शिळेखाली हात होता, तरी नाही फोडला हंबरडा

किती जन्मांची कैद, कुणी निर्मिला हा कोंडवाडा……’

-दया पवार

The above lines taken from Daya Pawar’s poem ‘ kondwada’ essays the inner nuances of the struggle of Dalits to achieve their dream of the egalitarian society which shall be based on the edifice of Genderless, Casteless and Classless Society.It also potrays the hope and aspirations that Dalits have in their struggle and faith in the dream of instituting an utopia where equality in all realms shall be a normal and their readiness to bear humilation and sacrifice come what may !

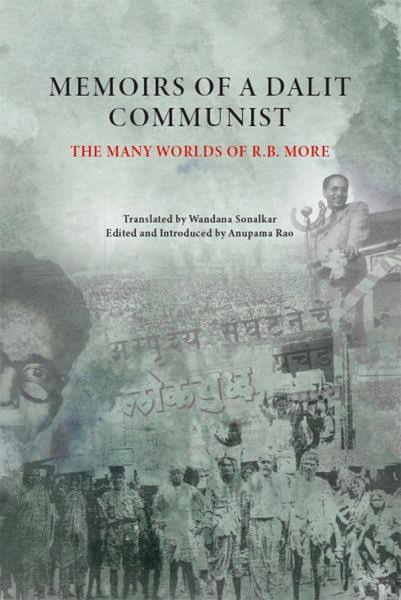

This autobiography/biography of R.B.More, a Dalit communist, bridges the divide between caste and class in ‘Snub-nosed’ Mumbai’s historiography to use the phrase of ace poet Namdeo Dhasal.It potrays a inherent divide that is a product as much of history as of scholarship. It brilliantly peeps into the etymology and epistemology of the connections between, and the impediments to, the twin struggles for class emancipation and Dalit liberation. With a superb introduction by Anupama Rao that sets More’s life and struggles in the historical context of the city,which sings its own saga, the text provides a rich picture of the social, cultural,economical and political meanings of what it meant to be a Dalit and a communist. This is an indispensable contribution to the literature on Mumbai’s history after Amar Faruqui’s masterpiece.

R.B Moré begins the narrative of his life in Ladawali, during the celebration of the Chabina of Viroba, consciously intertwining geographic space and the events of his life with anti-caste discussion. He describes how untouchability was not practiced during the procession where most of the gods were carried by Mahars like him, a procession that was also taking place at the time of his birth. It also puts forth the critic of Bhakti Movement where Equality was only in the Bhakti phase and real life consisted of point blank practice of Discrimination, thus putting forth the “Saguna Bhakti” dictum as opposed to ” Nirguna Bhakti” as noted by Scholar Christian Lee Novetzke.This engagement also suggests that Moré wants us to read his text as a critique of untouchability, a sentiment mirrored in the very first sentence: “The first capital of the Marathi state in modern times was Raaigad. It was in the village of Laadawali in the precinct of this same Raaigad that I was born, at dawn on a Sunday on the second day of the lunar month, in the year 1903 C.E. The night of the Chhabina of Viroba at Mahaad was drawing to an end”. The quote performs a number of symbolic associations between Moré and Ladawali that establish his tone of critique: by saying he was born on “this same Raaigad” that was the first capital of the Marathi state, he establishes himself as an inheritor and continuator of the political centrality of Raaigad to Maharashtra in relation to Dalit activism, receiving and expanding the tradition of anti-caste thought in the region. Furthermore, with “The night of the Chhabina of Viroba at Mahad was drawing to an end,” he is also associating his very birth with a suspension of untouchability.

