During my recent visit to the UK in August 2024, I was intrigued by the presence of imposing Church (Kirk) buildings in deteriorating conditions. In all cities and all along the way from London to Edinburgh by road or by train, church buildings are formidable and attractive. However, the buildings give the impression that those are not being used for congregational purposes. It was also obvious that no efforts are being made for their upkeep.

What do dilapidated church buildings in the UK indicate? It raises questions at three broad levels: one, the acceptance or non-acceptance of Christianity as a religion by the people of the UK; two, whether or not the values, mores, and ethics that guide inter-personal and societal relationships in the UK are guided by Christian theological perspectives; and three, how have the above two affected the institutional or structural relationship between the Church and the State in the UK? These are issues on which definitive statements should not be made without deeper objective examination. The ideas expressed here are based on recent visits to different parts of the contemporary United Kingdom.

People’s Detachment from Church Congregations

In Leads, Yorkshire, we have seen a church being used by the Sikh community as a Gurudwara. A huge, imposing church in Newcastle is more a tourist spot than a place of worship. The pews in the nave of the church have all been removed. However, the church has an eatery where tourists take rest and enjoy their food. The Oxford Church, which paved the way for the formation of Oxfam in 1942 as the Oxford Committee for Famine Relief, is more of a place of tourist attraction.[1] Vaults & Garden Café on the High Street, in Old Congregation House at St Mary’s Church in Oxford, is where I had a meeting with a friend. I had a sumptuous dinner with drinks in a church converted into a Slanj restaurant at Tarbet, Arrochar, near Edinburgh, Scotland. [2]

Church converted to a Gurudwara in Leeds

Church converted as Restaurant in Tarbet, Edinburgh

The ubiquitous presence of buildings and architecture that resemble designs of churches conveys eloquently the dominance of Christianity in defining the spatial perceptions of the residents of the United Kingdom. Churches are built by the communities. The disinclination of the communities to invest their time, money, and energies in the reconstruction or maintenance of the church buildings indicates those communities are moving away from the Christian religious teachings and the supremacy of the organized Christian churches in the UK—the Anglican, Presbyterian, and Catholic.

The decline of Christianity in the UK is not a tourist’s cursory observation. It is an issue being discussed in the UK. Neil John O’Brien, a Conservative Party Member of Parliament, titled his article, “The end of mainstream Christianity in Britain… And what will we do with all the churches?”[3] observes that the number of adults going to church on a Sunday is down about 40% since 2003, from 802,000 to 477,000. He further laments that, running current trends forward a few years, it seems impossible for the Church of England to maintain about 16,000 churches with a congregation. Establishing the case further, the Church of England has a webpage ‘Closed church buildings available for disposal’ and lists 13 church buildings immediately available for ‘sale or lease for a suitable use’.[4] The webpage observes that around twenty church buildings are closed for worship each year. A BBC report quoted the Trustees of the Church of Scotland as saying that they will have to close hundreds of churches in the coming years.[5]

