Education is instrumental in empowering girls and women, and eventually their entire families; therefore India is determined to educate all children, especially the girl child. By declaring education as a fundamental right, constitutional provisions were made to provide free and compulsory education to all children ages six to fourteen. Since the Right to Education (RTE) was enacted in 2010, gross enrolment has increased at a slower rate. In 2010, an estimated eighty-three of one hundred girls enrolled in primary schools (I–V classes) reached upper primary schools (VI–VIII classes), sixty-one reached secondary schools (IX–X classes), and only thirty-seven reached higher secondary levels (XI–XII classes).[1] Even after declaring education a fundamental right, numerous hurdles still prohibit a girl child from receiving essential education. Though girls’ participation in primary education has steadily increased over the last two decades, a substantial proportion of girls are still not in school. In particular, girls living in remote and rural areas and those belonging to “backward” castes and disadvantaged communities are excluded. Further, the quality of education in rural areas is a major concern. Girls continue to have too many obstacles to overcome and often have limited control over their own future. Lack of access to education is a primary reason that women do not have the opportunity to realize their potential.

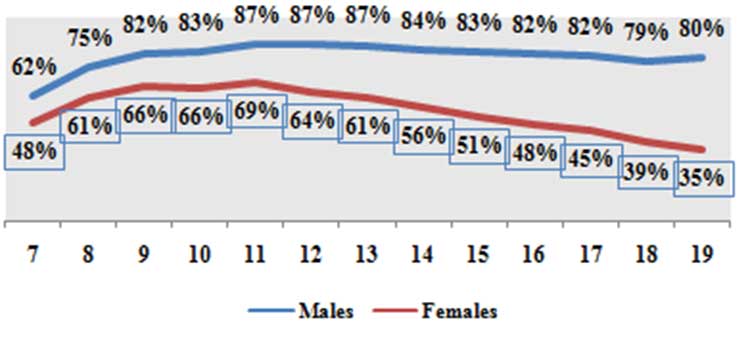

| Figure 1: Male and female literacy rates by age (Authors’ calculation through census data.) |

Muslim women are among the most disadvantaged, least literate, and most economically impoverished and politically marginalized sections of Indian society.[2] Mewat, in Haryana, is inhabited primarily by Meo-Muslims (79 percent per 2011 census) and women lag behind men in several development parameters. Per the 2011 census, about 48 percent of Muslims in Mewat are literate.[3] Among the literate population, 71 percent are male and only 29 percent are female. A similar staggering difference occurs between male and female literacy rates in different age groups. For example, 62 percent of males age seven are literate versus 48 percent of seven-year-old females. By age fourteen, males have a higher percentage increase of 22 percent, while the increase for females is only 8 percent (Figure 1). Access to educational institutions by girls is determined in large part by the social and cultural norms of the region and the position of women and girls in the society. Lack of access to schools is the major reason for the low female literacy rate.

Supply and demand factors both lead to low female literacy rates in the region. The demand side encompasses children, parents, and society in general, while the supply side consists of infrastructure and human and financial resources. The majority of the population sends their children to government schools because they are free. Parents in poor rural households are reluctant to send their children, especially girls, due to the poor quality of the education. Meo-Muslim families often prefer madrasa schools, which teach in Urdu, over the secular education imparted in government schools. The greater distances to middle and high schools is another factor for not sending girls for higher studies.

Why do girls drop out of school?

Focus group discussions held to understand the phenomena of pulling girls from the school system revealed that the parents of girl children consider women to be responsible for household chores that don’t require education. Parents don’t want to pay to send their girls to school. During the focus group discussion with girls, one girl described the typical trend, “Yahan toh maa baap sirf muft padhai ke chakkar me ladki ko aathvin tak school bhej dete hai.” (Parents send their daughters to school because of free education till eighth class.) To overcome these attitude barriers, parents need to understand that sending their daughters to school has value for girls and for their families.

On the supply side, the availability of high schools for both girls and boys is quite low. The district information system for education report 2014–15[4] showed a total of 979 schools in Mewat. Out of the 979 schools, 51 percent (500) are primary schools, 11 percent (109) have secondary schools, and 7 percent (69) have higher secondary classes. In rural areas the situation becomes even worse with only 38 higher secondary government schools for 450 villages.

The low teacher-pupil ratio and the poor infrastructure of many schools also lead to the dropout and lower literacy rates of girls. The DISE 2013–14 district report[5] shows that the average number of teachers per school (including government, private, madrasa, and unrecognized) is only six. Discussions with teachers in schools revealed that a shortage of teachers is a major issue in Mewat. Only one or two teachers are present in government middle schools. They do not want to come and work in rural areas due to the lack of infrastructure in the villages and the schools.

Boundary walls, school gates, electricity, rooms for classes and other purposes, playgrounds, etc., are dysfunctional or inadequate in the majority of schools. For girls, a major concern is the lack of or inadequate toilet and sanitation facilities at schools. Girls do not have access to safe, hygienic, and separate toilets at schools. Talking about menstruation is a taboo within the family and the community. Girls disclosed that after reaching puberty, their families do not want them to attend school, so they drop out. Similarly, having little or no access to drinking water affects absenteeism and a high dropout rate among girls and boys.

Requirements for improving girls’ education include building more high schools, improving sanitation facilities, and recruiting more teachers, especially females. Strengthening the linkages with employment opportunities will also help parents to see that spending money on education can provide benefits.

Many schemes, such as Kasturba Balika Vidyalaya, National Programme for Education of Girls at Elementary Level, Mahila Sangha, Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan, have been implemented by the government to reduce girls’ dropout rates. These schemes give special attention to weaker students. Likewise, women’s groups in villages are formed to follow up and supervise girls’ enrollment, attendance, and so on. Even with so many government programs and policies, India still lags behind in providing education to girl children. Challenges are not only in implementation but also in the level of commitment by people in general. Proper monitoring mechanisms are needed to ensure that girls have access to quality education. Better recruitment procedures and working conditions within the villages must be adopted to increase the number of good female teachers who might become role models for students.

Unfortunately many parents still tend to favor their sons more than their daughters. More education and awareness is needed to make parents understand that a girl is as much an important part of the society as is a boy. Both are the future of India. Both must be given equal opportunities for the development of our nation. In addition to quality education and infrastructures, the need to create awareness about the benefits of women’s education, education policies and programs, is essential to creating a healthier, wealthier, and more secure society.

Richa Saxena, Research Associate, Research, Monitoring and Evaluation http://www.smsfoundation.org

Notes

[1]Department of Secondary and Higher Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Govt. of India (Accessed from http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/SES-School_201011_0.pdf)

[2]Shinde, S. V., and A. John. (2012). Educational status of Muslim women in India. Review of Research, 1(6), 1–4.

[3]Census collects data on relative literacy rate. This article considers literacy rate as relative literacy rate.

[4]http://udise.in/Downloads/Publications/Documents/DistrictReport-2014-15-I.pdf (Accessed 3 March 2017.)

[5]http://udise.in/Downloads/Publications/Documents/DistrictReport-2014-15-I.pdf (Accessed 3 March 2017.)