The Quran, a vast ocean of guidance, establishes its own interpretive framework, declaring: “We have sent down to you the Book as clarification for all things and as guidance and mercy and good tidings for the Submitters” (16:89). This comprehensive mandate necessitates a nuanced hermeneutic, one that acts like a skilled navigator, distinguishing between the unchanging anchor of universal principles and the adaptable sails of contextual applications. This distinction is not merely academic; it is vital for Muslims navigating diverse cultural landscapes, particularly in India. Prophet Muhammad’s own practice exemplifies this when encountering Ethiopian cultural expressions: “Leave them alone, for indeed every nation has its Eid” (Bukhari 952). This wasn’t mere tolerance; it was an affirmation of legitimate cultural diversity operating within the broad parameters set by faith, recognizing that faith’s core message can be clothed in various cultural garments.

Distinguishing the Divine Blueprint from Cultural Scaffolding

The very language of the Quran provides crucial hermeneutical tools. It’s like examining the architect’s blueprints: verses concerning core worship (ibadat), the pillars of faith, predominantly use clear, imperative forms (amr). The command “Establish prayer” (2:43) leaves no room for cultural negotiation. Conversely, matters pertaining to social customs and daily life (adat) are often conveyed through descriptive narratives or permissive language. Descriptions of the Prophet’s meals or interactions, such as guidance on lawful food (“They ask you what is lawful to them. Say: ‘The good things are lawful to you'” – Quran 5:4), illustrate rather than rigidly prescribe specific cultural forms. This linguistic structure resonates deeply with the established jurisprudential principle, articulated by scholars like Ibn Qayyim: “The default position in customary matters (‘urf) is permissibility unless prohibited by explicit text (nass)”. This principle acts like an open field, vast and permissible, with prohibitions serving as clear fences around specific areas, rather than a narrow, prescribed path.

Historical precedents further illuminate this principle. When the Persian companion Salman al-Farisi proposed digging a defensive trench around Medina – a military tactic unknown to the Arabs but common in Persia – the Prophet readily approved. This decision underscored that beneficial practices and practical wisdom are judged by their utility and alignment with overarching Islamic objectives (maqasid al-Shari’ah), not by their geographical or cultural origins. Wisdom, in essence, is the believer’s lost camel, to be claimed wherever it is found.

Islam fundamentally emphasizes intention (niyyah) as the basis for the acceptability of actions. The true following of the Sunnah lies not merely in imitating the Prophet’s cultural habits but in embodying his character: his compassion, honesty, integrity, pursuit of justice, and wisdom. These are the timeless, universal values Islam seeks to cultivate.

Indian Muslims can be deeply devout while expressing their faith through the prism of their own cultural heritage. Praying in Arabic is essential for formal worship, but communicating, thinking, and creating in Tamil, Hindi, Bengali, or English is natural. Appreciating local aesthetics, literature (like the works of Kabir, Rahim, or Khusrau), and social customs, as long as they do not contradict core Islamic principles, enriches rather than diminishes one’s identity. Making Arab culture the qibla (direction of focus) instead of the truth of Islamic values misconstrues the Prophet’s mission, which was to elevate human conduct through integrity, not erase cultural identity through imitation.

The Arab Cultural Context: Universality and Particularity

The Quran, while revealed in 7th-century Arabia, is not a wholesale endorsement of Arab culture. It actively critiques detrimental pre-Islamic (Jahiliyyah) practices rooted in blind imitation: “And when it is said to them, ‘Follow what God has revealed,’ they say, ‘Rather, we will follow that upon which we found our fathers'” (2:170, 43:22). This rejection of uncritical traditionalism finds a parallel in the Prophet’s condemnation of tribalism (asabiyya): “He is not one of us who calls for partisanship or fights for partisanship” (Abu Dawud 5121). Faith was meant to transcend, not merely reinforce, parochial loyalties.

Yet, the Quran embraces linguistic particularity: “Indeed, We have sent it down as an Arabic Quran that you might understand” (12:2). This wasn’t to elevate Arab culture per se, but to ensure the message was initially clear and accessible to its first audience, acting as a chosen vessel for a universal cargo. The use of Arabic facilitated comprehension, establishing a principle that the divine message must be made understandable within any given context. This led jurists like the Maliki scholar al-Qarafi (d. 1285) to astutely observe in Al-Furuq: “The Sharia came to perfect noble character and facilitate human flourishing, not to mandate cultural uniformity across disparate lands.” It aims to polish the gem of human character, not necessarily recast its cultural setting.

