The spectre of eviction has continued to haunt the peoples of the Sundarban forests since the colonial times, if not since even further back. Come circa 2024, and this spectre has turned into Damocles’ sword. More than 1 lakh fishers face eviction in the Indian part of the Sundarbans as I write this.

Over 2 million people subsist on the Indian Sundarbans. Depending on seasonal variations in livelihood patterns, this number can be higher than 5 million. And this is based on the 2011 Census data. There is no telling if the number has increased, decreased, or remained the same. Varying patterns of rising out-migration, affected further by the phenomenon of ‘distressed reverse migration’ as observed onset and spread of Covid 19 and its consequent lockdowns, make it impossible to estimate the exact number of people in India who live close to the Sundarban forests and depend on the forests for their survival and sustenance.

Nonetheless, there can be no denying that anything between 1 to 1.5 lakh fishers depend on the Sundarbans for their livelihood. Likewise, there can be no denying that all these people are facing grave and imminent peril of eviction from their traditional geographical areas of livelihood on multiple counts. Let’s see how and why. But, let’s first look at the lives and livelihoods of the people who are facing this eviction.

Forming fishing-teams constituting three, four or five persons, the traditional small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans go out on seasonal fishing expeditions in the marine and estuarine waterways of the Sundarbans. The boats they go out on are non-mechanised – called ‘dinghy’ or ‘dinghee’ in local parlance – a word that had crept into the English language from South Bengal during the colonial times. They take turns to manually pull the oars, coursing through the tidal waterways of the Sundarbans, collecting fish, crab and at times honey.

The number of days during which a fishing team stays out on their dinghee-boats in the waters of the Sundarbans is determined by them based on the season, weather, climate, availability of fish-stock along the routes, etc., and through customary calculations based on tidal activities and the lunar calendar. For example, July 31, 2004 was the 11th day of the lunar fortnight, known as Ekadoshi in Bangla. On that day, many fishers from the Sundarbans have gone out or have tried to go out on fishing expeditions for their livelihood. They will fish in the waters of the Sundarbans for, what is known in Bangla as a ‘Gan’, pronounced as ‘gawn’.

‘Gan’ does not denote a specific number, but is a unit of measurement of the time spent journeying on a boat in relation to the distance covered and on lunar and tidal factors. (p. 766, Column 1, Bangiya Shabdakosh by Haricharan Bandyopadhyay, Sahitya Akademi, 1978 Reprint Edution). In the pre-colonial times, boat was a primary mean of conveyance in south Bengal, as it continues to be in the Sundarban delta.

Various ancient and medieval verses such as the Charyapada, the Dharmamangal, Manasamangal – attest to this usage of the word Gan in Bangla and proto-Bangla literature since at least the Pala era till the onset of colonial rule over Bengal. This word has since fallen out of usage in the baboo-Bengali bhadralok-parlance of modern-day Kolkata, swathes of which used to be a part of the Sundarban mangroves till at least the last half of the 18th century. Instead, it continues to be a word connected with the livelihood and of the few lakhs of small-scale fishers on the Sundarbans. For them, it is a very familiar and important word.

Coming back to the question of the time period for which the fishers can stay and pursue their livelihood, it is pertinent to note that the forest department usually issues a 42-day permit. In practice, it is seen that most fishing teams in the Sundarbans catch fish and crab in the forests for a few weeks to a month or so. One of the primary impediments to their traditional livelihood is posed by the license-permit raj that prevails in terms of governance in and of the Sundarbans.

Permits to enter the forests are issued only to those fishing teams who can show a curious document called the Boat License Certificate (BLC). The forest department has been unable to come up with any legal or administrative source-document to establish the validity of these BLCs. It has merely given a list of 923 BLCs that it had given, of which nearabout 700 are active. In local parlance, these are called ‘Tiger BLC’s.

Some sources indicate boat registrations done between 1923 and the mid-1940s leading to the evolution of these Tiger BLCs. Popularly prevalent oral hearsay, bordering on mythmaking, refer to some such certificates being given in the 19th century by the Dalit businesswoman Rani Rashmoni (1793-1861) who had a thriving fish trade along the riparian routes of southern Bengal.

In reality, one dinghee-boat cannot accommodate more than 4 or 5 fishers. When we look at the prevalence of nearabout 700 BLCs in a place like the STR where more than 1 lakh traditional small-scale fishers seek to pursue their traditional livelihood, and where more than 10 lakh dinghee-boats operate seasonally, the gap between demand and supply becomes clear. This disparity has led to the growth of a shadow economy around the marine fishing sector of the Sundarbans.

More than 500 of the 700 BLC-holders do not go for fishing themselves. They rent their BLCs out. As the situation has come to be, BLCs go through a series of subletting and middlemanship. Because of this, the illegal rent prices have skyrocketed. Ultimately, a team of small-scale fishers needs to come up with around Rs. 1 lakh or nearabout so to rent a BLC before they can get a forest-entry permit based on the same.

For instance, Sachin Mondal and his friend Rashid Gaji from Songaon, both traditional fishers hailing from a village in the Gosaba administrative block of the Sundarbans, were told to come up with a hefty amount of cash by the BLC-owner from their village. Being unable to do this, they have not been able to go into the Sundarban forests for fishing on the Gan that begun on 31st July, 2024 – Ekadoshi as per the vernacular lunar calendar.

Even for their friends and neighbours who could go, their journey has not been smooth sailing. The small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans live well below the poverty line and hail from historically oppressed communities. It is difficult for them to come up with Rs. 1 lakh to procure a BLC on rent, even if they split the expenses among three or four of them who are to constitute a fishing team. There are other initial investments required too – provisions of salt, ice, fuel and gear are required to be there in the boat during their fishing Gan, which can last from a fortnight to a month or so.

To afford these costs, the small-scale fishers need to take out advance loans from the Arotdars. As stockists, merchants and commission-agent, Arotdars have formed a key interface between fishers and farmers on one hand and the consumer market on the other, since pre-colonial times. According to Bongiyo Shabdokosh, Haricharan Bandyopadhyay, 1966, the word Arot is also present with the same meaning in the Maithili, Hindi, Sindhi, Gujrati and Marathi languages.

Traditionally, the Arotdars offer a form of earnest money or pledge money, known in vernacular Bangla parlance as ‘dadon’ – a word originating from the Farsi term ‘dadni’. The system of dadans has also existed since pre-colonial times, whereby such commission-agents or other middlemen used to offer the initial amount of money required for farming or fishing to landless farmers or tenureless fishers. Exploitative extraction leading from dadan-pledges offered by indigo commission agents was one of the primary factors that led to the Indigo Resistance (1859-1862) of Bengal

Needless to say, the small-scale fishers who take dadon-loans from the Arotdar have to repay the same – traditionally by giving them one-thirds of the fish and crabs collected from the Sundarban-waters. Rampant loan-sharking affects the vulnerable fishers massively. According to Nishith Gayen, a traditional small-scale fisher from Chhotmollakhali, a forest-adjacent village in the South 24 Parganas, his family needs to earn at least 2 or 2.5 lakhs every year to sustain themselves and maintain a bare minimum of dignified life. Rising BLC-rents and corresponding rising dadon-amounts are sharply eroding their livelihood security. As is the continual expansion of the core area and consequent reduction of the buffer region of the STR where the fishers are allowed to fish by the forest authority, added with the realities of relentless and unchecked tourism, cargo and fly-ash carriage activities in large dilapidated marine vehicles, and large-scale trawler-based commercial and mechanised fishing, which have reduced the fish-stock in the buffer-region drastically.