The decision to start his memoir with the Chabina of Viroba also offers us the possibility of looking at the absence of untouchability during the procession from a perspective other than religious practice. It invites us to also look at spatial organization. If the procession is anything like how it is practiced today (see the “Chabina of Viroba Today” marker on Ladawali), one can see that the density of people that attend and the need to walk through a space that can only hold a limited amount of bodies would have made it quite difficult for untouchability to be maintained. Just how in Bombay during this time period rural, Dalit migrants escaped untouchability due to the constraints of the infrastructures of transportation and communication that forced bodies to be in close proximity of each other, the lack of untouchability in the procession might also relate to space itself.. Looking at spatial organization allows us to raise the same questions which josue cjavez asks: How is the process of urbanization that Moré implicitly describes in his text (a process he is a part of given his constant migration between villages and Bombay) allowing him to combat precarity while simultaneously appropriating his actions and entrenching the conditions of marginalization the memoir is so explicitly against? How can a visualization of More’s memoir as a proxy for the dynamics of rural-urban migration help us see not only the dispossession of people from rural land but how their actions (often directed towards improving their lives) become appropriated for the reproduction of marginalization and its implied socioeconomic relations?

Professor Rao’s introduction of R.B. More (1903-1972) is an important addition to this jewel by highlighting More as an under-acknowledged Dalit trade unionist, labor organizer, and Ambedkarite.Her narrative also takes us back to conversations between Ambedkar and Marx, and between caste and class as these played out in Bombay’s working class neighborhoods.She points that R. B. More’s account suggests a crucial link between Dalit urbanity and Bombay’s distinctive public and political culture, reiterating More’s line of questioning of political utopia and life writing by focusing on particular themes that emerge with particular force and vitality in More’s account: mass intellectuality; housing and homelessness; pleasure, performance and wayward lives; and finally, the figure of Ambedkar

The autobiography potray various inner nuances of the praxis of Ambedkarite and Left Movement in India along with crucial episodes highlighting R.B. More’s leadership in Babasaheb Ambedkar’s movement, his role as a trade unionist and a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). More’s life, narrated in his words and those of his son Satyendra, illuminates the conflict between the promise of Marxist emancipation and the hard reality of the hierarchies of caste. His radicalism challenged both the limits of the politics of caste and the politics of the Left; his was a politics that frontally challenged the rigidities of the caste system and of the class structure. This memoir, written in Marathi, is here published for the first time in English brilliantly translated by prof.Wandana Sonalkar is a rare work that brings together family history, political thought, and the social experience of urban workers whose lives are intertwined with the city they built, Bombay where collaboration takes place amongst marginalized subjects in order to lay their claim on space, survive through the physical, emotional and psychological distress caused by caste discrimination and poverty, and as a way to make their dreams and aspirations come true. Reading the memoir as a story of people as infrastructure allows us also to think about the disposition of such infrastructure. It is a way to visualize the invisible yet stubborn forms of power behind the infrastructure that re-appropriate Moré’s actions to inflict dispossession along axes of power that Moré’s imaginary of reform cannot account for.Though his activism forefronts class-caste but it fails to take into account gender and other bodies that are constructed as undesirable through the mobilization of notions of morality and respectability.

To sum up it More’s account entails that there is stark separation between social morality, idea of social inclusion promised by Constitutional Morality and the envisaged Idea of India.It forces the reader to critically engage with all the entities which are needed to be made keeping in mind the basic and most important objective i.e instituting “Begumpura”which shall not be a land of mass with the populace divorced from nature but living with the fullest essence of liberty,equality and fraternity trio in a balanced state and where people shall not feel that their birth is a fatal accident but an event of joy,abundance with the Societal “void” as potrayed by French philosopher Alain Badiou to be filled by Love and Dignity transcending all boundaries as evident from life and struggle of Dr. B.R Ambedkar.

Adv.Nikhil Sanjay-Rekha Adsule has completed his B.E(Electrical) and pursued Masters in Law from TISS, Mumbai.He has Masters in History too along with NET(JRF) and SET.He is currently pursuing another Masters in Women and Gender Studies.He is recipient of prestigious Dr. Ambedkar National Dignity Award-2019.He dreams of creating a BEGUMPURA of Genderless,Casteless and Classless India.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER