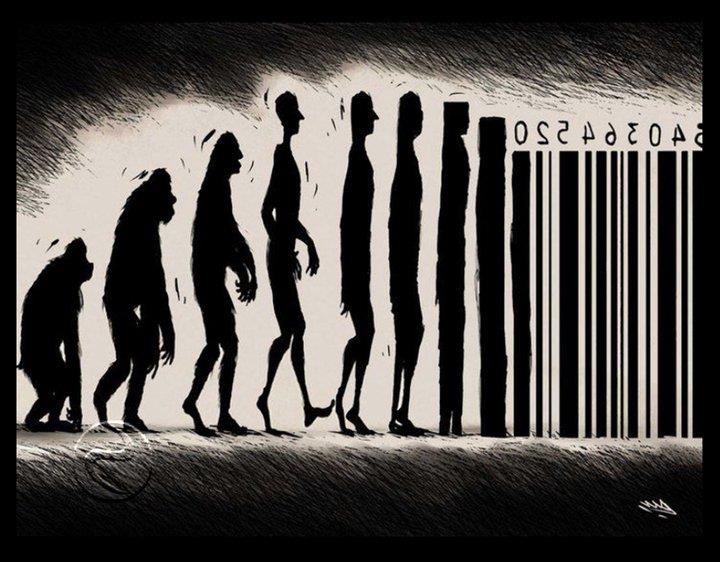

Falling in love with cars is common among the general public. And for many mid-century American authors and critics, O’Connor’s story was exactly about that. Yet in O’Connor’s hands the innocent, all-American scenario actually became a grotesque tale about desire deflected in terrifying, inhuman ways that reveal the unspoken truth about postwar America’s consumer society. O’Connor presents Shiftlet as a new kind of American who inhabits an alienating world in which the regime of mass production has collapsed the boundary between man and machine in ways both personal and physical.

O’Connor delineates this collapse with the inhuman image of Shiflet himself, a man she describes not only literally in love with an automobile but also figuratively as part automobile himself. Shiftlet is O’Connor’s model modern American, a conflicted figure driven to find meaning and satisfaction in things but also driven by a sense that the things he desires are essentially meaningless.

The story of Shiftlet’s choice of a Ford over his wife is a fable about the terrifying kind of person that the American worker has become: a machine-like consumer. And in some marginalized quarters a few token measures are being taken to reverse the horrid momentum that that dynamic represents.

For the reader to save her/his own life, though, will require deep self-reflection now. For it’s not just the physical products — easy targets of criticism — which must be reviewed, questioned, considered for elimination from our lives. We also consume exciting sports activity, aesthetically pleasing cinematic fare, and much more that’s not usually placed under the Umbrella of Consumption. [Can you compile a list of, say, ten examples? It should be easy.] They are the insidious, unacknowledged consumer evils in our lives.

The title of O’Connor’s short story, however, initially made me think about the slaves in Africa who produce the Silicon Valley products which have become the very foundation of general American culture. And for one’s personal salvation, it seems to me that in order to save one’s own spiritual life, it’s going to be necessary to save the lives of those who are enslaved worldwide, toiling away and wasting away so that our passion for products continues to be fed uninterrupted.

No one I know of is talking about our having to question our consumption of sports contests or cinematic fare. And — certainly — high tech gadgetry is off the table for consideration in the context I’m recommending. But I can tell you definitively that unless we get down collectively to transform out personal attitudes toward all that (and more that’s verboten), all the criticism of Trump’s Climate Change Denial, all the scholarly data compiled at the most prestigious institutions, and all the direct action in the world won’t amount to a hill of beans. Won’t be worth as much as a beat-up Ford from the fifties.

That said, if we do manage to focus primarily on saving others’ lives, not catering on automatic to our own habits, the life we save may be our own.

Rachel Olivia O’Connor is a freelance journalist. She can be reached at [email protected].