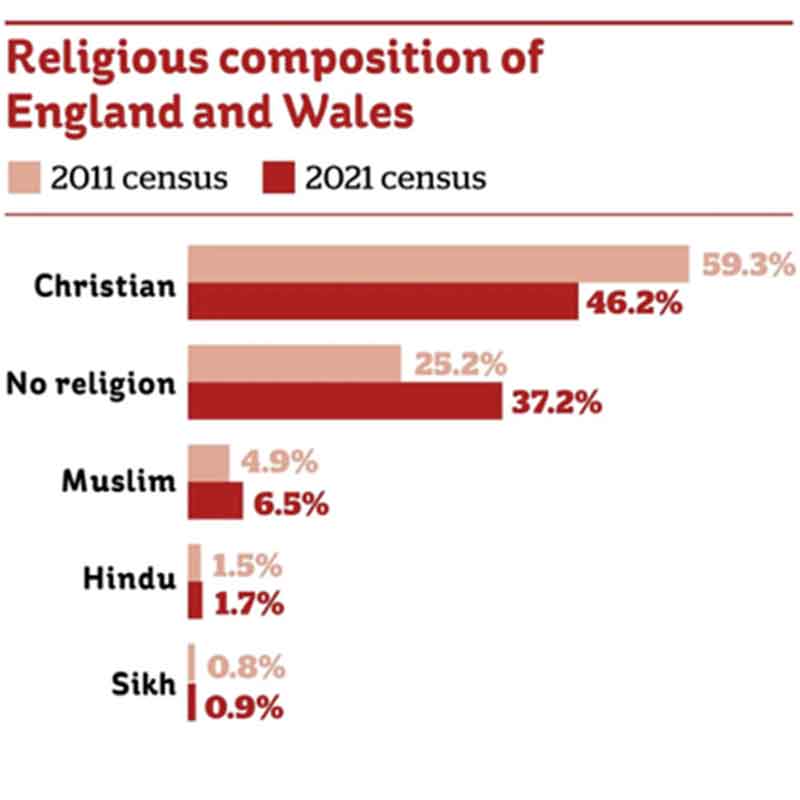

2021 UK Census[6] results substantiate the progressive alienation of the majority of the UK population from the Church. The census data suggests that Christianity is no longer the majority religion in England and Wales. Those who say that they are ‘Christian’ are down from 59.3 percent in 2011 to 46.2 percent in 2021. There has been an increase in other religions: Muslims increased from 4.9 percent in 2011 to 6.5 percent in 2021, Hindus from 1.5 percent to 1.7 percent, and Sikhs from 0.8 percent to 0.9 percent. In an article published in inews.co.uk, Katie Edwards,[7] an academic at the University of Sheffield, depicts the religious configuration of the population of England and Wales:

The Institute of Race Relations has examined Census 2021 data based on ethnicity.[8] The report says that in England and Wales, 81.7 percent of the population are white British. 9.3 percent are Asian (Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, other) groups; 4.0 percent are black groups; 0.7 percent are Chinese groups; 0.6 percent are Arab groups; and 1.6 percent are other groups. Katie Edwards observes that the proportion of those identifying as ‘non-religious’ increased from 25 percent in 2011 to 37 percent in 2021. This synchronises with the results of a survey conducted by the Bible Society, UK. When asked about their belief in ‘a God/gods or some higher power’, 38 percent said there definitely or probably was a God, while 49 percent said there definitely or probably was not.[9] Shedding the notions of Christian majoritarianism, along with the increasing federalism, the UK is also emerging as a multi-religious and multi-cultural country.

Census 2021 takes us to presume that a conspicuous number of British white people say that they are not Christians—they are non-religious. It also points out that those who immigrate to the UK prefer to adorn their religious identity, probably because religion is the most conspicuous element of community identity. Though information on the ethnic composition of Church membership in the UK is not available, based on data on immigration and membership between 2001 and 2010, a report of the Faith Survey has observed that Church membership has been significantly impacted by immigration.[10] Among the fastest-growing churches in the UK are Chinese[11] and African[12], both aiming to revitalize Christianity in the UK.

Church’s Diminishing Influence in Guiding Social and Interpersonal Relationships

Decreasing interest of mostly the white people of the UK in attending Sunday congregations of the Church, their reluctance to maintain Church buildings, and declaring that they are non-religious indicate declining capacity of the Church in influencing their interpersonal and social behavior. Christianity is conspicuously losing its agency as a civil religion in the UK. This takes us to the next important question: if not Christian theological perspectives defined by churches and their theological articulations, what else defines and guides the values, morality, and ethics for interpersonal and societal relationships in the UK? Can we say that secularism, rationality, and pluralism are providing alternative ethical fiber for the British communities? Let me venture into making a few cursory observations. The loss of Church as a point of assembly, where people come together and communicate, has been compensated by other venues in contemporary United Kingdom. Pubs, cafes, and restaurants are everywhere, which attracts people of all ages, sexes, races, or colors. There is no reason to assume that the relationships and communities created over here are discriminatory or beget violence. Everywhere in the UK, you are confronted with the reality of museums and hundreds of people thronging to visit the museums. The International Council of Museums gives this definition: “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets, and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible, and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally, and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection, and knowledge sharing.”[13] Museums are not places of worship; nobody places candles or flowers on any exhibit, and nobody prays or sings songs in front of any exhibit. Museums may convey a message—like many in the UK, which exalts the colonial past of British imperialism—but you are free to be agitated and to create your own narrative. There are 2500 museums in the UK, and more than 100 million people visit the museums annually.[14] These are big numbers, and these might be contributing to the replacement of churches as places of congregation and the sources for moral and intellectual fibre.

Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, Scotland

Probably, gardens and parks available all over the UK are also providing non-religious secular points of assembly for people. Hundreds of thousands of people throng these gardens and celebrate companionship and space. Unlike in some countries like India, which also prides itself on the numerous festivals it holds, the UK festivals are not linked to Christianity or any religion. The references here are festivals outside the religious domain, like Christmas, Easter, or Lent. Festivals could be music, literary, film, artistic, or theatric. It has been recognized that festivals have assumed the character of an industry, and they contribute in multiple ways to the UK economy. In written evidence submitted by UK Music in 2020 to the UK Parliament, it claims that the music industry is worth £5.8 billion and they contribute £1.75 billion to the UK economy.[15] Besides its economic contribution, festivals provide unconventional space and time for people, which is secular and safe. Festivals are class, gender, and age-neutral. It also provides opportunities for people of all faiths, colors, and races to participate without exclusion. It strengthens community feeling and provides opportunities for social interactions. Festivals, it is said, have the potential to advocate diversity, equality, inclusion, and human rights. For instance, Edinburgh has its festivals in August every year. I was in Edinburgh in August 2024. The entire city was overflowing with people, walking along the pathways as individuals, in groups, as families, men and women, children, young and old, who certainly might have come to participate in the Edinburgh Festival. Most of those in the streets were white people, speaking different languages indicating that they are from different European countries, and Brown and Black interspersed. Restaurants and eateries were everywhere, but fully occupied. La Clique Cabaret and Variety (Circus, Comedy) that we visited on August 18, 2024 was professional, spectacular, stunning, and breathtaking.[16] At the same time, it challenged some of the societal mores. Artists, in least offensive and in creative ways, displayed frontal nudity by female and male artists. La Clique provided hedonistic opportunity and a sense of diversity and freedom.

La Clique Cabaret & Circus, Fringe Festival, Edinburgh

There were some civic norms practiced by everyone that did not come from theological prescriptions. In the UK, a ‘left side’ driving country, vehicles move fast, being confident that those coming from the left will not obstruct the right of way. Those coming from the left diligently stop and give those from the right to move past. Grandparents take care of their grandchildren at home and in gardens. In festivals, the elderly are seen with their children and grandchildren. Everyone respects the other, irrespective of gender, age, or color diversities, at the counters and while crossing the road. Most of the people read books while on train rather than using their mobile phones.

Is There a Corresponding Decline in Relationship Between Church and State in the UK?

This takes us to the third concern: has the institutional or structural relationship between the Church and the State in the UK withered out? Protestantism defined the national character of the UK. As David Armitage discusses in his book, ’The Ideological Origins of British Empire’,[17] “English Protestantism… provided Englishness, Britishness, and the British Empire with a common chronology and a history stretching from the English and Scottish Reformations, through the attempted religious unification of the Stuart monarchies during the seventeenth century, across the Anglo-Scottish Parliamentary Union of 1707, and on to the United Kingdom of Great Britain that sat at the heart of the expanding British empire-state of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.” (David Armitage, 2004), pp. 62. He further says that Britain and the British Empire could be defined as Protestant, commercial, maritime, and free (liberty).

The island nations of England, Scotland, and Ireland have been hotbeds of religious intolerance and violence between Catholics and Protestants, Anglicans and Presbyterians, etc. since Henry VIII formed the Church of England, revolting against the authority of the Pope. Different factions of the church demanded voluntary or coerced conversion accompanied by extreme violence used by militant zealots on both sides to do away with heresy and silence dissent.[18]

Act of Union in 1707 linking Scotland to England and Wales as the United Kingdom of Great Britain had Protestantism as its ideological base.[19] In the other momentous developments in the 18th and 19th centuries in Great Britain, such as the anti-slavery movement that began in 1780 and led to the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the Reform Act of 1832, and the Emancipation Act of 1833, the Church was an active player invoking the principles of equality and justice as derived from Biblical teachings. The Chartist movement was a working-class movement that grew following the failure of the 1832 Reform Act to extend the vote beyond those owning property. Though it challenged the elitism of the established Church, bishops, and priests and its alliance with the state, it justified its core demands invoking Biblical sources.[20] In the 20th century, the UK Church supported and justified the ‘Welfare State’ status of the country. As Karl Mannheim said, “when religion was still alive and permeated society as a whole, both the conservative and the progressive forces developed their philosophies within the set framework of religion.”[21]

Today, the UK is a constitutional monarchy with the King as the head of the state and the Parliament having the power to make laws. Though the paramountcy of the legislature over the monarch diluted the identification of the church and the state, the monarch has to be “in communion with the Church of England,” and the sovereign holds the title “Defender of the Faith and Supreme Governor of the Church of England.” Twenty-six bishops from the Church of England, including the archbishops of Canterbury and York and the bishops of London, Durham, and Winchester, are in the House of Lords.[22] Despite this disinclination of the UK state and the Church of England to move away from their imperial alliance, neither of them could prevent the steady decline of the Church as an institution and the reality that Christian religiosity is no longer the defining characteristic of the identity of the people.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Conclusion

