I was not born a Sufi Muslim. I was born, like most others, into a ready-made religion, handed down like an heirloom from generations before me. It came wrapped in customs and commandments, rituals and prohibitions. For a long time, I accepted all of it without resistance, without suspicion, without even understanding that there could be something to resist or suspect. It was the water I swam in, the air I breathed. To question it was as inconceivable as questioning the blue of the sky.

In those early years, religion to me was a matter of compliance. It was about knowing the right answers to the right questions. It was about belonging to the right group, defending the right ideas, performing the right actions at the right times. It was not about thinking; it was about repeating. It was not about searching; it was about safeguarding. I wore my faith like an armor, heavy and creaking, believing that every doubt was an enemy, every deviation a betrayal.

But somewhere along the way, a hairline crack appeared in that armor. I cannot remember the exact moment it happened — these things rarely announce themselves with fanfare. It was probably a slow, almost invisible erosion. A lingering dissatisfaction that prayers recited by rote could not soothe. A dull discomfort with the easy contempt I saw directed towards those who believed differently. A gnawing feeling that somewhere beneath the beautiful surface of my religion, something vital was missing.

And so began, almost against my will, the slow waking from what I now recognize as a kind of dogmatic slumber. It was not a sudden epiphany but a long, often painful process. Like muscles stiff from disuse learning to stretch again. Like eyes accustomed to darkness squinting in unfamiliar light. And the force that pulled me through that journey was what the world calls Sufism, though it would be more accurate to say it was the spirit of inquiry, compassion, and wonder that true Sufism embodies.

Sufism did not give me new answers as much as it gave me new questions. Questions that the rigid structures of my childhood faith had never encouraged. Why must God be imagined as a distant monarch rather than an intimate presence? Why must religious identity be a fortress rather than a bridge? Why must truth be a weapon rather than a light?

For the first time, it became permissible — even necessary — to ask these questions. And with every question asked, another idol crumbled. The idol of certainty. The idol of exclusivity. The idol of fear. Slowly, the contours of my faith began to shift. The edges softened. The walls thinned. The air became breathable again.

Sufism taught me that God is not a bureaucrat counting my mistakes, but a mystery too vast for my categories, too intimate for my rituals. It taught me that religious texts are not legal documents to be brandished, but love letters to be pondered, struggled with, wept over. It taught me that truth is not a monopoly owned by any single sect, but a vast ocean in which all sincere seekers swim, some nearer to the shore, some farther, but none in possession of the whole.

In liberating my mind from the grip of religious obscurantism, Sufism expanded my universe. It taught me that faith is not the opposite of reason but its companion. That doubt is not a sin but a stage of growth. That questioning is not rebellion but homage to the God who created my mind as well as my heart.

Before Sufism, I had believed — without ever consciously thinking it — that Islam was a small, closed system, a fenced garden with strict rules about who could enter and who must be kept out. After Sufism, I understood that true Islam is vast and open, not a fortress but a horizon. A horizon towards which I could walk my entire life and never exhaust its mystery.

Sufism also shattered my arrogant assumptions about other religions. I had been taught to view them with suspicion or pity, as systems fatally flawed, shadows compared to the full light of Islam. Sufism, however, whispered a different truth into my ear: that every genuine search for the divine, no matter the language or form, is worthy of respect. That God’s mercy is not confined to the borders we draw on our maps or in our minds. That beauty and wisdom are scattered like seeds across all cultures, all traditions.

This realization did not weaken my attachment to Islam; it deepened it. It made it richer, humbler, more grateful. I no longer needed to assert the superiority of my religion in order to feel secure in it. I could allow it to be itself without needing to belittle others. I could love it for what it is, not for how it could be weaponized in a competition.

Sufism taught me that humility is not an ornament worn for public display, but the only soil in which real faith can grow. That certainty is often the enemy of understanding. That to love God is also to love His creation, in all its wild diversity, in all its maddening complexity.

It also changed my relationship with God in profound ways. Before, God had been an external authority, demanding obedience, quick to punish, difficult to please. After Sufism, God became an inner presence, a companion on the road, a silence full of meaning. Prayer was no longer a performance but a homecoming. Rituals were no longer obligations but opportunities. Theology was no longer about proving points but about nurturing wonder.

Perhaps most importantly, Sufism taught me that liberation is not a destination but a journey. Mental freedom is not achieved once and for all, but must be fought for daily, against the gravitational pull of dogma, fear, and laziness. The mind longs for easy answers, the heart for simple loyalties. It is so much easier to outsource one’s conscience to an authority figure, to trade complexity for slogans, to swap thinking for allegiance.

Sufism reminds me, again and again, that this is not enough. That a faith unexamined is a faith unworthy of the God it claims to honor. That true submission to God requires first the courage to think freely, feel deeply, and live honestly.

Today, when I say I am a Muslim, I do so with a different spirit than before. Not as a badge of superiority, not as a barricade against the world, but as a confession of awe at the mystery of existence. As an ongoing conversation between my finite mind and the Infinite. As an allegiance to a way of being in the world that values mercy over judgment, curiosity over rigidity, love over fear.

I owe this transformation to Sufism. Not the Sufism of clichés and slogans, not the Sufism marketed as an exotic accessory for restless souls, but the Sufism that demands real work: the painful unlearning of inherited prejudices, the rigorous examination of one’s own motives, the relentless cultivation of compassion.

Sufism did not offer me escape from the hardships of religion; it offered me a deeper, harder, more beautiful challenge: to live a life of authenticity. To refuse easy answers. To remain vulnerable to wonder. To keep my heart broken enough to be open, and open enough to be broken.

It Is not an easy path. Some days, I long for the comfort of certainty, the security of belonging to a group that tells me exactly what to think and how to act. Some days, I grow weary of the loneliness that comes with refusing to fit neatly into any box. But then I remember: freedom was never supposed to be easy. It was only supposed to be true.

And so I remain — by choice, by necessity, by grace — a Sufi Muslim.

Because mental liberation, once tasted, is too precious to abandon.

Because wonder is too sacred to surrender.

Because love — and the freedom it demands — is the only way I know how to live.

But liberation, I realized, was not simply the absence of chains. It was the discovery of new muscles — muscles of thought, of discernment, of quiet courage — muscles that had long been allowed to atrophy under the weight of unquestioned tradition. Sufism did not merely ask me to dismantle the idols outside myself; it demanded the far harder task of dismantling the idols inside — the false certainties, the inherited prejudices, the need to be right rather than to be real.

There were days when this internal demolition felt exhilarating. I would feel the fresh air rush into rooms that had long been shut. I would marvel at how much larger the world looked once I stopped measuring it only by the coordinates I had been taught. There were other days when it felt like grief — a mourning for the comforting simplicities I could no longer return to, a homesickness for a home that had never truly existed. Nobody warns you how lonely freedom can be, how much heavier thinking is compared to believing.

When the scaffolding of dogma falls away, you are left exposed — to doubt, to ambiguity, to complexity. It is tempting to rebuild new scaffolding as quickly as possible, to find a new set of slogans to cling to. But Sufism taught me to resist that temptation. To sit, instead, in the uncomfortable spaces between answers. To cultivate the patience to live with questions that may never find perfect closure. To understand that mystery is not a failure of understanding, but a dimension of reality itself.

Through Sufism, I learned to honor the slow unfolding of insight, to recognize that real growth is often silent and subterranean, like seeds splitting open under the earth. I learned that faith deepened not despite doubt, but because of it. That the mind’s hunger for meaning is itself a form of devotion, an echo of the soul’s yearning for the infinite.

As my mind grew freer, so too did my heart. Tolerance was no longer a duty, a line to memorize about “respecting others” while secretly pitying or judging them. It became an instinct, a natural outgrowth of realizing how vast and uncontainable truth really is. It became impossible for me to dismiss other traditions as simply “wrong” or “misguided.” I could no longer see other seekers — whether Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, or atheist — as anything other than companions on the same immense, bewildering journey.

And once I saw that, the divisions that had once seemed so clear — believer and nonbeliever, pure and impure, saved and damned — began to blur. I saw devotion in a temple bell’s echo. I heard longing in the stillness of a church. I recognized a kind of prayer in the questions of an honest skeptic. The universe was no longer a battlefield between rival truths; it was a tapestry, woven from countless threads of yearning.

This shift did not come without cost. In the communities I had once called home, the price of such openness was suspicion. I learned that nothing is more threatening to a closed mind than an open one. I learned that questioning even the smallest dogma could provoke fierce resistance, not because people love falsehood, but because they fear what will happen to their world if the old certainties crumble. I understood, painfully, that religious communities often prize conformity over curiosity, loyalty over integrity.

At times, this estrangement cut deep. There is a particular kind of loneliness that comes from being seen as a heretic by the very people who once embraced you. There is a particular kind of ache that comes from speaking a language of openness to those who only recognize the dialect of certainty. And yet, Sufism gave me the courage to endure that loneliness, to trust that a faith worth having is a faith worth suffering for.

The more I allowed Sufism to reshape my soul, the more I understood that the real journey of faith is not about arriving at a final destination of right belief, but about remaining forever open to the unfolding mystery of God. It is about learning to love without needing to control. To seek without needing to possess. To kneel not out of fear, but out of awe.

I began to see religion itself differently. Not as a closed system of laws to be enforced, but as a living tradition, breathing and evolving with each generation. I saw that every great religious revival, every renewal of faith, was not a return to some imagined golden age, but a courageous act of reimagining. I saw that Islam, at its best, had always been dynamic, curious, intellectually adventurous — not the brittle, rule-obsessed caricature that so many had made it.

And with that realization came a deep sadness — a mourning for what had been lost in so much of contemporary religious life: the willingness to wonder, the openness to otherness, the humility before the sheer magnitude of the divine. But Sufism did not allow me to dwell too long in sadness. It pointed me instead towards gratitude — gratitude that such a path still existed, that the embers of the original fire still burned, however faintly.

I began to find traces of that fire in unexpected places — in the writings of mystics who spoke in the language of love rather than law, in the prayers of poets who questioned as boldly as they praised, in the silences between verses of the Quran when read not as a legal code but as a song of the soul. I found it in the conversations with strangers whose very difference taught me something new about the vastness of God.

Slowly, imperceptibly, my notion of worship expanded. It was no longer confined to ritual acts performed at prescribed times. Worship became a way of being in the world: attentive, grateful, wondering. It became an openness to beauty wherever it appeared — in the laughter of a child, in the symmetry of a leaf, in the fierce honesty of a doubter.

Prayer, too, changed. It was no longer a set of words recited on cue, but a kind of breathing. A way of tuning my heart to the deeper rhythms of existence. Sometimes it was wordless, a simple ache directed at the unknown. Sometimes it was messy, tangled with anger and confusion. Always, it was real.

In this way, Sufism did not abolish religion in my life; it transfigured it. It burned away the husk to reveal the kernel. It taught me that faith is not a set of propositions to be defended at all costs, but a living relationship — fragile, evolving, alive. It taught me that God is not a question to be answered, but a mystery to be lived.

The more I surrendered to this understanding, the less anxious I became about being “right.” I no longer felt the desperate need to win arguments or convert others. I realized that truth, if it is truly truth, does not need me to defend it like a cornered animal. It is like the sun: it shines by its own light, indifferent to my approval or my anxiety.

This realization brought an immense relief. It allowed me to listen, really listen, to those who thought differently. It allowed me to be wrong, to change my mind, to admit ignorance without shame. It allowed me to experience faith not as a possession but as a pilgrimage — a long, winding road towards a horizon that kept retreating the closer I drew to it, and yet whose very distance called me onward.

Even my relationship with religious texts changed. I no longer read them as manuals of behavior, full of hidden traps and technicalities. I read them as records of human longing for the divine, full of poetry and pathos and profound ambiguity. I learned to dwell in the spaces between the lines, to listen for the silences as well as the sounds. I learned that revelation is not a monologue but a dialogue, and that the divine speaks not only through words but through wonder.

And perhaps most crucially, I learned to forgive — myself, others, even the tradition that had once imprisoned me. I saw that those who cling to dogma are often themselves prisoners of fear, doing the best they can with the tools they have. I saw that certainty, while comforting, is a poor substitute for love. I saw that the work of liberation is not to mock the imprisoned, but to light torches along the path.

Today, when I look back on the person I was before Sufism, I do not feel disdain. I feel compassion. That version of me was not wicked, only wounded. Not malicious, only misled. I had inherited a system that taught fear more than love, rigidity more than curiosity. Escaping that system was not an act of rebellion against my faith, but an act of fidelity to its deepest spirit.

For Islam, at its heart, calls not for blind obedience but for conscious submission. Not for the closing of the mind but for its awakening. Not for hatred of the other, but for hospitality towards all. It was only through Sufism that I learned to see this. Only through Sufism that I learned to become, at long last, a Muslim in the truest sense: one who surrenders not out of fear, but out of love.

And so I continue on this path — stumbling, straying, sometimes despairing, but always returning. Always seeking. Always refusing to trade the messy beauty of freedom for the cold comfort of certainty.

Because to live otherwise would be to betray the liberation that Sufism gave me.

Because, in the end, freedom — real freedom, the freedom of the mind and the heart — is not a luxury.

It is a calling.

It is a duty.

It is the only way I know how to honor the mystery of being alive.

And so, as I continue to walk this path — one that grows increasingly uncertain and more luminous with every step — I realize that I have not “arrived” anywhere. I have simply begun to open my eyes to a wider, truer vision of the world. Sufism didn’t give me all the answers, nor did it promise that life would become easier or more predictable. It only promised a deeper awareness, a freedom to see the world with eyes that no longer flinch at the complexities or contradictions of existence.

I look at my old self sometimes, with its rigid beliefs and narrow views, and I feel a kind of gentle pity. Not for my past self, but for the way that fear and certainty can shape a soul into a tight knot. How easy it is to live in the shadow of unchallenged truths, to feel a false sense of security when we hide behind the walls of dogma.

But Sufism showed me that true security does not lie in the absence of questions, but in the embrace of them. It taught me that God is not found in the answers, but in the questions themselves — the longing, the yearning, the reaching towards something beyond what we can grasp. It revealed to me that the beauty of life is not in the certainty of our beliefs, but in the mystery that surrounds us and invites us to explore it endlessly.

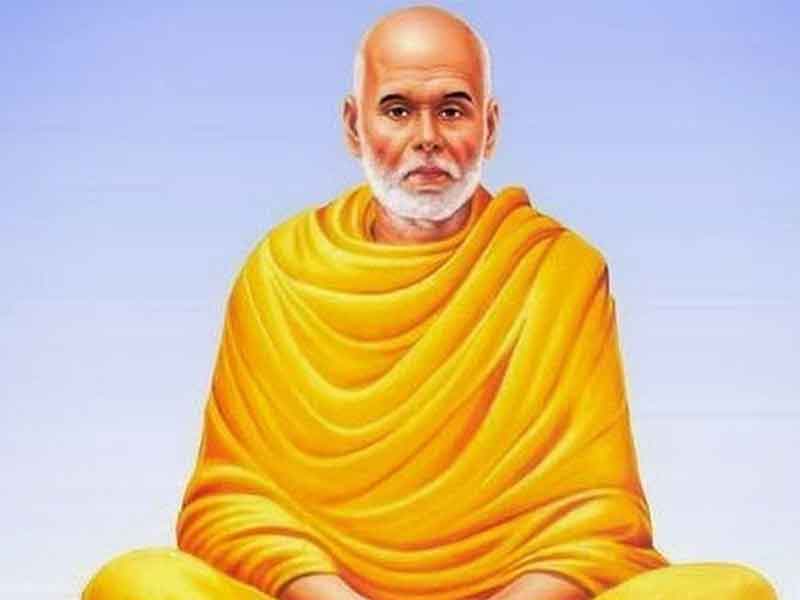

And now, as I walk this path, I do not walk alone. The voices of those who have walked before me — Rumi, Hafiz, Ibn Arabi, and countless others — echo in my heart. Their words are not mere poetry; they are beacons, shining through the fog, reminding me to look beyond the surface and dive deeper into the soul of existence. They remind me that the journey is the point — the constant movement, the unceasing questioning, the quiet surrender to the divine mystery.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

As I leave behind the dogmas and idols of my past, I don’t find emptiness. I find space — space for more love, more understanding, more connection with the divine in all its forms. I find that the universe is far more vast and wondrous than I had ever allowed myself to believe.

I walk forward not with certainty, but with faith — a faith that is alive, that grows, that learns, that questions. I walk forward not with answers, but with a heart open to the beauty of the questions. And in that, I find my liberation.

Subzar Ahmad works as Lecturer urdu in the department of school education Jammu & Kashmir. He can be contacted via email at [email protected]