Recent remarks by the newly elected President of Iran have reignited the discussion about relocating the capital from Tehran. Massoud Pezeshkian has stated that, due to issues such as water scarcity, land subsidence, and pollution, there appears to be no alternative but to move the political and economic center of the country. This talk has generated some significant discussions and exchanges of opinions within Iran, especially by professionals such as city planners and architects, and other concerned individuals, Even outside Iran, mainly among diaspora, there has been some attention paid to this subject. How serious, fact-based and realistic this thought and proposal remains to be seen and tested.

This is not the first time that an Iranian president puts forward such an idea. During Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s administration, there was an attempt, if not just a talk, to decentralize Tehran by relocating some government offices and state-owned enterprises to provincial cities. However, the attempt proved unsuccessful and resulted in significant material costs and human resource losses.

In the first part of this article, I will provide some background and discussion of the experiences of similar attempts in other parts of the world, especially in countries with similarities to Iran. Further, I will make an attempt to put forward some lessons learned from those attempts. Finally, and in part two, I will discuss the pros and cons (positive and negative aspects) of a potential relocation of Tehran, the major metropolitan capital of Iran. Included in my discussion will be a perspective on how feasible and realistic the idea of relocation the capital of Iran maybe, even if there is real intention and not just pep talk about it.

Lessons to be Learned About New Capital Cities in a Global Context

The relocation of a capital city is a complex urban decision with various dimensions and consequences for both the old and new capital. It can be driven by political, economic, societal, and other factors. It certainly will urban and architectural implications for residents. The facts to consider with significant human and socio-economic-political impacts include, but are not limited to, climatic conditions, location finding, planning, design, budgeting of the new city/capital and re-purposing the old capital, its infrastructure and resources, and proper planning and implementation of the separation of the political and administrative hubs from cultural and economic functions in both cities.

To give discussion a more empirical perspective the experiences of some countries, similar to or not way different from Iran may be of importance. In this respect countries such as Egypt, Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) are chosen here. In light of the ongoing urban discourse, countries like Egypt are or have been constructing a new capital city to alleviate population and urban stress on their old capitals. Replacement of Cairo as the capital of the ancient country. Similarly, Indonesia has been planning a new capital in response to challenges faced by Jakarta, such as pollution, traffic congestion, and rising sea levels. Other countries on the global scene have relocated their capital cities, with valuable lessons to be learned from their experiences.

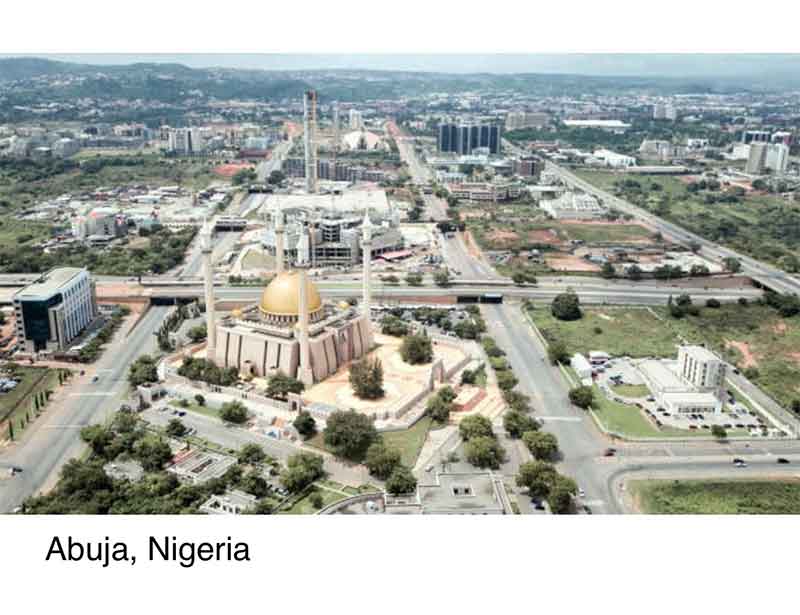

Brasilia, Brazil, is a well-known purpose-built capital city. It was established in the 1950s with the aim of relocating the capital from Rio de Janeiro to a location closer to the geographic center of the country. Similarly, Abuja, the capital city of Nigeria, was moved from Lagos in 1991 for similar reasons, such as overpopulation and Lagos being a cultural and economic hub where administrative functions struggled to thrive. Another example is Yamoussoukro, the purpose-built capital city of Côte d’Ivoire, which was founded in 1983 to replace Abjian as the economic capital.