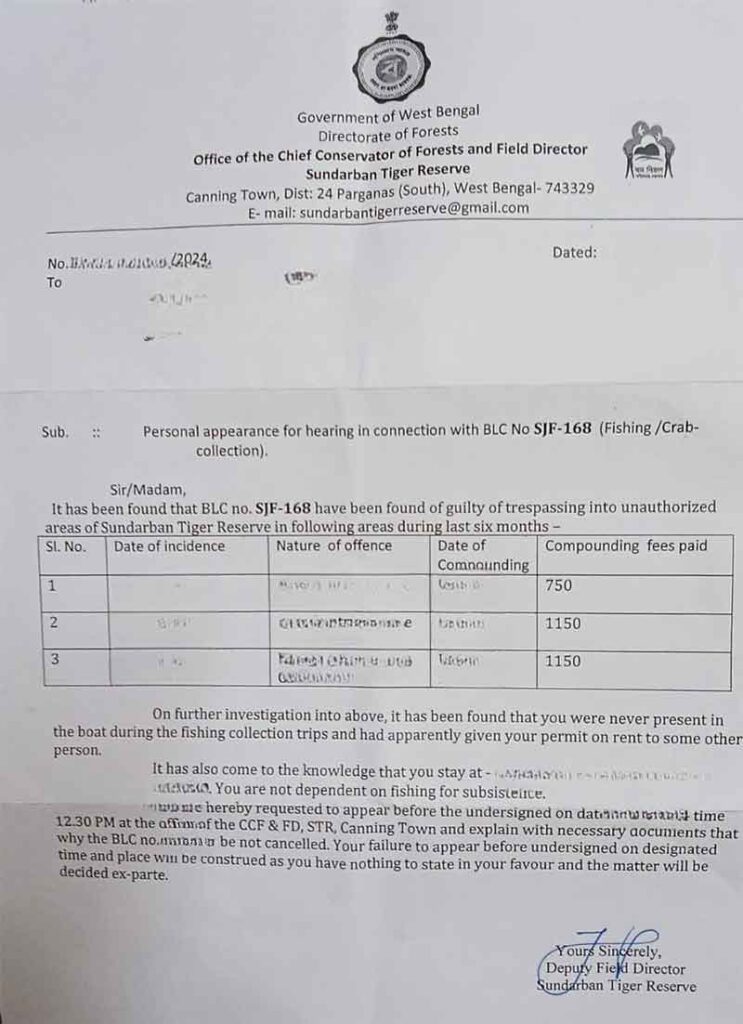

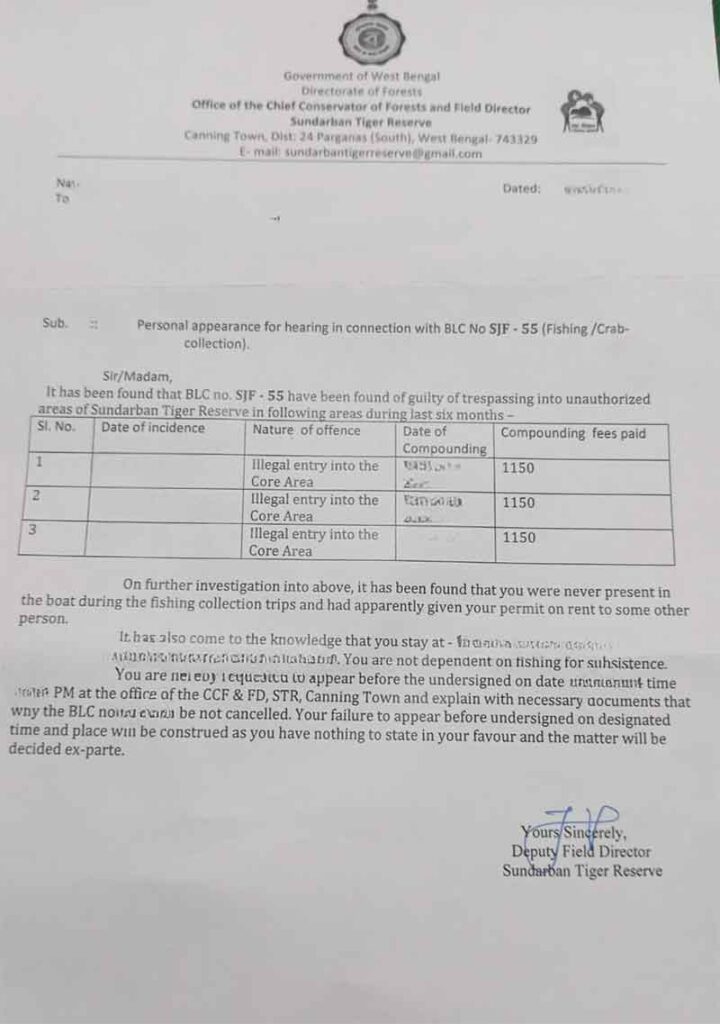

The fishers have to pay a hefty fine if they enter the purportedly ‘prohibited’ core area of the STR. the fine amounts payable by the fishers on such entry into the core area have continued to get steeper. During the fishing season of 2023, the fine amount payable on first such instance of entry into the core area of the STR was Rs. 750. In the current season, the forest department has suddenly raised it to Rs. 1150, without any prior intimation to the fishing community.

Notice Issued by Dy. F.D. STR revealing rising fine amounts within the same fishing season of 2023, i.e., the immediately last fishing season. Addressee details removed for privacy. As it happens, this notice was posted to the addressee by the STR after the date of hearing mentioned in it

A Notice reflecting rising fines payable by the STR fishers in 2024, Addressee details removed for privacy.

Armed forest personnel connected to the local beat and Range offices regularly seize without receipt and destroy the boats, fishing gears, nets, fish and crabs, firewood, and even much needed food and fresh water in possession of the fishing teams – all under the pretext of blaming the fishers for their entry into the forest areas. Beatings and detentions are not uncommon. Fearing the onslaught of such brutality, many fishing boats try to enter narrow creeks with forest-cover on both sides to hide from the forest department’s patrol boats, thus exposing themselves to wildlife attack.

Tiger attack claims the lives of more than 30 traditional fishers in the Indian Sundarbans every year. During the years of the Covid 19 pandemic-induced lockdown, the number was higher – as conversations with the local people of Sundarbans indicate. Fear of the brutalities perpetrated by the forest authorities on the local fishers based on legally unsubstantiable allegations of so-called “illegal entry” leads to under-reportage of such incidents.

Nearly every fisher of the Sunderbans have lost one or more of their family members, friends, neighbours and fellow-community members to tiger or crocodile attacks while pursuing their livelihood. This is a source of severe health stress, including psychological issues, for nearly all of them. Since the colonial times till date, the forest and other state-authorities have continued with the saga of systemic and systematic denial of their relief, recompense and welfare.

Ever since the inception of the colonial forest department till date, there is no record of the forest authorities having ever consulted or even given prior intimation to the affected people before declaring such ‘prohibited’ areas. Obtaining their free and informed consent prior and settling their livelihood and tenurial rights prior to imposition of such prohibitions, despite being legal duties of the forest department, continue to be honoured in breach.

Ironically, the STR, when it was born as a part of the central government-backed Project Tiger via a Government Order, dated 23 December 1973, was not a legal entity. It was not based on any of the then-extant forest laws. It found its legal backing through the 2007-amendment of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972, by which the concept of critical wildlife habitats was introduced in Indian wildlife conservancy law and the STR was notified as critical tiger habitat under the same.

Even the demarcation of the core and the buffer areas had been done, as it continues to be done in a completely arbitrary manner, without providing any rational substantiation or consultation with the local forest dependent peoples. Since the colonial times till date, through a series of departmental notifications the forest authorities have continued with the ‘tradition’ of reducing the geographic expanse available for the fishers to legally pursue their livelihood in the Sundarbans, without any prior intimation, consultation or consent.

This current year has already witnessed three ‘key developments’ which has increased the institutional exploitation of the small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans so much that more than 1 lakh fishers who and whose family-members depend on the Sundarban forests for their livelihood and sustenance find themselves at the brink of eviction today. Let us look at these one by one:

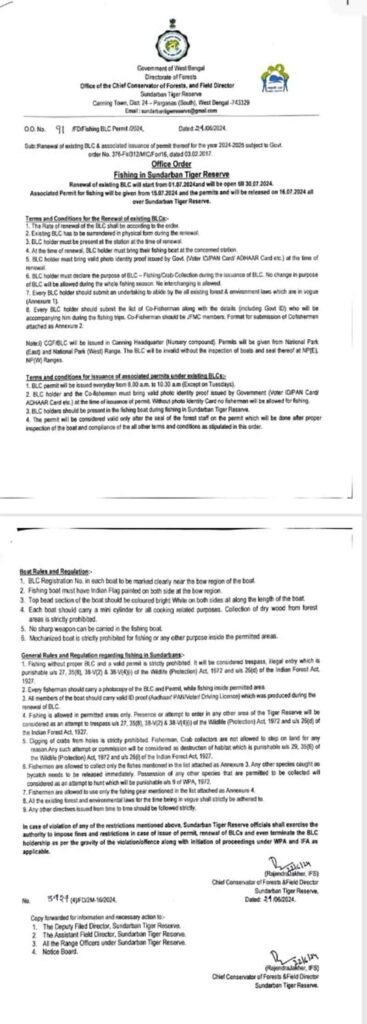

1. Office Order dated 24.06.2024 passed by the Field Director (FD) of the STR. This imposes several severe restrictions on traditional fishing activities. It seeks to establish a position that not only BLC-holders, but even the co-fishers, have to compulsorily be members of the Joint Forest Management Committee (JFMC)-s of villages within 1 km of the STR area. It is common knowledge that small scale fishers from villages much further away than 1 km from the STR sustain themselves through fishing in the Sundarban.

The reality, as it stands today, is that the forest department, in consultation with a Panchayat Samiti-s at the Block administrative level, determine 10-15 as JFMC-members of such villages. Even the local Panchayats have minimal involvement, leave alone legally mandated Gram Sabhas. Only the chosen JFMC-members get to participate in forestry and village-development activities, and reap all the benefits in the form of one-thirds the revenue collected by the forest department under the Minimum Support Price regime, along with additional lumpsums of Rs. 3-5 lakh given through the FD, STR to each such JFMC. The entire process is conducted in an extremely opaque manner, without any community-involvement. The beneficiaries, inevitably, have been people close to the ruling political parties, many of whom, especially the post-bearers, have ceased to go fishing in Sundarban in person to sustain their livelihoods.

It is not even so that all the STR-adjacent villages of the Sundarbans have functioning JFMCs. For example, at present there are only 27 villages in the Gosaba block which have active JFMC, and large section of their members do not regularly enter into the Sundarbans to collect fish, crab or honey for their subsistence-level livelihood. If one considers all the STR-adjacent blocks of West Bengal, there are only a handful few thousand people who are JFMC-members. When contrasted with the 1 lakh plus actual small-scale fishers of the Indian Sundarbans, this is a very small number – leaving the rest vulnerable to imminent eviction from livelihood.

In the Sundarbans, there is a government-enforced fishing ban-period in later summer and early monsoon. This is done to keep the fries and seedlings from getting destroyed. The new fishing season of a year begins in earnest from the beginning of July. This year, many boats, with the fishing teams riding the same, are not being allowed to enter even into the buffer area of the STR. The forest officials are insisting that the BLC-owners be present in person. The pretext being to end the BLC-renting system.

This, prima facie, is laudable. However, when seen in context in terms of these attempted enforcement of the office-order by the FD, STR dated 24.06.2024, certain discrepancies come to the fore. For instance, certain purported hearing-notices are being sent by the STR to some of the BLC-holders to appear on specified dates

Many BLC-holders, like Jahangir Molla from Canning, were not given notices. Whereas, for people like Haradhan Majhi Kultali, Rasidul Sheikh from Bally Satyanarayanpur, or Nripen Maity from Moukhali, all being BLC-holders, the STR authorities had posts them hearing notices on dates which are later than the hearing dates specified in these notices!

Meanwhile, Jaheda Bibi from Rajat Jubilee faces another problem. Her husband, Asadul, was a BLC-holder, but he had died in a tiger attack in 2015. It is indeed the case that even today, around 150-200 BLC-holders out of the 700 active BLCs operational in the STR area do indeed often go to fish in person. After her husband’s demise, Jaheda could procure a Nominee Certificate from the local Lahiripur Gram Panchayat, under which her village falls.

However, she is unaware of these new restrictions. She has even moved away from fishing and depends on livestock rearing. Since the past few years, she goes to work seasonally in the cloth mills of Bangalore. No one from her family knows what has happened to her deceased husband’s BLC, and neither does she.

The forest department has continued with taking various coercive measures against fishing teams, all under the pretext of enforcing this office order of 24.06.2024.

The fishers of the Sundarbans use a variety of traditional gears and methods to catch fish and crabs. These are not harmful to the environment, but, on the contrary, the conform to the principles of wise use. This year, such gears as fishing rods used for collecting crabs, various traditional nets of large or small knot-sizes, such as the Char-pata and Khal-pata nets, Chandi, Knata and Ber nets, even the wildly used Behundi or Beundi nets, and even instruments like knives, cutlasses and fishing knives which are essential in the traditional processes of small-scale fishing in the Sundarbans – are being seized by the forest personnel from the various range offices at the points of forest entry.

Initially, the forest officials were reluctant to share any list of ‘allowed’ nets. However, after a month of continued protests by the fishers at the STR and at the various relevant Range, Beat and National Park offices, an incomplete and unsubstantiated list was provided by the department, which excludes all these highly essential fishing-gear.