Rationality, secularism, and pluralism rather than religiosity appear to drive the ethical fiber of the citizens of contemporary Britain. This does not mean that Christianity as a religion stopped influencing the social and ethical character of the citizens of the UK. It will be too simplistic to argue that pubs, gardens, festivals, and museums are replacing churches as spaces of assembly and community bonding to provide the same purpose and meaning to individuals and to their social existence. The question is whether the purpose and meaning of life itself are transforming. Is this a dialectical process leading to a synthesis or a struggle where one necessary defeats the other? This requires further examination. Assimilating the given contexts of diminishing spacial influence as experienced in the dilapidated church buildings and increasing rejection of religious consciousness of the majority of its adherents, whether protestantism can transform itself is also something that calls for careful examination. A similar but serious question arises regarding the readiness and willingness of the state and the organized church in assimilating the complex reality of civil society and the evolving consciousness. One has to admit that the alliance between the organized church and the state continues. The implications of this for the state’s action in response to developments within and outside need to be constantly examined, considering its potential to influence civil society perspectives. The defining moments will be the state’s and church’s responses, internally, to the growing white supremacist militant movements, the existence of inter-religious rivalries and the counter demands for redefining UK nationalism within multicultural and multi-religious contexts, and, externally, to the war and killings in the name of religion.

[1] Oxfam International. (2024). Our history. https://www.oxfam.org/en/our-history

[2] SLANJ RESTAURANT. https://www.visitscotland.com/info/food-drink/slanj-restaurant-p2000331

[3] O’Brien, N. (2024). The end of mainstream Christianity in Britain. And what will we do with all the churches. https://www.neilobrien.co.uk/p/the-end-of-mainstream-christianity

[4] The Church of England. Closed church buildings available for disposal. https://www.churchofengland.org/resources/parish-reorganisation-and-church-property/closed-churches/closed-church-buildings

[5] Macaulay, J. (2023). Hundreds of churches will have to close, says Kirk. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-65645891

[6] Government UK. (2022). Population of England and Wales. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/population-of-england-and-wales/2.2/

[7] Edwards, K. (2022). Christianity in the UK is in decline but its influence is not – and that’s a real problem. https://inews.co.uk/opinion/christianity-in-the-uk-is-in-decline-but-its-influence-is-not-and-thats-a-real-problem-2000872?gad_source=1&gbraid=0AAAAABfPv1pcE7evumlQWHFLF0pwZrWfX&gclid=CjwKCAjwodC2BhAHEiwAE67hJN7AJxZoPUMTGR3P_Czj-RUh-bb_mC7Z4kLW1x6n7FAl2F5rtgDy_BoC930QAvD_BwE

[8] Institute of Race Relations. Ethnicity and religion statistics. https://irr.org.uk/research/statistics/ethnicity-and-religion/#:

[9] Lumino. (2018). More people don’t believe in God than do believe. https://www.biblesociety.org.uk/lumino/insights/national/more-people-dont-believe-in-god-than-do-believe/

[10] Faith Survey. (2013). Introduction: UK Christian Statistics 2: 2010-2020. https://faithsurvey.co.uk/download/csintro2.pdf

[11] Huang, Y. (2023). The fastest growing churches in the UK are…. Premier Christianity, October 23.

[12] Tomiwa Owolade 2023 Is the future of Christianity African? How immigration is revitalising British churches.

[13] International Council of Museums. (2022). Museum Definition. https://icom.museum/en/resources/standards-guidelines/museum-definition/

[14] Museums Association. How many museums are there in the UK? https://www.museumsassociation.org/about/faqs/#how-do-i-find-museums-in-the-uk

[15] UK Music. (2020). Written evidence submitted by UK Music.

[16] La Clique. (2024). LaClique: Cabaret, Circus, Comedy, Music. https://lacliquetheshow.com

[17] Armitage, D. (2004). The Ideological Origins of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press.

[18] Davidko, N. (2024). Violence in the History of England’s Christianity: A Study on the Basis of Religious and Literary Discourse. Athens Journal of History, 10(3), 213–250. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajhis.10-3-3

[19] Colley, L. (2003). BRITONS: Forging the Nation 1707-1837. PIMLICO.

[20] Faulkner, H. U. (1916). Chartism and the Churches: a Study in Democracy. AMS Press.

[21] Mannheim, K. (1943). Diagnosis of our Time: War time Essays of a Sociologist. Routledge.

[22] Torrance, D. (2023). The relationship between church and state in the United Kingdom. House of Commons Library.

J John is one of the founding editors of Labour File. He operates from Delhi, India