Beyond Cultural Prescription

A central tenet derivable from the legal philosophy of the influential Maliki jurist Shihab al-Din Al-Qarafi (d. 1285 CE), particularly evident in works like Al-Furuq (Distinctions), is that the Islamic Sharia primarily aims to achieve higher ethical objectives and facilitate human well-being, rather than imposing specific cultural uniformity across diverse societies.

1. Emphasis on Maqaṣid al-Shariah (Objectives of Sharia): Al-Qarafi, like other major jurists, understood that the rulings of Sharia are not arbitrary but are designed to achieve specific, beneficial objectives. These objectives include the preservation and promotion of faith, life, intellect, lineage, property, and honour, as well as the cultivation of virtuous character. The ultimate goal is human flourishing in this life and the next.

2. Recognition and Validation of ʿUrf (Custom): A key aspect of Al-Qarafi’s methodology was his sophisticated treatment of custom. He recognized that many aspects of human interaction and social life are governed by local customs and norms. He argued that Sharia accommodates and even validates these customs as long as they do not contradict explicit scriptural prohibitions or fundamental Islamic principles.

3. Distinction between Universal Principles and Contextual Applications: Implicit in his validation of ʿurf is a distinction between the universal, unchanging principles and commands of the Sharia (e.g., core beliefs, pillars of worship, major ethical prohibitions like murder or theft) and the vast domain of permissible matters (mubaḥat) and social transactions (muamalat) where cultural context plays a significant role. The form these permissible matters take can vary widely according to local custom.

4. Implication of Non-Uniformity: By giving legal weight to varying local customs, Al-Qarafi’s approach inherently acknowledges and legitimizes a degree of cultural diversity within the Muslim world. If Sharia automatically invalidated all non-Arab customs, the concept of ʿurf as a source of legal consideration (in permissible matters) would be meaningless. His framework implies that Islam’s universal message can be lived out authentically within different cultural contexts.

5. Focus on Substance over Form: The overarching theme is that Sharia is more concerned with the ethical substance, underlying principles, and ultimate objectives (like justice, mercy, well-being, good character) than with rigidly prescribing specific cultural forms (like dress, architecture, or social etiquette, unless a specific textual command exists).

The statement, “The Sharia came to perfect noble character and facilitate human flourishing, not to mandate cultural uniformity across disparate lands,” serves as an accurate modern summary or encapsulation of these core ideas found within Al-Qarafi’s jurisprudence. It highlights his understanding that the Sharia possesses an inherent flexibility that allows it to take root and thrive in diverse cultural soils, focusing on cultivating the inner and outer well-being of individuals and communities according to universal ethical principles, while respecting non-contradictory local expressions of human culture.

Weaving Islam into India’s Fabric

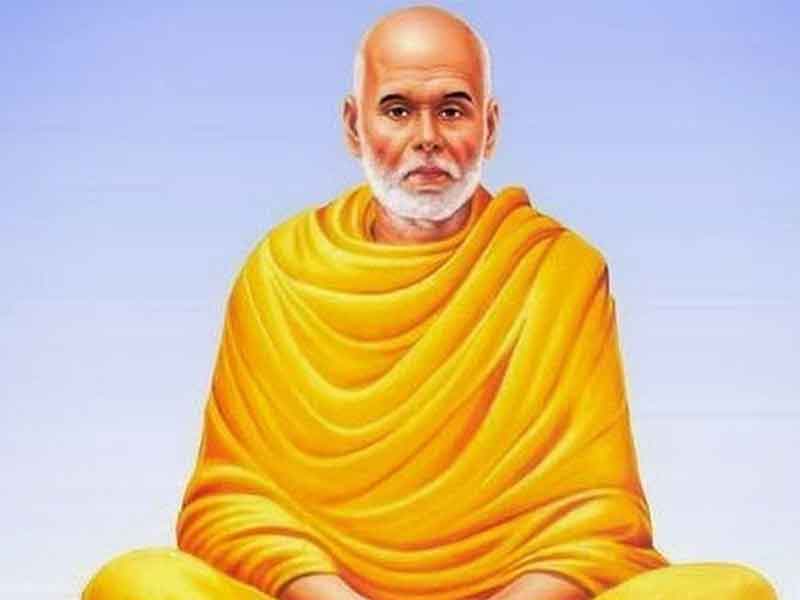

The Quran’s explicit celebration of diversity – “Among His Signs is the creation of the heavens and the earth, and the diversity of your languages and colours. Indeed, in that are signs for those of knowledge” (30:22) – provides the theological bedrock for culturally contextualized Islamic practice. This diversity is not accidental; it is presented as a sign of God’s creative power, a divine masterpiece painted on the canvas of humanity. Indian Muslim scholars, acutely aware of their unique milieu, built upon this foundation. Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (d. 1762), in his seminal Hujjat God al-Baligha, meticulously distinguished between “the essentials of religion (dharuriyyat), which are universal and unchanging, and its cultural manifestations (aadaab), which are contingent and adaptable.”

History bears witness to this dynamic synthesis, demonstrating the agency of Indian Muslims in weaving their faith into the rich tapestry of local culture:

1. Architecture: The iconic fusion in Mughal structures where indigenous elements like temple spires (shikhara) and decorative motifs blend seamlessly with Islamic domes and arches, creating a unique Indo-Islamic aesthetic.

2. Literature & Music: The genius of Amir Khusrau, who masterfully blended Sanskrit poetics and Indian musical traditions with Persian-Arabic literary forms, creating new genres like Qawwali and enriching Hindustani classical music.

3. Attire: The practical adaptation of local garments, such as the elegant dupatta evolving into a form of acceptable Islamic head covering (hijab) particularly in regions like the Deccan, demonstrating how modesty’s principle could find expression in indigenous styles.

Navigating Modern Life with Ancient Wisdom

Applying this Quranic hermeneutic – distinguishing the universal command from the specific cultural form – offers clear guidance for contemporary Indian Muslims:

1. Attire: The Quranic mandate is for modesty (“O Prophet, tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to draw their outer garments [jilbab] close around them” – 33:59). The core principle is covering and dignified appearance. The jilbab was a specific garment common in Arabia. Thus, an Indian sari, when worn consciously to fulfill the requirements of modest covering, serves the Quranic purpose as effectively as an Arab abaya. Modesty, therefore, has a diverse wardrobe.

2. Language: The Quran itself implicitly validates multilingualism in conveying faith (“And if We had made it a non-Arabic Quran, they would have said: ‘Why are its verses not explained in detail?'” – 41:44). The emphasis is on clarity and understanding. This validates the use of vernacular languages like Urdu, Bengali, Tamil, or Malayalam in sermons, religious education, and devotional expression. The 18th-century Fatwa-e-Alamgiri, compiled under Mughal patronage, explicitly permitted the use of local languages (like Urdu/Hindustani) in sermons (khutbahs), recognizing the need for comprehension. Different tongues can praise the One God.

3. Interfaith Relations: The Quran acknowledges righteous people among other faiths (e.g., 3:113-114) and the Prophet’s own life demonstrates positive interaction, such as accepting gifts from non-Muslim leaders and establishing treaties. The verse praising those who “give food, despite their love for it, to the poor, the orphan, and the captive” (76:8), often interpreted in the context of Ahl al-Bayt, sets a paradigm for compassion transcending religious lines. This allows Indian Muslims to participate meaningfully in India’s pluralistic society, sharing cultural celebrations (like exchanging greetings or sweets on festivals) and engaging in acts of mutual welfare, building bridges of goodwill without compromising core theological tenets.

Challenges to an Authentic Hermeneutics: Navigating Troubled Waters

Implementing this nuanced approach faces contemporary challenges that require careful navigation:

1. Arabization Movements: Fuelled often by petrodollar influence and simplistic interpretations, these movements tend to conflate the universal “Sunnah” (Prophetic tradition and underlying principles) with specific “Arabiyyah” (Arab cultural practices). This mistakes the cultural shell for the spiritual kernel, ignoring the Quran’s explicit celebration of diversity: “O mankind, indeed We have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may deeply know one another.” (49:13). The purpose of diversity, the verse implies, is mutual understanding, not cultural erasure.

2. Cultural Essentialism & Performative Religiosity: Reducing complex Islamic identity to easily identifiable, often imported, visual markers (specific dress styles, beards, etc.) contradicts the Prophet’s emphasis on inner piety: “Indeed, God does not look at your appearances or your wealth, but He looks at your hearts and your deeds” (Muslim 2564). Faith becomes an inner landscape nurtured by intention and action, not merely a set of outward signposts. This essentialism can alienate Muslims comfortable with their indigenous cultural expressions.