Likewise, the department has provided a list of 47 fish species which are allowed to be caught, without providing any rationale or substantiation. This list excludes more than 300 fish species which are regularly caught and sold by the Sundarban fishers. This is making a further dent on their economic security. No sustained attempts at conserving and enriching the fish resources of the Sundarbans with community participation were ever made, nor any unbiased carrying capacity study of the Sundarban waterways ever conducted.

The forest department, in effect allows fishing only in the buffer area of the Sundarbans. But no government department has made any effort to increase the fishstock in the flowing waterways of this area. The biodiversity and volume of available fish in the buffer area of the STR has severely depleted. This is because of activities like unmitigated tourism, commercial fishing by mechanised trawlers, fly-ash carriage, etc. This new office order dated 24.06.2024 issued by the FD, STR, in effect, makes this open and blatant mala fide position of the department ipso facto.

A list of the ‘allowed’ fishing nets given to the protesting fishers by the STR Office on the third week of July, 2024

In what makes this exploitative approach and mala fide intent clear, the fishers of the Sundarban are not being allowed to collect crabs from crabholes using fishing rods, and to collect even dead twigs and branches from the shorelines as firewood. Firewood stockpiled in the boats for use as fuel are being seized and destroyed by the forest department being They are being allowed to carry only one LPG cylinder for cooking, and not even a back-up – all in the name of enforcement of this order. The long wait to obtain clearance to enter the Sundarban forests during this ongoing season has led to essential life and livelihood-items like ice, salt and fresh, non-brackish water getting wasted.

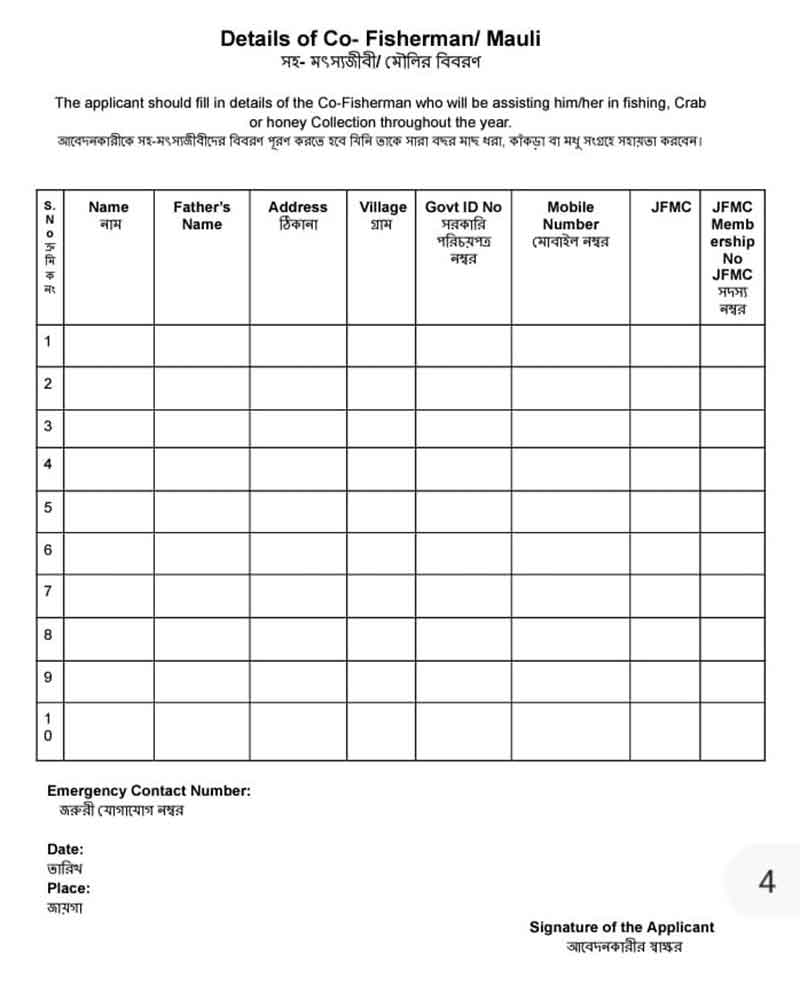

To add to the woes, even the BLC-holders who are being present before the forest offices prior to the fishing expeditions are being forced to write down the names of 10 co-fishers, whereas, in reality, around 3-4 co-fisher can have space in a dinghee-boats and can thus become a part of a fishing team. The remaining 6-7 co-fishers in such lists are not being allowed to take part in other fishing teams of other boats, and are thus facing imminent and ongoing unemployment.

Some BLC-holders are being coerced to write down names of 10 co-fishers in this list by the forest department, which also indicates at compulsory JFMC-ownership by the co-fishers

All in all, the STR office order of 24.06.2024 and its attempted enforcement has wreaked havoc on the livelihood security of many small-scale fishers of the Indian Sundarbans. It has led to a situation that more than 1 lakh fishers are finding it impossible to sustain their livelihood, and are thus being evicted from their livelihoods by the arbitrary actions of the forest department.

Meanwhile, forest entry through various waterways which have been traditionally and continually used by the small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans have been blocked by the forest authorities at various points such as Nabanki, Raimangal, Ganral, Chandkhali, Raimangal and Chhaya. This is forcing fishers from various villages in the Canning I and II, Mathurapur II, Jayanagar and even Hingalganj community developments blocks to take longer routes, moving through areas closer to the ocean-mouth of the estuary closer to the Sagar Islands.

