The eyes peer from a face lined with furrows. The locks of hair are white but despite her advanced age, she is an imposing figure. Bathed in limpid light she stands tall and erect on her land. The arresting image is that of Kong Spelity Lyngdoh Langein of Domiasiat, Meghalaya. Acclaimed photographer, documentarian, poet and activist Tarun Bhartiya, has chosen her as the scaffolding upon which to construct his project on refusals. As part of this project an exhibition of photographs, entitled “Em/No/ Nahi” will be held at the National Photography Festival 2025 organized by Navajivan Trust in Ahmedabad from January 2 to January 6, 2025.

Bhartiya, who has received acclaim for his films, has a varied body of work. These include: Brief Life of Insects (2015, Mumbai International Film Festival, Best Sound Award), The Last Train in Nepal (2014, BBC4) Royal Television Society award for Best Director, Factual), When the Hens Crow (2013) and Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (2010, Royal Television Society Award, Best documentary series).

He has also worked as editor on notable films with film-makers like Vasudha Joshi (Girl Song, Songlines and Cancer Katha, Special Jury Award, National Awards 2012), Red Ant Dream (Editor and Co-Writer, Sanjay Kak, 2014), Jashn-e-Azadi (Sanjay Kak 2007) and In Camera (Ranjan Palit 2010, National Award for Best Editing). He returned his Indian National Film Award in protest against the Indian government’s inaction against the attacks on minorities in India.

Says Bhartiya, “For a long time my partisanship used to embarrass me. The challenge is not so much in the making of the images – but the politics and history they have to carry. My struggle has always been that. I care about the aesthetics and technique but want not to get lost in that like some art photographer. That’s why I take so bloody long to think though the images, see their reception amongst the people, destabilise their ‘beauty.’

“I have till date never done any commissioned editorial work. Image-making for me, normally doesn’t start with big questions or ideas or events but as private curiosity… Wanting to know more, make friends, gossip or even participate in resistance movements…It’s mostly this.”

This reflection on refusal and the series of photographs capturing memories of resistance from the Khasi hills of Meghalaya spring from the decision of Spelity, 95, the matriarch of Domiasiat who simply said “No.” In 1993 she refused to lease her land to the Uranium Corporation of India Ltd (UCIL) despite being offered a sum of Rs 1.5 crore annually for thirty years.

She was considered not well- to-do, explained Bhartiya, but her resistance sprang from a very rich understanding of what freedom meant to her. Visiting her in her village, he had asked her about her decision, the amount of land she owned and other “sociological documentary” kind of evidence.

Amidst a clump of trees, behind which lay a hidden waterfall, she spoke about freedom. Money, she told him, could not buy the river, the land and the waterfall. Selling her land would be akin to selling her freedom.

A few months later during Bhartiya’s trip to Jadugoda, the region in Odisha which bore the scars of uranium mining, a UCIL official tried to counter the anti-uranium mining movement. He dismissed the displacement by claiming rehabilitation was possible and that some of the displaced would even get salaried employment. Development, he claimed, was freedom. People did not know the value of the land. He too spoke of freedom.

It is this notion of freedom which comes out of monetising ownership versus the freedom which comes out of belonging, that Bhartiya seeks to explore through 17 years of documenting struggles by people in the Khasi hills.

Spelity died in 2020 but backed by the Khasi Students Union, as an emblem of resistance, the people of the region protested and forced the state government in 2016 to revoke permission given to UCIL and its agents to mine uranium in Meghalaya.

Bhartiya also examines the refusal by people in the North East to engage with various modes of participation which the modern Indian state offers to indigenous people, living in lands on which lie rich resources. Tribal communities, have found that engagement with such institutions is heavily weighed against them.

Spelity, he says, refused to be killed by democratic dialogue. She just said “Em” (meaning no) (nahi) and became a talisman for her people. Em as a legacy is illustrated in the various struggles over the decades including the protest by the community against a dam to be constructed on the river Umngot.

Kong M, was just 10 when she joined protests in 2008. In 2021, Bhartiya documents how she hoisted her daughter on her back and told her “Remember Meeiid Spelity. We have to have her courage.” She proceeded with others singing songs about the river.

The deep sense of community and of belonging, the notion that land is not merely a factor of production but exists palpably in the imagination as an Eden to live in is manifested in Bhartiya’s images and some poems of the people.

In an evocative blend of the poetic and the political is the image of a Bah hillman under an expanse of open spaces framed against his jhum rice crop. Jhum is the traditional shifting cultivation farming technique practised in the North East.

In contrast is the image of brick-and-mortar construction in a pro mining village. A young girl is on an improvised swing made across a bamboo pole.

And there is then the image of a cement plaque recording the “donation” of the UICL in providing drinking water. An ironic comment on ownership of resources !

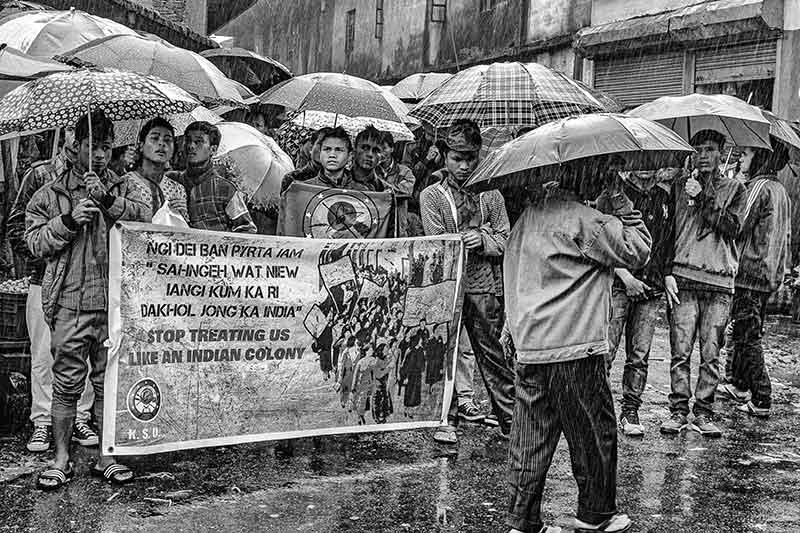

Then there is the protest portrait of a man in a traditional bamboo hat, smoking his pipe. But there is also the image of young men in modern attire, standing in pouring rain, under their umbrellas with the poster “Stop Treating us like an Indian colony. “Another image has the upraised hand of a woman saying no to a dam.” Does this suggest continuity, a unifying of people?

Making the most powerful of statements is “View from a police jeep.” A sea of posters and flags is in motion being held by the people. Each face is etched sharply as an individual but the message is collective.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

It is significant that the exhibition is organized by an institution established by MK Gandhi in 1919 to engage with the masses through his writings. The Navajivan trust continues to publish periodicals and books believed to be in the vein of Gandhian thought and is a well-established centre of intellectual and cultural activity in Ahmedabad.

Freny Manecksha is an independent journalist