Part I: The Life-Changing Rabindra-Sangeet He Revealed to Me

I was born in a post-renaissance, post-independence Bengal, in the city of Kolkata (erstwhile Calcutta from colonial times), at a time when the Bengal Renaissance, which began with Raja Rammohun Roy (1774-1833) and many would argue reached its zenith with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), was beginning its gradual descent into mediocrity (in no small measure due to the deep wounds of partition and the associated displacements and mass deaths, and also the transfer of India’s national capital to Delhi in the early decades, and the attendant loss of political influence).

During my very early years, growing up in a deeply idealistic household with a Mother who (despite not having any college degree) was a relentless reader of books, big and small, anywhere and everywhere, and keenly observant of events around the world long before our current information age, and a Father who had spent five years of his young life as a freedom fighter in a British detention center, thereby sacrificing career pursuits for financial and material security- glimpses of what the staggering 150 or so years of Bengal’s immediate past history meant in virtually every imaginable field, were being brought to my brother and me on a daily basis. Those early growing years, we were not even in Bengal- as an employee in the Central Government’s Department of Statistics, my Father was posted in Allahabad in northern India- a city in the Hindi-speaking part of India which was 550 miles from Kolkata. And yet, Bengal was perpetually within our grasp (even as my parents taught us the importance of diverse languages, cultures and people), such was their natural affinity for anything Bengali. For them, it was not even a conscious choice- it was simply a part of our daily lives, far from the province of our origin, whose revitalizing influence on them was evident every day, in every way.

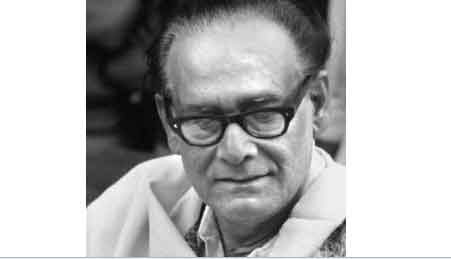

Despite my Father’s very modest means in those years, our home was never lacking in cultural stimuli- we subscribed to the incomparable Bengali weekly (literary) periodical, Desh (which in my opinion has as glorious a history of sterling authors and scholars as anything The New Yorker boasts about, and I have perused both over extended periods of time) for as long as I can remember, and from the pages of which my Mother would read us articles during the years we were barely honing our Bengali reading and writing skills. We also had the newspaper-boy drop off the northern Indian print edition of Ananda Bazar Patrika, Bengal’s leading newspaper, every day. The headlines and photographs on every page of that paper brought Bengal home to us instantly, even as my brother and I rapidly consumed all the comic strips (translated to impeccable Bengali by hugely talented individuals from the remnants of the renaissance) and then the sports pages- football, to tennis, to cricket, to snooker, to chess. And we had an older valve-based radio set (an Ultra, my Father would tell us) which picked up All India Radio, Calcutta remarkably well. And it is how, through the music propagated into the airwaves through this Ultra that the captivating, irreplaceable voice of Hemanta Mukhopadhyay (hereafter HM) captured my young imagination and made it indelible for life- this will be one of the starting points of the 5-part essay I plan to write about this genuine “Baritone of our Renaissance” on the occasion of his centennial year.

This is not intended as a biographical essay; I can only hope that someone who feels just as indebted to HM for the introduction to, and identification with a Bengali musical identity will create an appropriate biographical tribute. My purpose for this centennial remembrance is to provide introductory sketches of HM’s contributions to Bengali vocal music during an era rightly regarded as the golden age (late 1940s through mid-1970s) of that genre which may be perceived as an appropriate follow-up to the renaissance creativity of poets and composers with Rabindranath Tagore at the very crest.