Earlier on, during this ongoing fishing season of 2024, entry through the Kumirmari area of the Bagna Forest Range was also being blocked through placement of red signal at the point of forest entry. However, after sustained protests, the blockade has been lifted, and green signal has been obtained by the fishers to enter through that area.

Forest-entry of fishing boats through the Sajnekhali Wildife Sanctuary Range Offices has been allowed from the beginning of this season. However, it is the same said office which is offering to give temporary and seasonal BLC-s to the JFMC-members of some villages in the Gosaba and the Basanti administrative blocks, is collecting applications in lieu of Rs. 3,000 to Rs. 3,500 per application, from some of the JFMC-members in a very opaque way.

It is only because of the recent protests by some the fishers of the Sundarbans that this information has come to public knowledge. Though issuance of temporary and seasonal permits to all the real small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans is a laudable idea. However, issuance of the same only to the JFMC-members are bound to lead to massive exclusion for reasons discussed earlier.

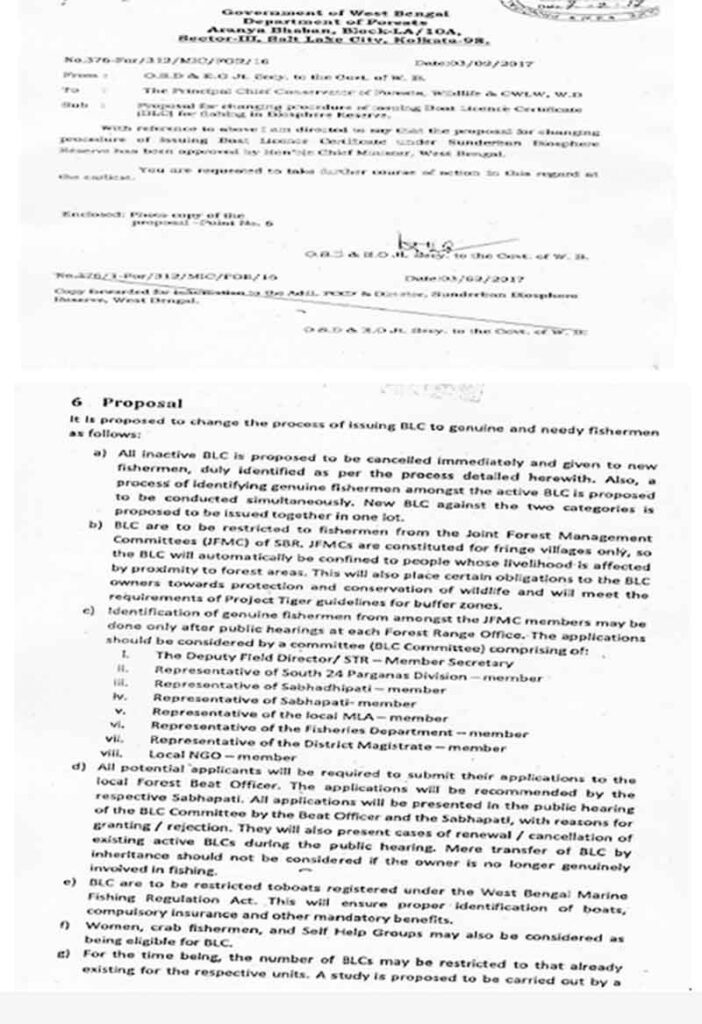

To add to the context, attempts made by the state to connect the BLC with the JFMC-membership is not new. It can be seen in a Proposal dated 03.02.207, approved by the Chief Minister of West Bengal and forwarded by the Joint Secretary to the Government of West Bengal to the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests and Chief Wildlife Warden of West Bengal. Thus, it can be seen that the attempted exclusion of the 1 to 1.5 lakh fishers of the Sundarbans from the scope of their livelihood is not a very new process. But it has surely received a shot in the arm by dint of the recent office order dated 24.06.2024 issued by the FD, STR.

The front page and a relevant page of the proposal dated 03.02.2017 of merging the JFMC and the BLC regimes, as approved by the Chief Minister of West Bengal

