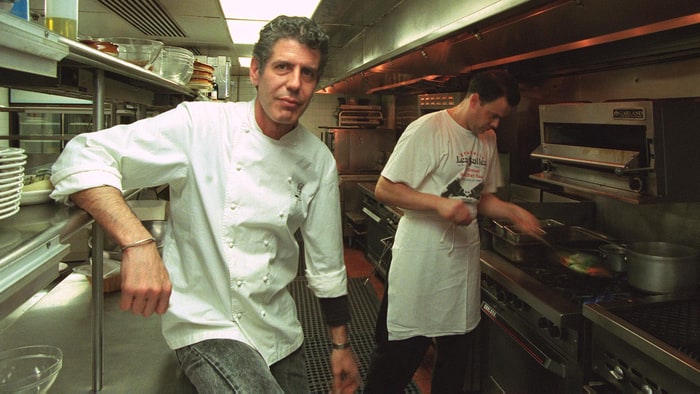

Without my glasses the trees outside the window are misconceived mosaics. No young breezes have come to play among them, nor has the west wind come to make them dance. It is only the residual droplets of water that create motion and a semblance of sound. The birds are quiet. It is a distinctly cold morning in Moscow. It is a good morning for old memories. And today, on the heels of Anthony Bourdain’s suicide, what I remember are days, long ago and far away, when, my legs tireless, my hands sure, my knife oh so quick, I stood before the flames in the heat of Hades itself, mixing together time, fire and ingredients in order to create satisfaction.

Unlike Anthony Bourdain, my career did not begin with a classy degree from one of the world’s most famous Chef schools, it began in the kitchens of dozens of restaurants as I was growing up. At the age of 14 I began working in small diners where I learned to flip hamburgers, fry potatoes, and make eggs five different ways. That led to a job at a very famous sea food restaurant the next summer where I honed my cutting skills as a salad chef. My big break came when the 2nd chef, wife of the first chef, had premature twins. Now, second chef at 15, I learned to make Lobster Thermidor, stuffed lobster, baked lobster, broiled lobster, and a variety of steaks for dinners, Shrimp Scampi for late morning bundles of hung over drunks who said it sobered them up, and the sauces: Bernaise, Hollindaise, Lemon, Teriaki, Tartar, Cocktail, the sauces for pastas. And all the while my knife became faster, more precise: I could peel and dice an onion in seconds. With the very tip of my broad knife moving like a slicer, I could take the skin off a melon in quarter of a minute.

It was hard work. It was dirty work. It was dangerous work: I slicked my fingers on machines, burn my hands frequently; grease splattered over my face, and the ovens burnt the sides of my legs. It was also hot work – the chef and I wore towels filled with ice cubes around our necks, constantly changing them out for new ones. We went outside periodically to vomit from the heat and gas. He often swayed and had to grab the side of the table to steady himself. When there was a minute, we sat on benches in the corner with our heads between our legs. But it was the early sixties, and I was a kid, a girl at that, and I brought home a good wage; a wage good enough for me to buy my first car.

When I moved to New York I worked in kitchens as well I worked in kitchens as a skilled chef. I learned how to do vegetarian cuisine. I studied macrobiotic and Japanese cooking; I became one of the very few vegan “chefs” at a time when everyone was looking for one. I got married had kids, got divorced, got married again, had another kid, got divorced again, and went to work as a “special chef for special diets.” I made money. I supported my three children practically alone. I went into business. I opened my own company. I did well – my own home, took good care of my kids, bought them cars when they turned 17. Such is the pride and self sufficiency that skilled labor gives one.

Of course, in the interim, and quite by accident, I got my education – undergraduate, graduate. Became a scholar and follower of Marx. But as I am always fond of saying, I never made any money to speak of with my mind – I made it all off the sweat of my back, the skill of my hands, and the speed of my knife.

The Psychopathology of Capitalism of course, revolves around the process of separationand individuation. But this reduction of all things to exclusionary ones has direct repercussions on labor – for it has reduced not just the worker, but also his labor to individual separate units. I will tell you something about how that occurred here, but if you really want to learn about how it happened you should read Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, the wonderful book by Harry Braverman first published in 1974 by Monthly Review Press.

My short story begins with Frederick Taylor. He can rightly be considered the first “management consultant.” What he did in a nut shell was to observe the movements of skill laborer as they worked. In doing so he noted their every movement and how that movement could be best performed. When he had done this he began to pay them very high wages to control those movements which he had broken down into their individual component parts. At that point, each part of the process could be done by a separate man, working in a kind of machine line fashion. And so it was that skilled labor, broken down into its component parts, and perhaps accompanied by machines, could be done by anyone. McDonalds could become a multinational corporation such that anywhere in the world, any unskilled individual could put together the same component parts to produce the same products.

Yet, even in the midst of the degradation of labor the power and dignity of skilled workers prevails. In different fields now in the fields of technology, computer science, advanced mechanics, and yes, in kitchens.

I will not lie to you. I miss being a chef. And I miss Anthony Bourdain, not just because he was a good chef or an interesting man, but because he was a spokesman for all those people who work in kitchens – immigrants, minorities and women. As he said: “We are clearly at a long overdue moment in history where everyone, good hearted or not, will HAVE to look at themselves, the part they played in the past, the things they’ve seen, ignored, accepted as normal, or simply missed — and consider what side of history they want to be on in the future.” – Medium

Mary Metzger is a 72 year old retired teacher who has lived in Moscow for the past ten years. She studied Women’s Studies under Barbara Eherenreich and Deidre English at S.U.N.Y. Old Westerbury. She did her graduate work at New York University under Bertell Ollman where she studied Marx, Hegel and the Dialectic. She went on to teach at Kean University, Rutgers University, N.Y.U., and most recenly, at The Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology where she taught the Philosophy of Science. Her particular area of interest is the dialectic of nature, and she is currently working on a history of the dialectic. She is the mother of three, the gradmother of five, and the great grandmother of 2.