Introduction

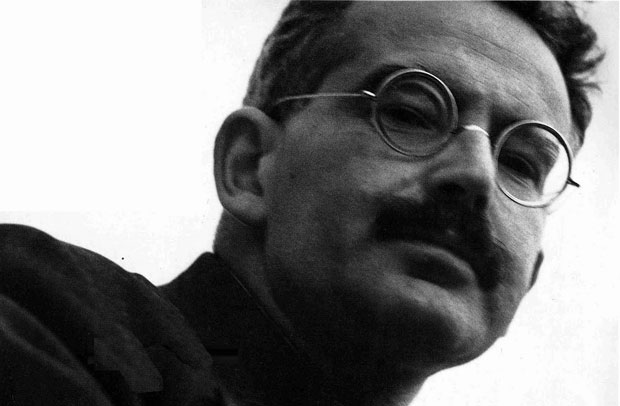

The German-Jewish critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) is at the present commonly regarded as one of the most important witnesses to European modernity. Walter Benjamin was known as great thinker, critic, social commentator, and theorist has become even more apparent in the English speaking world. The period from the 1910s to the late 1930s witnessed historical and intellectual changes whose effects are in many ways still being played out in the postmodern. For Benjamin, in particular, this meant not only the political effects of nineteenth-century capitalism and the social transformations they fostered but also an intellectual journey that begins under the influence of neo-Kantianism and progresses through German idealism, Freud, Surrealism, the kabbalah, Marx, and Brecht. The different stages of this career mark the extent to which Benjamin also offers an index to some of the dominant influences on the social, political, and intellectual history of the twentieth century as it forged its modernity. His tendency is to read how the work of others grappled with issues that were essential to his own time and intellectual formation. Walter Benjamin’s enigmatic legacy has generated a vast and growing body of commentary and interpretation. His contributions to metaphysics, theology, cultural history and literary and art criticism are at once forbiddingly abstract and sensitive to the most inconspicuous, concrete detail.

The response of the work of the Weimar philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) has vindicated his own insight into the ways in which the past is continually transformed through its interpretation by the present. The body of his writings bears the scars of the various disputed phases of its postwar reception, whether Marxist, theological, cultural critical or philosophical.

Writing from Paris to his closest friend, the Judaic scholar Gershom Scholem, on 20th January 1930, the German-Jewish philosopher, literary and cultural theorist Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) makes his intellectual ambition plain: The goal I had set for myself has not yet been totally realized, but I am finally getting close. The goal is that I be considered the foremost critic of German literature. The problem is that literary criticism is no longer considered a serious genre in Germany and has not been for more than fifty years. If you want to carve out a reputation in the area of criticism, this ultimately means that you must recreate criticism as a genre. (COR, p. 359) This is a particularly ironic and peculiarly appropriate statement. It is ironic because of Benjamin’s own precarious, marginal situation at the time of writing: the enforced withdrawal of his Habilitationsschrift1 a few years earlier had ended any hope of an academic career, and he was now limited to eking out an indigent living as a freelance writer, reviewer and translator, and even as the author and narrator of radio broadcasts for children. Indeed, Benjamin was to return to Paris only a couple of years later in the even more impoverished guise of a refugee fleeing Nazi tyranny. If Benjamin was to become the ‘foremost critic of German literature’, it was to be an expertise in exile.

Biographical outline

In contrast to the impecunious and imperilled condition of his later life, Benjamin’s childhood was a time of material comfort and tedious tranquillity. Born on 15th July 1892, the son of an auctioneer and eldest of three children, Walter Benedix Schonflies Benjamin grew up in the desirable West End of Berlin in an affluent, assimilated German-Jewish family. As has been commonly observed, his semi-autobiographical reflections on his formative years, ‘A Berlin Childhood around 1900’ and ‘Berlin Chronicle’ (both written in 1932), are more treatises on the promises and prohibitions attending a middle-class, urban childhood in general than an intimate account of Benjamin’s boyhood. He recalls a solitary, sickly childhood cloistered in the insufferably ‘cosy’, cluttered bourgeois interior of the time, the dull and dutiful round of visits to ageing, gossiping relations, and the petty strictures of school life. His reminiscences speak eloquently and poetically of a child whose main consolations for this dry existence consisted in the daydreams stimulated by reading, in the visits to the enchanting Tiergarten and Berlin zoo, in the annual hunt for Easter eggs, the occasional illicit nocturnal pilfering of confectionery, and, on one memorable occasion, an unintended, unsanctioned foray into a seductive, seedy district of the city. In the belief that he would benefit from the country air, Benjamin was sent away from Berlin to spend two years (1905-6) at a relatively progressive boarding school at Haubinda in Thuringia. There he met and studied under Gustav Wyneken (1875-1964), a key advocate of educational reform and a luminary of the radical wing of the Youth Movement (Jugendbewegung). Originally formed in 1901 as a boys’ hiking organization, the Youth Movement in Imperial Germany expanded and diversified to cover a wide political and social spectrum, from proto-Fascist, anti-Semitic elements such as the Wandervogel with their Volkish ideologies, eulogizing of German nature, sense of martial brotherhood, and privileging of leadership, to the Jewish section of the movement, the Blau-Weiss. The radical wing of the Youth Movement to which Benjamin was attracted advocated a complete break with the traditional school system to ensure the free development of youth unencumbered by the dogmas and disciplines of conventional pedagogy. The renewal of German culture and intellectual life could be achieved only through the liberation of youthful creativity and energy. Under the influence of Wyneken, Benjamin became intensely preoccupied with the cultural and educational condition of youth, though not in any practical or instrumental sense. Benjamin’s vision of the mission of students, unsullied by material or political considerations, was couched in the rarefied and abstract terms of the idealistic renaissance of Geist (spirit), the solitary, individual life of the mind. Although Benjamin returned to complete his school studies in Berlin and then enrolled to study philosophy at Freiburg University in 1912, he remained in regular contact with Wyneken. The year 1913 saw the publication of a number of poetic and idealistic polemics in Wyneken’s journal Der Anfang (The Beginning) as Benjamin returned to Berlin once more to pursue his university studies. Back in his native city, Benjamin was elected to the committee and then to the chair of the ‘Free Students’ (Freie Studentenschaft), an association instigated to combat the various conservative and martial university fraternities and clubs. This official position notwithstanding, Benjamin’s days of involvement with the idealism of the Youth Movement and the naive student politics of the ‘spirit’ were numbered. It was August 1914 was to make over everything. The outbreak of the Great War split the Youth Movement into its numerous factions. Some militants relished the outpourings of patriotic sentiment and the opportunity for imperial adventure and military glory. Some viewed the conflict as the necessary defence and revitalization of German Kultur, in opposition to the decadent foreign especially French values of Zivilisation. Some saw the war from the very outset as an appalling, futile sacrifice of a betrayed generation, and there were others who changed their minds. In 1913 Wyneken had criticized the warmongering and national fervour of the time, youth must resist the simplistic appeal; Of sabre-rattling sloganeering. In November 1914, however, his speech on ‘War and Youth’ in Munich was a rallying call to youth to defend the besieged and beleaguered ‘fatherland’. Expecting to be called up anyway, Benjamin initially, and without any enthusiasm, volunteered to join the cavalry, but, fortunately for him, was deemed unfit for military service. Subsequently, on 8 August 1914, two of Benjamin’s closest friends, Fritz Heinle and Rika Seligson, committed suicide as a despairing protest against the hostilities. Deeply moved by these deaths and feeling utterly betrayed by his mentor, Benjamin broke completely with Wyneken in March 1915. Three months later Benjamin met an 18-year-old student of rnathematics, Gershom Scholem, an acquaintance who would prove a lifelong friend and profoundly influence Benjamin’s work in the direction of Judaic thought, mysticism and the Kabbalah. Benjamin’s concern with the critical, spiritually redemptive task of youth gave way to a preoccupation with redirecting philosophical enquiry away from the impoverished Enlightenment conception of experience, cognition and knowledge, towards an understanding of the linguistic grounding of truth in Revelation. In his enigmatic fragments from 1916-17, Benjamin identifies the task of philosophy, to call things by their proper names, as the recovery of the perfect language with which Adam named Creation at God’s behest. Benjamin thus sought a new avenue for his concern with the purity of a language and an intellectual realm uncontaminated by immediate interests and instrumentalism. Both those who advocated Jewish assimilation within the German state, like Hermann Cohen, and those who later came to advocate Jewish political mobilization and emigration, like Martin Buber, were tainted by their initial enthusiasm for the war. Indeed, the politics of Jewish militancy and Zionism were far too pragmatic and partisan to appeal to Benjamin at this time, and his political thinking eventually took a rather different direction. He never learned Hebrew, though he promised Scholem on numerous occasions that he would do so; and he never even visited Palestine when Scholem emigrated there in 1923, let alone emigrate himself. Benjamin had been profoundly disappointed by his studies at the University of Freiburg, especially the lectures of the pre-eminent neo-Kantian philosopher Heinrich Rickert, which he found particularly boring. Subsequently, he showed considerably more enthusiasm for the classes and ideas of the sociologist Georg Simmel at the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. But in the aftermath of the break with Wyneken, Benjamin was keen to leave the imperial capital. In the autumn of 1915 he moved to Munich, ironically the city where Wyneken had recently delivered his fateful ‘War and Youth’ address. Benjamin managed to avoid subsequent call-ups by feigning sciatica, and in 1917 relocated to neutral Switzerland and Berne University with Dora Kellner, whom he had married in April 1917. Benjamin spent the remaining war years in self-imposed Swiss exile, and completed his doctorate on ‘The Concept of Art Criticism in German Romanticism’ in 1919, a study in which he sought to develop a notion of immanent criticism as the unfolding of the inherent tendencies of a work of art, its ‘truth content’, through critical reflection. Back in Germany, he subsequently provided an exemplary instance of such an approach in an extended essay on Goethe’s peculiar novel Elective Affinities. Eschewing conventional readings of the story as a cautionary moral tale of tragic, illicit love, Benjamin fore-grounded the opposition between human subjection to fate and characterful, decisive action, a contrast which serves as an instructive lesson in the need to contest rnythic forces. In particular, Benjamin contended, the protracted death of one of the miscreant lovers, Ottilie, presents the demise of beauty for a higher purpose, truth, and thus serves as an allegory of the task of criticism itself. In the early 1920s Benjamin hoped to make his identity in literary criticism by editing his own journal, Angelus Novus, the New Angel. Suspecting, however, that the erudite and arcane material would prove commercially unviable, the prospective publisher pulled out before the first issue was finalized. This bitter disappointment prompted Benjamin’s return to the academic sphere. He embarked upon his Habilitationsschrift at the University of Frankfurt, taking as his theme the seventeenth-century German play of mourning, the Trauerspiel. Dismissed as bastardized tragedies, these baroque dramas with their preposterous plots and bombastic language had long been consigned to the dusty attic of literary failures. Benjamin’s immanent critique of these scorned and neglected works distinguished them from the classical tragic form, and reinterpreted and redeemed them as the quintessential expression of the frailties and vanities of God-forsaken human existence and the ‘natural history’ of the human physis as decay. In so doing, Benjamin argued for the importance of allegory as a trope which renders and represents the world precisely as fragmentation, ruination and mortification. Benjamin’s Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels, with its obscure subject matter and impenetrable methodological preamble, baffled and bemused its inept examiners, and he was advised to withdraw it, rather than face the ultimate humiliation of outright rejection. By late summer 1925, his ambitions for an academic career lay in ruins. Benjamin was to remain an intellectual outsider for the rest of his life, free to lambaste and lampoon scholarly conventions, but at the same time utterly dependent on the good offices of publishers, the press, commissioning editors and others who, like Ernst Schoen at Siidwestdeutscher Rundfunk and Siegfried Kracauer at the Frankfurter Zeitung, offered what work they could. Benjamin’s growing friendship with Theodor Adorno, whom he met in 1923, led to an associate membership of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research and a small stipend; yet, his life was dogged by financial anxieties. The fragmentation and astonishing diversity of Benjamin’s oeuvre is a clear consequence of economic exigencies. Benjamin translated and wrote on Marcel Proust; he produced eloquent essays on such key literary figures as Franz Kafka, Bertolt Brecht, Karl Kraus, the Surrealists and Charles Baudelaire; he also penned a radio piece entitled ‘True Stories of Dogs’, a set of reflections on Russian peasant toys, and a review of Charlie Chaplin. Only this can be said of such enforced eclecticism: the least likely and most maligned of things always attracted his attention, and always provided his most telling insights.