3. Historical Amnesia: A worrying trend involves neglecting or even denigrating India’s rich history of Islamic cultural synthesis and intellectual dialogue – from the syncretic explorations (however controversial) during Akbar’s era to Dara Shikoh’s profound attempt to find common ground in Majma-ul-Bahrain (“The Confluence of Two Seas”). Forgetting this legacy uproots the community from its historical soil, impoverishing contemporary discourse and making imported norms seem like the only “authentic” option.

A Proposed Hermeneutical Framework: A Compass for Cultural Navigation

To navigate these challenges, drawing upon classical usul al-fiqh (principles of jurisprudence) and addressing contemporary needs, this essay proposes a framework centered on:

1. The Five-Tiered Test of Cultural Practice (as a guide, not rigid dogma): Any cultural practice considered for adoption or continuation should ideally be assessed through this hermeneutical compass:

o Quranic Compliance: Does it explicitly contradict a clear prohibition (haram) in the Quran or established Sunnah? (Foundation)

o Alignment with Prophetic Intent: Does it align with the higher objectives (maqasid) of Sharia, such as justice, mercy, wisdom, and human welfare? (Direction)

o Cultural Continuity & Benefit: Does it preserve beneficial, non-contradictory local traditions (‘urf) that enrich community life? (Local Knowledge)

o Social Harmony: Does it foster peaceful coexistence and mutual respect (ihsan) within a pluralistic society? (Good Neighbourliness)

o Personal Conviction & Sincerity: Does it resonate with the individual’s sincere understanding and practice of faith (ikhlas)? (Inner Compass)

2. Guiding Principles of Contextualization (The Guiding Stars):

o Taysir (Facilitation): Drawing from “God intends for you ease and does not intend for you hardship” (2:185), favouring interpretations that make righteous practice accessible.

o ‘Urf (Custom): Recognizing the validity of local customs that do not contradict explicit texts, based on principles like “What Muslims collectively see as good is good in the sight of God” (attributed to Abdullah ibn Mas’ud, cited by Ahmad).

o Maslaha (Public Interest/Welfare): Prioritizing actions that secure genuine benefit and prevent harm for the individual and community, guided by principles like “The prevention of harm takes precedence over the acquisition of benefits.” (Kamali, p.190).

Toward an Authentic, Rooted Indian Muslim Identity

The Quran describes the Muslim ummah as “a middle community” (2:143)—one that harmonizes divine guidance with human wisdom, unwavering principle with adaptive expression. For Indian Muslims, this means confidently inhabiting the intersection of faith and culture, embodying the universal essence of Islam while allowing it to flourish through India’s civilizational idioms. Like a tree deeply rooted in Quranic soil yet branching into the Indian sky, their identity thrives when nourished by both revelation and heritage. The Prophet’s teaching—”Wisdom is the lost property of the believer” (Tirmidhi 2687)—invites Muslims to reclaim the profound wisdom embedded in their own land, traditions, and shared history.

This is not a dilution of faith but its fulfilment. Islam’s distinction between timeless principles (kulliyyat, as articulated by Andalusian jurist al-Shatibi) and transient cultural forms allows Indian Muslims to prioritize ethical substance over borrowed imitation. By centring Islam’s spiritual and moral universals—compassion, justice, sincerity—they transcend rigid cultural binaries, cultivating a piety that is both authentically Islamic and organically Indian. Such an approach mirrors Islam’s historical adaptability, fostering a lived faith that contributes to India’s pluralistic tapestry.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

In doing so, Indian Muslims become witnesses unto humanity (Quran 2:143), proving that true devotion lies not in performative uniformity but in embodying transcendent values within one’s own context. Their identity, like the Quranic ummah (community), is a bridge: rooted in divine truth, yet radiating through the beauty of India’s diversity.

Bibliography

Kamali, Mohammad Hashim, Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 2003, 383-386

Wood, Graeme, The ‘Caliph’ Speaks The Atlantic, November 4, 2016

V.A. Mohamad Ashrof is an independent Indian scholar specializing in Islamic humanism. With a deep commitment to advancing Quranic hermeneutics that prioritize human well-being, peace, and progress, his work aims to foster a just society, encourage critical thinking, and promote inclusive discourse and peaceful coexistence. He is dedicated to creating pathways for meaningful social change and intellectual growth through his scholarship. He can be reached at [email protected]