With that in mind, I will therefore begin in this Part I with HM and his contributions to Rabindra-Sangeet (the Bengali terminology for the songs of Tagore which are the single greatest identifier of Bengal’s renaissance musical culture), specifically with references to how his voice and style made Tagore’s music literally come alive inside my own mind

In my very early, pre-teen years in Allahabad, two voices primarily established Rabindra-Sangeet as a supremely elevating musical creation with an unsurpassed blend of lyrics and melody, the lyrics being both poetically sweeping and also imaginative and inspiring- these two voices belonged to Suchitra Mitra among the female singers and of course, HM among the male. For me in those early years, it was these two with the sage-like Pankaj Mullick as the connecting arch. My earliest recollection listening to HM singing a Rabindra-Sangeet had to do with several of his extraordinary renditions of Tagore’s Swadesh songs (dedicated to the Motherland). I have since listened to several of the other exemplars of these songs, some of whose works approach a similar level of inspirational value, yet HM remains to this day for me the gold standard against which the others are invariably evaluated.

Hemanta Mukhopadhyay was not trained as a classical vocalist, unlike many others who rose high in the pantheon of Bengali and Indian music (especially those in the category of the emerging genre of modern songs)- and for this reason his work sometimes has tended to be if not derided outright, considered lesser relative to others trained in the structural aspects of classical ragas. To my equally untrained ear, however, the melody and lyrical content of his baritone, with the balance of sweeping notes and volumetric tonality- made listening to HM an absolute treat for my auditory senses.

In this article, I will discuss ten of HM’s large compendium of superlative Rabindra-Sangeet, a small number intended to provide a glimpse into the lasting value of these songs in my life. We must also bear in mind that following Tagore’s passing in 1941, Visva Bharati, the institution he created for dissemination of his vision of education and culture, held an exceedingly tight leash upon performances of Tagore’s songs, and many an artist would languish in the shadows without the permission or authorization from the Visva Bharati Music Board. It is rather remarkable, then, that all those decades ago, despite such strangle-hold by the music board on the style and rendition of the songs relative to the Poet’s approved notation, HM even as an outsider received approval from the same board! I definitely believe in this instance, by offering HM their approval, the board made the correct determination.

Of the ten in the sampler, two are of the Swadesh or Homage to the Motherland category, four from Puja or devotional, and the remaining four from Prem or Romance and Vichitra or Intrigue. Several from the much wider range of HM’s Tagore songs will have been left out from this discussion.

Homage to the Motherland / Swadesh

My true formal introduction to both Rabindra-Sangeet, and also to HM as a resonant, mellifluous vocalist occurred via his rendering of two songs in particular (there were others which will not be covered here), O Amar Desher Mati, and Ayi Bhuvanamonomohini. As much as Rabindranath Tagore holds the virtually unmatched distinction as the author/composer of two national anthems (India/Bangladesh) and the inspiration behind a third (Sri Lanka), I would like to contend these two songs could easily vie for that distinction (also, there are some Tagore compositions which in my opinion could be considered anthems for the Earth). And in HM’s absolutely soulful rendering, they find new meaning- to the extent that even 4 or 5 decades later, I am just as moved and filled with devotional wonderment the same way as when I heard them first. I will let the words and HM’s singing speak for themselves. Here is a prose translation with the YouTube link:

Beloved Soil of My Motherland (O Amar Desher Mati)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2020

Soil of my beloved land, I bow my head to you.

Upon you is spread the anchal of she who permeates all

She who is the Universal Mother.

Soil of my beloved land, I bow my head to you.

You have entered my flesh and blood, mingled with my heart and soul

Your gentle, verdant and tranquil image is etched upon my being-

Soil of my beloved land, I bow my head to you.

Mother- in your lap was my birth, in your embrace, too, shall be my end

Upon you, Mother, my play forever in happiness and sorrow.

You assuaged my hunger with nourishing grains,

With cool water quenched my thirst

You are the all-enduring, ever tolerant Mother of Mothers.

Mother, I have partaken much of your bounty, and received beyond measure

Yet I know not what I have ever given you back in gratitude!