Benjamin was never to write another book in the, for him, compromised, ‘scholarly’ style of his Trauerspiel study, which was eventually published in 1928. Instead, the aphorism, the illuminating aside, the quotation, the imagistic fragment became his preferred indeed, essential mode of expression. In presenting and representing the everyday in a new light, observing it from an unexpected angle, such miniatures were intended to catch the reader off guard like a series of blows decisively dealt, Benjamin once observed, left-handed. Starting with pen portraits of cities he visited (‘Naples’, ‘Marseilles’, and ‘Moscow’) and his 1926 montage of urban images, One-Way Street, Benjamin’s writings began to take on a more pronounced contemporary inflection and radical political colouring. While working on the Trauerspiel study on Capri in the summer of 1924, Benjamin had read Georg Lukacs’s History and Class Consciousness, and had been introduced to a Latvian theatre director, Asja Lacis. His enthusiasm for the former and troubled love affair with the latter drew Benjamin to Marxist ideas. In the winter of 1926-7 he visited Moscow to see the new Soviet system for himself. His initial enthusiasm waned in response to the indifference of the Soviet authorities, the impossibility of the language and, especially, the artistic impoverishment and intellectual compromises already discernible. Benjamin returned to Berlin, where, through Lacis, he met and became friends with the playwright Bertolt Brecht. To the dismay of Adorno and Scholem, who saw Benjamin’s always unorthodox, unconvincing espousal of Marxist ideas as a foolhardy flirtation, he became an advocate of Brecht’s ‘epic theatre’ with its blunt political didacticism. While Benjamin himself refrained from ‘crude thinking’, its traces and imperatives are evident in many of his writings during the 1930s on the situation and task of the contemporary artist (‘The Author as Producer’, 1934) and the character and consequences of new media forms for the work of art and aesthetics (‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, 1 935). Benjamin’s concern with the fate of art within capitalist modernity, with the Marxist critique of commodity culture, and with the character and experience of the urban environment were to combine in a project which was to occupy him from 1927 until his untimely death in 1940. Inspired by the Parisian perambulations of the Surrealist writer Louis Aragon (1987 {1926}), Benjamin embarked upon a study of the then derelict Parisian shopping arcades built in the first half of the nineteenth century. Initially modest in scope, Benjamin’s Passagenarbeit, or Passagen-Werk (‘Arcades Project’) was eventually to comprise more than 1,000 pages of notes, quotations, sketches and drafts, and today remains as an unfinished indeed, never written ‘prehistory’ of nineteenth-century Paris as the original site of modern consumer capitalism, a plethora of fragments providing a panoramic and kaleidoscopic exploration of the city’s fashions and phantasmagoria, architecture and boulevards, literature and politics. Significantly, it was to Paris, rather than to Moscow or Palestine, that Benjamin fled in 1933 to escape the Nazi terror. There he pursued his researches for the ‘Arcades Project’ in the Bibliotheque nationale, work which led to a proposed book on Baudlaire and a series of historiographical principles intended as a methodological introduction. Like the wider Passagenarbeit, these too were never completed. Despite the advice and efforts of Adorno and Horkheimer, then in exile in New York, Benjamin lingered too long in Paris, and was trapped in 1940 by the German invasion. He fled to the south of the country, was temporarily interned, and, once released, desperately sought an escape route. It was not to be. Benjamin attempted to cross into the relative safety of Spain, but was turned back at the border. Later wearied by his exertions, he was facing certain arrest on his return to France, Benjamin cornmitted suicide on 26 September 1940. He is buried at Port Bou.