These capital cities raise questions about the role of a city as an economic, cultural, or political and administrative centers. They highlight how a singular and top-down approach can influence the outcome of new cities and raise questions about the types of infrastructure, city planning and even architecture that are suitable for a purely administrative city. This article explores these concepts by examining and comparing the actions and responses of these three capital cities.

Top- Down Approach and Implementation or Natural and Adaptive Growth

New capital cities were created based on a rational and comprehensive model, emphasizing grand plans. Experts implemented top-down approaches to planning, aiming to break with tradition and initiate social change. The city’s character was determined by designers and planners, rather than evolving organically over time. This often resulted in a disconnect between the city and its residents due to the scale of the projects.

Brasilia and Abuja serve as examples of cities designed for car owners, with limited attention given to public transport, especially for those with limited budgets. The car-centric design leads to high vehicle dependency among the urban population, marginalizing pedestrians, and excluding social groups such as the poor and disabled. It also hinders the feasibility of future plans for effective communal transportation.

Urban Decadence or Dilapidated Neighborhoods

When cities lose their capital status, many administrative and political functions relocate to the new capital, leaving the physical structures that once housed them vacant or significantly under-utilized. Unfortunately, the aftermath of these relocations is often poorly planned for, resulting in abandoned buildings. Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil, is a prime example of such unfortunate outcome. The administrative buildings became obsolete when Brasilia became the capital city. However, as the homeless population in Rio de Janeiro has grown, organized squatting projects have emerged in an effort to repurpose these abandoned buildings as homes for the poor. Through established policies, squatters are granted a legal right to remain after five years, although establishing this right in practice is challenging.

In the case of Lagos, the former capital of Nigeria, there are numerous abandoned buildings as a consequence of the city losing its capital status. Within the Central Business District (CBD), there are approximately 60 structures ranging from 5 to 20 floors in height. However, the government has neglected these buildings and prevents squatters from permanently utilizing these spaces. This situation has resulted in an urban fabric filled with unused architecture.

Urban Developmental Imbalances

New capital cities often prioritize the design of governmental buildings, monumental structures, and landmark buildings to showcase power and praise society. This approach to city development creates grand structures that enhance the relationship between residents and the city’s elements. However, these ambitious developments, even if they are carried out by capable and resourceful and good-intentioned political establishments, must consider the economic realities of their respective countries. It is not uncommon for monumental architectural projects to be unsuitable for the economic climate of these countries. A prime example is Yamoussoukro, where many proposed massive developments were left incomplete due to an uncertain economic crisis. As a result, the city now consists of sparse land with only a few grand architectural structures.

It cannot be over-stated and over-emphasized that the urban planning and architectural schemes must adjust their expectations of modern construction to align with the economic realities of their contexts. This includes structuring designs that accommodate uncertainty while still striving for iconic aspirations. By incorporating incremental design strategies, commonly used in the development of social housing, into the construction of iconic buildings, a more sustainable and feasible approach can be achieved.

Natural Resources Losses

Brazil is well-known for its large and expansive forestry. However, in the case of Brasilia, 73% of the existing urban fabric was destroyed during the establishment of the new capital. This destruction included government buildings, residential and commercial areas, transportation infrastructure, and other necessary developments. Unfortunately, the design of these buildings and infrastructure did not make an effort to replace the vast forestry that was lost, resulting in a negative impact on the climate.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Learning from the consequences of deforestation in Brasilia, authorities i.n the development of Indonesia’s new capital city have ensured that the majority of land planned for urbanization consists of cultivated eucalyptus plantations rather than virgin rainforests. However, environmental groups have expressed concerns about the outcome, and demanded the release of environmental impact assessments before further development takes place.

It is sincerely, and whole heartedly hoped that if the capital of Iran is ever – in reality and not just talk — to be relocated from Tehran, the real, empirical examples of other such relocations, in the similar contexts be seriously, and sufficiently, studied, the consequences – originally expected, or unexpected – considered, and the lessons learned by taken into account. Otherwise, the results will be disastrous. Nobody should have any doubt about it.

To be continued in Part Two.…

Note:

This article has benefitted greatly from “Lessons from Relocating and Building New Capital Cities in the Global South” – Arch Daily, February 1, 2024

Additional information on this subject may be gained from the following sources

“Capital Cities: Varieties and Patterns of Development and Relocation” – Research Gate,

January 1, 2016

“New capital cities as tools of development and national development” – Science Direct

Sep 1, 2021

“Building New Capital Cities in Africa: Lessons for New Satellite Towns in Developing Countries” – Research Gate, September 26, 2017

Nov 9, 2023

Ali A Kiafar, PhD, REFP is a US-based City planner, researcher and academic