My life, Mother, has been spent in aimless pursuits

I spent my days whiling away my time within my four walls

O source of all strength- in vain, alas, you vouchsafed to me my strength.

Anchal: the flowing free end of a sari, usually cascaded over the shoulder.

The next song, Ayi Bhuvanamonomohini, was included among the prayer songs performed at Mahatma Gandhi’s prayer gatherings. Cynthia Snodgrass used the version below as translated by this author in her dissertation, Sounds of Satyagraha (2011).

Peerless, Alluring Enchantress (Ayi Bhuvanamonomohini)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 1992

Peerless, alluring enchantress of the Earth!

Pure, serene, sun-drenched- ageless Mother of all.

Feet awash in the blue waters of Sindhu,

Verdant anchal swaying gently in the breeze-

Mighty Himachal, your vast forehead

Peaks capped in virgin snow, lofty and majestic

Rising to kiss the sky!

The first Dawn, dispelling all darkness-

Appeared in your skies;

The first glorious chants of Sama tunes

Arose from your forest hermitages;

From your woodlands and hamlets

Transmitted near and far-

The first words of Wisdom, Dharma,

Epics and fables of inspiration.

Ever-benevolent Mother, glory, glory be to you-

Feeding the hungry at home and abroad;

The waters of Jahnavi and Jamuna,

Streams of molten compassion

Carry from your breasts

The blessed nectar of eternal life!

Himachal – another name for the Himalayas.

Sama – holy chants from Vedic India, sung in hermitages.

Dharma – Hindu concept of the righteous path.

Jahnavi, Jamuna– holy rivers (Ganga and Yamuna) in India.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5m8QdqU328

Prem / Romance and Vichitra / Intrigue

The next two Tagore songs have a very special place in this author’s teenage memory. After my brother and I had relocated to Kolkata (1968) from Allahabad following a crushing family tragedy, the Ultra radio set found a new place on a wall shelf in my Father’s room inside my grandparents’ house. I recall sleeping every so often on a twin bed next to the farthest wall from the overhanging veranda, and directly across from the shelf with the radio. I will never forget the ethereal mornings I would be awakened before 7 am by a variety of early morning programs on All India radio (AIR), Calcutta. Those culturally deep and vibrant programs have become permanently etched in my memory, and I will write more on them in a different forum. But let me point out that the two Tagore numbers which follow were among several sung by HM which brought out the glorious radiance of dawn via Tagore’s immortal words- creating an almost other-worldly joy, marveling at the joy permeating the human soul every time a brand new day is gifted to us via sunrise, birdcalls and myriad sights and sounds of the living world. I feel eternally grateful that dousing my spirit in these songs each morning was my very own special treat in the growing years, and that the treat was offered by Tagore via the divine voice of HM. Eons from now, in any other incarnation, I would forever wish to be awakened by these songs, performed by none other than Hemanta Mukhopadhyay. With Rabindranath Tagore, he made me feel irretrievably proud to have inherited even a small part of this renaissance.

Sweet and Somber the Beckoning (Dhwanilo Aobhano Modhuro Gombhiro)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2020

When your melody awakens me from slumber

My slumber feels touched by the deepest love.

That slumber is on the obverse of my wakefulness, may she ever

Receive your dream-like touch.

Unfathomably deep its hunger, secret its hankering for sweet daylight

Dwells upon the expanse of my night, and yet beloved it is

Of your morn.

For her the sky turns scarlet in the darkness-dispelling blush of dawn

It is for her the songbirds carry alaap tunes of hope

Then your quiet, inaudible footsteps play for her the tunes of agamani

She is the bud of eventide, pluck her at daybreak.

alaap – a segment near the beginning a classical Indian vocal or instrumental rendition which sets the tone for the ensuing raga or melodic theme.

agamani – a genre of Bengali devotional songs based on folk traditions which re-tells the story of the goddess Durga arriving home from her celestial abode to be with her human family.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02gBRlW8xLk

And along with several others, here was another morning song which filled my entire day with gladness.