Understanding of Life

Benjamin’s fragmentary oeuvre presents a highly eclectic and provocative combination of concepts, themes and motifs drawn from a distinctive and diverse set of sources: Judaic mysticism and Messianism; early German Romanticism; modernism and in particular, Surrealism; and an extremely unorthodox Marxism. His writings form a complex constellation with those of a number of friends and associates whose competing influences contribute to the highly paradoxical, ambiguous and elusive character of Benjamin’s principal concepts and arguments. His early ideas on language, translation and mourning were deeply indebted to his close and long-standing friendship with Scholem, who continually urged him to learn Hebrew and to devote himself to his ‘true’ calling: the esoteric domain of Jewish theology. Surprisingly, given the convolutions and intricacies of his own writing, Benjamin was drawn less to the enigmas and subtleties of the Kabbalah, and more to its very antithesis: the Marxist ‘crude thinking’ of Brecht, a writer to whom every hint of mysticism was an anathema. The gravitation of Benjamin’s thinking towards Brechtian didacticism in the 1930s was lamented not only by Scholem, but also by Horkheimer and Adorno, as the most needless self-betrayal. Horkheimer and Adorno wished to claim Benjamin for their own camp a Critical Theorist and dialectician of the highest order and tried to persuade him to eliminate frorn his work not only Brechtian elements, but also concepts drawn from other writers who did not meet with their approval. It was supposedly behaviourist aspects of Silnmel’s urban social psychology for example. As a result, their treatment of Benjamin’s writings was not always benign, as exemplified by their editorial intransigence and interference vis-a-vis the Baudelaire studies of the late 1930s. Benjamin’s work exists in a complex interplay with the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School. Of all the writers associated with the Institute, it is Kracauer who in many ways demonstrates the closest thematic and conceptual connections: a fascination with the city, urban architecture and flanerie; an appreciation of film and popular culture; a privileging of fragments and surfaces; and a preoccupation with Parisian culture during the Second Empireto say nothing of Kracauer’ s later historiographical interests. Benjamin and Kracauer saw much of each other – they were in the same places at the same time (Frankfurt in the mid-1920s, Berlin in the early 1930s, Paris from 1933) and they reviewed each other’s work with some enthusiasm.

Conclusions

Axel Honneth claims that despite the intensity of the scholarly debate over the meaning of his texts, Benjamin’s writing is largely irrelevant for contemporary philosophical research. The writing, in Honneth’s words, strongly resists theory formation. The debate it engenders is thus akin to a stake-less dispute over the literary interpretation of a text and it is of possible interest and consequence only to its immediate participants. Hence, it does not pretend to provide an all-encompassing, exhaustive introduction to Benjamin’s work, but offers instead what I hope will be an engaging, illuminating examination of a selection of his major writings, themes and concepts. It is an investigation which serves, above all, as an invitation to read and explore both the texts discussed here and Benjarnin’s wider oeuvre. Walter Benjamin’s idea of revolutionary experience, as well an instructive point of contrast between Benjamin’s treatment of this idea and other well-known conceptions of revolution. Benjamin’s insightful conception of revolutionary experience was not able to solve the historical puzzle of a new form of collective experience. But, for this very reason his way of placing revolution in the context of the seemingly irreversible shift away from collective tradition to individual experience retains its perspicacity today.

References

- Arendt, H. (2006). On Revolution. London: Penguin.

- Benjamin, W. (1972–1991). Gesammelte Schriften (R. Tiedemann & H. Schweppenhäuser, Eds.). 7 vols. Frankfurt A.M.: Suhrkamp.

- Benjamin, W. (1996–2003). Selected Writings (M. P. Bullock, M. W. Jennings, H. Eiland, & G. Smith, ). 4 vols. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Benjamin, W. (1998). The Origin of German Tragic Drama. (J. Osborne, Trans.). London: Verso.

- Benjamin, W. (1999). The Arcades Project. (H. Eiland & K. McLaughlin, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Caygill, H. (1996). Walter Benjamin: The Colour of Experience. London: Routledge.

- Freud, S. (1985). Letter to W. Fliess 28 May, 1899. In J. M. Masson (Ed.), The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887–1904, 353. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Friedlander, E. (2012). Walter Benjamin: A Philosophical Portrait. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Honneth, A. (1993). A Communicative Disclosure of the Past: On the relation between anthropology and philosophy of history in Walter Benjamin. In L. Marcus & L. Nead (Eds.), The Actuality of Walter Benjamin. New Formations (No. 20, pp. 83–94). London: Lawrence and Wishart.

I Pravat Ranjan Sethi finished my studies from Centre for Historical Studies, JNU, New Delhi, at present teaching at Amity University. The keen area of interest is Modern History in particular Nationalism, Political History& Critical Theory and Social Theory.