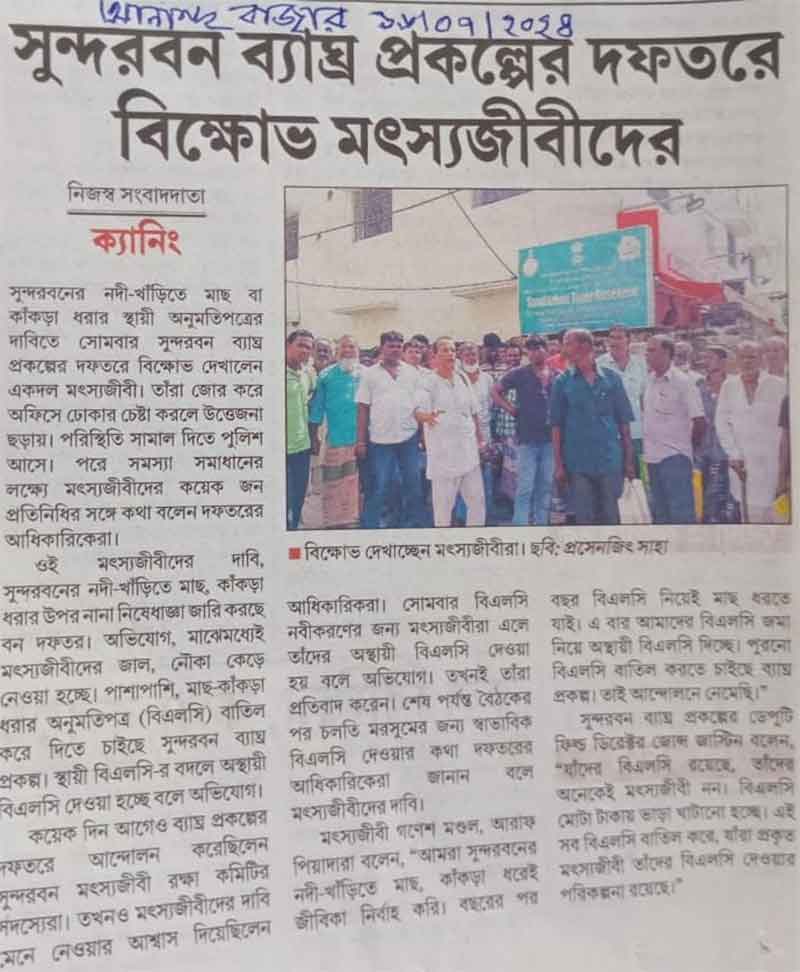

It is only through severe protests by some fishworkers from the Sundarbans made before the STR offices and before some of the Range Offices operating under it during June-July 2024 that the attempts at enforcement of mandatory JFMC-membership of all fishers – including of the BLC-holders and of all the co-fishers – as were made earlier on by the forest department, could temporarily be thwarted for this current and ongoing fishing season. Recent vernacular media reports of some instances of the ongoing protests by fishers from the Sundarbans against the STR-issued office order dated 24.06.2024 here, here, here, here and here.

A media report on the current and ongoing Sundarban fishers’ protests at the STR Office, Canning, against the STR-issued fishing order and its enforcement, published in the Anandabazar Patrika on 16.07.24

To add to the absurdity of the situation, the fishers who are attempting to obtain clearances for entry into the buffer area of the STR for carrying out their traditional livelihood are, during the current and ongoing fishing season, being told to paint a white line along the hull of the boat. There have been reports among the Sundarban fisher community of fishing boats being prevented from going into the flowing waterways of the forests owing to absence of such white lines along their hulls.

There is already a requirement of painting an orange-coloured line on both sides of the hulls non-mechanised marine boats, and, even in the eyes of the law, including the West Bengal Marine Fishing Act, 1993 and the various rules issued under the same, boat registration of marine fishers is an issue under the purview of the state fisheries department. Traditional fishers who ply their non-mechanised dinghee-boats in the rivers, canals and other flowing waterways of estuarine Sundarban are considered as fishers in the marine sector.

A separate process of registration of fishers and their fishing boats is conducted in the Indian Sundarbans by the state fisheries department through the Assistant Director of Fisheries (Marine) of the coastal South 24 Parganas district with offices at Diamond Harbour – all the way down to the Block administrative level through the offices of the Fisheries Expansion Officers there.

These parallel and overlapping processes have led to a situation where, if a boat of a team of small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans ply with an orange line painted across both sides of its hull, they are vulnerable to be stopped with their gear and fish being seized by the forest authorities. On the other hand, if such a boat has a white line instead, then the fishers riding it are vulnerable to face similar or different impediments to their livelihood from naval or police authorities.

In this way, through the office order issued by the FD, STR, on 24.06.2024 and through ongoing attempts to enforce the same being undertaken by the forest authorities throughout various regions the Sundarbans, the fishers are being unreasonably saddled with further vulnerabilities.

A copy of the office order issued by the FD, STR on 24.06.2024 that severly restricts the scope of livelihood of the Sundarban fishers

2. NTCA Nod to Expansion of the STR buffer area:

A recent newspaper report informs that, based on an earlier proposal by the West Bengal government, a technical committee of the central National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) has given the go-ahead for expansion of the buffer area of the STR through expansion of area in the Raidighi, Matla and Ramganga forest ranges of South 24 Parganas by 1,100sqkm.

No specifics of such expansion have been provided by the forest department in the public domain or to the local forest-dependent traditional and small-scale fishers. No efforts to inform them have been made, nor any free and prior informed consent taken from them prior to initiating such expansion.

Expansion of STR area is bound to bring sets of prohibitions imposed on their livelihood. Their rights to livelihood have, as has been discussed earlier, not been settled anywhere in the Sundarbans. Thousands of such fishers from the Diamond Harbour, Kakdwip and Canning subdivisions stand to have their livelihoods affected as a result of this proposed and possibly imminent expansion.

3. Attempts at changing the CZMP Map of South 24 Parganas

As discussed above, fishing in the waterways of the Sundarbans is considered as under the marine fishing sector. The tidal waterways of the Sundarbans, including the waterways within the STR, are considered as marine coastal areas and governed under the coastal regulatory regime – currently in force through the Coastal Regulation Zone Notification, 2019.

This law currently deigns to regulate various activities that directly involve or affect fishing, and envisages community participation at some levels. However, no such steps have till date been seen by the authorities to facilitate the participation of fishers in the democratic processes of law-implementation within the notified CRZ-areas, i.e., within up to 500 m from the High Tide Lines of the Sundarban rivers, streams and other flowing estuarine waterbodies.

At the same time, the CRZ Notification, 2019, seeks to regulate and not disallow traditional fishing activities from estuarine areas such as the deltaic Sundarbans on India, which constitute barely one thirds of the total Sundarban area spread across West Bengal and Bangladesh.

Nevertheless, this notification imposes some steep prohibitions on fishing in the name of mangrove conservation, while other destructive activities like the laying of pipelines, transmission lines, conveyance systems or mechanisms and construction of stilt roads have been specifically permitted even in “mangrove buffer” areas within the CRZ. The CRZ Notification 2019 was passed despite protests from fishworkers’ organisations from multiple places in India. Even this otherwise problematic notification imposes a legal duty on the relevant state authorities to organise public consultations while preparing maps and plans for the coastlines and coastal communities.

Against this backdrop, and in total breach of the legal duty of the state, the state of West Bengal has sought to alter the CRZ Maps for both the coastal districts of West Bengal – being South 24 Parganas and Purba Medinipur. As mentioned above, the CRZ area of the Sundarbans constitute a part of the coastline of the South 24 Parganas district. While attempting to change the Coastal Zone Management Plan (CZMP) Map of the South 24 Parganas, the West Bengal State Coastal Zone Management Authority (WBSCZMA), has been observed to have called for a public hearing in Office of the Additional District Magistrate and District Land & Land Reforms Officer, South 24 Parganas, at Alipore, Kolkata – more than 100 kms away from most of the coastal area of this district – on August 5, 2024.

This so-called ‘public hearing’ has been called for in an extremely opaque manner. No intimation about the same has been made in the public domain by the government. Nor have any notices been put up or awareness on the same done at the areas affected by such alteration of maps. A short notice, titled “Public Hearing Notice” in the name of the Member Secretary of the seem to have appeared in an English language newspaper calling for such a meeting on August 5 at the abovementioned office in Kolkata, but the same could not be traced further.

A legally unsound and dubious ‘Public Hearing Notice’ published in an English-language newspaper on the alteration CZMP maps of the S. 24 Parganas district by the WBCZMA

As per the legal mandate of the CRZ Notification, 2019, such public hearings require to be conducted at the affected areas, so as to ensure community participation. Clearly, the WBSCZMA authorities have not adhered to the law in this regard. In this way, the state is seeking to make vital alterations on its maps involving the CRZ area, and the same is being done behind the back of the communities small-scale coastal and estuarine fishers of south Bengal. This is despite the fact such alterations, if implemented, will have far reaching impacts on their traditional livelihood.

Thus, as we can see from the above discussion, the state of West Bengal has largely failed to perform their legal duties towards the communities of small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans. Instead, it has continued to deny them the settlement of their right to forest-dependent livelihood. Through its actions and inactions, the state, primarily through the forest department, has severely endangered the traditional livelihood of the small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans. The traditional and customary fishing practices in the estuarine waterways of the Sundarbans are not harmful to the environment. Rather, such generational practices are based on the sanguine principle of wise use.

Nonetheless, the bogey of mangrove destruction or tiger poaching – despite the former accusation being unsubstantiable as utterly incorrect and no instances of the latter having been observed to occur in the Sundarbans in the last 35 years – continue to be used in the mainstream, by the forest and other authorities, and even by international agencies – as a tacit justification of the denial of the forest dependent peoples of the Sundarbans their rights to pursue their traditional livelihood. The additional bogey of “illegal encroachment” in purportedly prohibited forest areas continue to further increase the vulnerabilities of a few lakhs of small-scale fishers from south Bengal.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

There is no denying that mangrove and tiger are important parts of the Sundarban ecosystem as it exists today, and need to be conserved. There is also no denying that the fish stock of the buffer area of the STR has reduced. However, subsistence level marine fishing activities done by the small-scale fishers of the Sundarbans cannot be blamed for this logically or in light of the reality prevalent in the Sundarbans in this regard. As has been discussed earlier, factors like unchecked tourism activities, rampant commercial, large-scale and destructive fishing activities conducted through mechanised trawlers, fly-ash carriage on large dilapidated marine vehicle along the vulnerable waterways, and the continued unwillingness of the forest and fisheries departments of the state to take any steps aimed at increasing the fish stock or preserving the bio-diversity of the fish species in the Indian Sundarbans are to blame for this.

Currently, the state authorities and even international agencies are observed to be espousing the causes of preservation of the vulnerable mangrove ecosystems and tiger conservation as pretexts to evict more than 1 lakh small-scale fishers of the Indian Sundarbans from their livelihood. No sincere efforts to account for and redress their vulnerabilities or to ensure their participation in the conservation of the ecologies which they depend on to subsist through generational livelihood-practices are being undertaken by the powers that be – at the grave expense of democracy in the Sundarbans.

Please stand in widespread solidarity with the small-scale fishers of Sundarban who face massive eviction today.

…

Atindriya Chakrabarty is a lawyer and legal aid worker who is currently working with the small-scale fishers and human-wildlife conflict (HWC)-impacted families in the Indian Sundarbans. This work is based on his experiences as the same. Many of the information in this work have been collected through interactions with various people from some parts of the Sundarbans, whom he has met in the course of his engagements with the Sundarban Byaghrobidhaba Samiti, a community based voluntary organisation of HWC-impacted families, and the Dakshinbanga Matsyajibi Forum, a trade union of small-scale fishers. The exact names and other specific details of the persons from the Sundarbans mentioned in this write-up have been altered for their privacy and security.