Awaken Amid Renewed Bliss (Naba Anonde Jago Aji)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2020

Awaken, today, amid renewed bliss, awaken to the radiant sunbeams

Awaken to pure beauty, grace and goodwill, awaken to an immaculate life.

May a new wellspring gush out of life, and songs of ecstatic hope fill the air

May the gentle breeze carry this day the ambrosial fragrance of heavenly blossoms.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJfLMEzVPow

The two songs which follow are also from my early years in Kolkata. These ethereal creations penetrate deep into the very core of our conscience- the uplifting quality and the sheer ecstatic humanity of these cannot be expressed in words, much less in the hugely approximate English renditions of the divine originals. The first of these has a personal anecdotal history which appeared in my collection, Seasons of Life. Here briefly is that anecdote. This translator recalls singing this song once before an audience at the Indian Institute of Technology; a while later, one of his batchmates from outside Bengal spoke to him and confessed how much the words and emotions expressed by Tagore in this song had moved him deeply.

My Friend, Beloved of My Heart (Shudhu Tomar Bani)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2014

My friend, beloved of my heart

I crave not the comfort of your words alone-

Every now and then, grant me

The comfort of your touch.

Weary from traveling the long road

Parched and dehydrated all day-

I wander aimlessly searching for a shelter

To rest my bones and quench this thirst.

Tell me, my friend, assure me

This darkess finds its fulfillment in you.

This heart of mine yearns to give

And wishes not simply to receive

It carries everywhere

The burden of its accumulation

Its gifts to give away.

Extend to me your hand, beloved

Place it on mine-

Allow me to hold it, fill it with my gift of love

Keep it by me like a secret treasure-

Make my lonesome journey, at long last

A romantic pilgrimage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bPvw3bI6Q3c

Beyond the fact that the following song by HM, which was one of several from my teen years, culled from Tagore’s Puja and Prem numbers which absolutely enchanted me (and still does), I have to mention that by singing this one for my hostel seniors at the IIT in 1974, I was able to avoid the tyranny of “ragging” or hazing of freshmen then quite prevalent.

When All My Doors Lay Shattered (Je Raate Mor Duarguli)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2014

That night, when all my doors

Lay shattered beneath the path of the raging storm

I knew not then, it really was you who entered my room.

The light of my flickering lamp went out

And darkness swallowed everything;

Helpless, I stretched my arms skyward

Looking for someone to hold me-

I knew not then, it really was you who entered my room.

I lay prostrate in the dark, thinking it was a nightmare-

Not knowing the howling wind was your victory-ensign.

When morning came, and I awoke-

It was you I saw standing tall

Atop the vast emptiness of my room.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3FOGGVaRyM

The next song, a blend of nature, mystery and romance, is one of several by HM which go back to my years in Kolkata. This one is 100% the quintessential Hemanta Mukhopadhyay, never to be replicated.

On the Branches of the Shirish (Prangane Mor Shirish Shakhay)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2014

On the branches of the shirish

In my garden this Phalgun

Tireless bloom the spring blossoms-

Until the day fades away,

The birds stop cooing, and quiet befalls at twilight.

Ah, a year ago on a day like this

The shirish branches caught a frenzy of dance

In springtime, inspired by the tinkle

Of dancing feet in heaven.

And ever since, when spring was gone,

That restless spirit oft inquired of me:

Has he not returned yet?

On other spring days like this one

Anxious and hopeful, the branches listen

Intently, for the subtle, intangible footsteps

And daily, faith undying,

They whisper in soft murmurs

Is he, then, on his way?

And now, this flower-enamored Phalgun

With what assurance might I ask,

O night star of my destiny

Will my counting of fleeting instants never be over?

And each day, across my garden, distraught

The wild wind sighs, Tell me,

Is he here, is he here?

The next song is frequently requested or sung at informal Bengali gatherings, especially at moments of remembrance of a loved one. As with several other compositions, Tagore identifies with the withered, the downtrodden, the fallen and the marginalized in life (in several songs, this appears as fallen leaves, dry grasses and barren forests.

I Entreat You, Forget Not (Ei Kothati Mone Rekho)

Translation © Monish R Chatterjee 2014

This, I entreat you, forget not

Somewhere between your laughter and play

That I once sang my songs

In the season when the withered leaves fell.

When the grass was dry

And the forest barren

Lost in my own world, amid neglect and abuse

Forget not I sang my songs.

Forget not, O traveler of daytime

My journey was in the dark of night

A flickering oil-lamp in hand.

Then, when the call came for me

From the other shore

And I went afloat on a leaky raft

Forget not I sang my songs.

And next in the sequence is another song of remembrance highlighting the importance and value of every single life which has had its play upon this exemplary laboratory of life- it sums up the human experience as a series of interplays between discord and melodies, silence and treasured words, the tradeoffs at the marketplace, the memories that remain at play’s end.

Jokhon Porbe Na Mor Payer Chihna

When my footprints fall no longer upon this field

And I no longer row my boat to this shore;

I will have then finished buying and selling my wares

And balanced the ledger of what I owe and am owed-

My journeys to this marketplace will be over.

It’s fine, dear, if you remember me not then-

Gazing at the stars, it’s fine if you do not call me.

When dust shall cover the strings of the tanpura

Thorny creepers cover the doorways, aha,

Dense wild grasses stifle the exiled flower garden,

And algae smother edges of the pond-

It’s fine, dear, if you remember me not then-

Gazing at the stars, it’s fine if you do not call me.

Then, too, the flute shall play in this theater just like now,

The days shall pass, indeed, the days shall pass

As they do now, aha,

The ferryboats shall fill up just like this at the riverbanks-

The cows will will graze and cowherds play

In the meadow yonder.

It’s fine, dear, if you remember me not then-

Gazing at the stars, it’s fine if you do not call me.

Who says I am no longer there at that dawn?

I shall be a player in every game that day- aha,

They shall call me by different names, bind me

In new embraces,

Coming and going, forever, will be the eternal me.

It’s fine, dear, if you remember me not then-

Gazing at the stars, it’s fine if you do not call me.

Finding ten Tagore songs out of the many dozens in the HM compendium is a truly futile exercise- many absolutely stirring numbers come rushing to my mind. Here is one probably from the latter part of HM’s 40+ years at the forefront of the golden age- this was a duet (of which HM did not have many in the Rabindra Sangeet genre) with a young Haimanti Sukla. I have used this song with its exhortations to the Creator to awaken to life from the coldness of death enlivened by the tunes of a song.

This is the Boon I Ask (Tomar Kachhe E Bor Magi)

This is the boon I ask of you-

That I may awaken from death

By the tunes of a song.

When I open my eyes-

Like nectar from mother’s breast

May I be filled with fresh new life

By the tunes of a song.

In that new world trees and reeds

Rise up from the great flute of the earth

Like the tunes of a song.

There heavenly light brings the tidings

Of the boundless joy of the sky-

Lingers in the depths of the heart

Stirred by the tunes of a song.

MP3 URL: https://gaana.com/song/tomar-kachhe-e-bor-magi-5

Follow-up parts of my remembrance of Hemanta Mukhopadhay at his Centennial as a personal journey through my own life will appear in the weeks ahead.

Dr. Monish R. Chatterjee, a professor at the University of Dayton who specializes in applied optics, has contributed more than 130 papers to technical conferences, and has published more than 75 papers in archival journals and conference proceedings, in addition to numerous reference articles on science. He has also authored several literary essays and four books of literary translations from his native Bengali into English (Kamalakanta, Profiles in Faith, Balika Badhu, and Seasons of Life). Dr. Chatterjee believes strongly in humanitarian activism for social justice.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER