Introduction

Today in the Art Faculty Lounge of AMU, a celebration of Prof. Irfan Habib, the historian and the teacher was witnessed. The event had been arranged by the Aligarh Society of History and Archaeology (ASHA) under the aegis of Prof. Nadeem Rezavi, who has an enviable record of holding brilliant and engaging academic programs. Tributes poured in for the great historian that is Prof. Irfan Habib. His scholars and students, themselves accomplished scholars, paid tribute to their master in the most glowing terms with Prof. Farhat Hasan and Prof. Asim Siddiqui stealing the show alongside the vivid introduction by Prof. Nadeem Rezavi. Notes author Rana Safavi, Prof. Ruquia Hasan and Prof. Abha Singh were also present and fondly remembered their mentor.

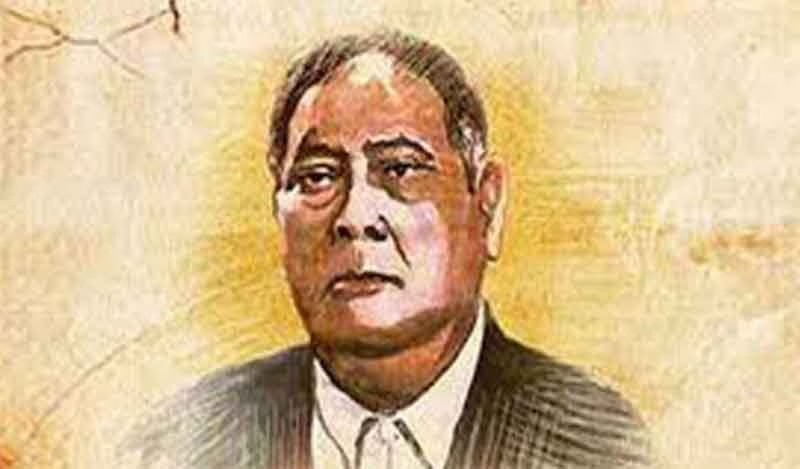

My Encounter With Prof. Irfan Habib

Meanwhile, in the audience another brilliant student of Prof. Habib was present in the form of Prof. Mohammad Sajjad. While my switch to history at the masters level had provoked a curiosity in me to read Prof. Habib, how to engage with his writings was told to me by sir only. During the course of classes on historical methods, I was introduced to Irfan Habib’s writings commencing with his article on Barani’s theory of kingship. Among the myriad of writings on this medieval historian, Irfan Habib stood out for his critique of Barani for denying their agency to the masses in his writing.

Next in line, I discovered his magnum opus, The Agrarian System of Mughal India 1556-1707 (1963) which did two significant things. Of the two, the first which was introducing the study of economic factors and social conditions as instrumental in history and categorising the nature of state as oppressive has been much highlighted but the second has not been adequately talked about. This was setting a firm ground for the introduction of history of technology(it came up in full flow 6 years later through his efforts in the form of various essays). In the introduction of social conditions alongside economic changes and the rise of rebels because of agrarian measures and inexorbitant prices by the kings, he improved upon the thesis of the multifaceted genius of the University, K.M. Ashraf who had written The Life and Conditions of the People of Hindustan 1200-1550 (1959).

Irfan sir’s next book that I encountered was Essays in Indian History: Towards A Marxist Perception (1995). The first two chapters of the book which shall be read together exactly reiterate the point made today by Farhat Sir who stated that Irfan sir’s engagement with Marxism is one where he takes two steps forward and one step back. In his chapters titled Problems of Marxist History and Marx on India, Irfan sir critically engages with Marxist History and states that both oriental despotism and Asiatic mode of production doesn’t hold true for India. However, the most fascinating chapter of the book is his Peasants in Indian history which is a treasure trove of historical information ensconced in brilliant insights where he pulls up references from Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra to highlight the prevalence of forced labour as well as exorbitant tax rates. He acknowledges M.D.N Sahi for the demarcation of three agricultural zones in India during the prehistoric period. The oppressive taxation leading to the peasants being up in arms and sometimes having an agency of their own is made clear by examples from the early medieval period with the most prominent example being that of the Kaivartas revolting against the Pala king of Bengal. In this sense he has basically put his thesis into context through this chapter and categorically characterized the state as oppressive. His chapter Potentialities of Capitalist Development provides us with a valuable conclusion that though in both agricultural and non-agriculturalist production, production for the market formed a very large sector. Merchant capital had developed considerably and had brought artisans under control through forms of the putting-out system and amassing of commodities was also there. Thus, three of the four requirements for capitalist development were present in Mughal India however, owing only to production for the local market and lack of development of shipping technology which could have brought international markets in play were not present. Despite this, the structure of the Mughal Indian economy weathered the effects of the worldwide price revolution without much difficulty. The last chapter which is titled Studying a Colonial- Without Perceiving Colonialism is an eye opener and adds significantly to the economic debate of the 19th century in India. I would go a step further to argue that if we keep in mind the perception of colonialism in other areas apart from economics as well, we would understand the actions of the British much more clearly. Extending Irfan sir’s argument in the political field we would get to know why the British backed the Rajputs and not the Jats in Aligarh region during the 1857 uprising.

The next books of his that I encountered were his set of books on the National Movement(the first volume published in 2017 and the second in 2019) in his People’s History of India series(numbered 30 and 31). The clarity that they provide in terms of the concepts and the insights offered are of great help to every student of history. Separate electorates and the damages it wrought on India have been captured aptly in pages 82-85 in the second volume on the National Movement. Similarly his distinction of communalism and secularism where he tells us how Radhakrishnan’s interpretation of secularism changed the course of secularism as it is practiced in India has been summarised in pages 155-157. In continuation, I stumbled upon his small but very significant booklet The National Movement: Studies in Ideology and History(2011) where he praises the national movement and presents an appraisal of Gandhi’s and Nehru’s leadership of the national movement, in the process distinguishing himself from Marxists like RP Dutt and others who have criticised the National Movement as a movement full of compromises by the elites.

Among his edited volumes, Religion in Indian History (2007), A Shared Heritage:The Growth of Civilization in India and Iran (2002), Medieval India 1: Researches in The History of India 1200-1750 (1992)and Akbar and His India (1987) are the most phenomenal both in terms of remarkable introductions(except in Akbar and His India) and chapter contributions from Irfan Habib himself as well as providing spaces to new historical researches by scholars like Nadeem Rezavi, Abha Singh, Ishrat Alam as well as Najaf Haider. It speaks of volumes of Irfan sir’s erudition that Catherine B. Aisher had this to say in her review of Irfan Habib edited Akbar and His India, “This volume is rich as an in-depth study of cultural and political developments under this extraordinary emperor. Had Habib strung together these loose pearls with an overarching introductory essay, the book would have greater value for the scholar

and beginning student alike.”(The Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 58, Issue 1, February 1999, p.235)

Also of prime importance is Irfan Habib edited On Socialism:Selections From Writings of Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, V.I.Lenin, J.V.Stalin, Mao Zedong (2009) which helps grasp the rise of socialism as an anti-thesis to capitalism. He wrote that the most influential of the Marxist studies was a small book published by Lenin in 1917, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Despite many similarities, there are differences between Hobson’s and Lenin’s frameworks of analysis and also between their respective conclusions. While Hobson saw the new imperialism serving the interests of certain capitalist groups, he believed that imperialism could be eliminated by social reforms while maintaining the capitalist system. This would require restricting the profits of those classes whose interests were closely tied to imperialism and attaining a more equitable distribution of income so that consumers would be able to buy up a nation’s production. Lenin, on the other hand, saw imperialism as being so closely integrated with the structure and normal functioning of an advanced capitalism that he believed that only the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism, with the substitution of Socialism, would rid the world of imperialism. Lenin placed the issues of imperialism in a context broader than the interests of a special sector of the capitalist class. Schumpeter accepted some of the components of the Marxist thesis, and to a certain extent he followed the Marxist tradition of looking for the influence of class forces and class interests as major levers of social change. Therefore he used the tools of Marxist thought to refute the claims of Marxist theory. Schumpeter concluded that there are three generic characteristics of imperialism- 1-At root is a persistent tendency to war and conquest, often producing nonrational expansions that have no sound utilitarian aim, 2- These urges evolved from critical experiences when peoples and classes formed into warriors to avoid extinction. The warrior mentality and the interests of warrior classes remain intact and influence events even after the need for wars and conquests disappears, 3-The drift to war and conquest is sustained and conditioned by the domestic interests of ruling classes under the leadership of those individuals who have most to gain economically and socially from war. However, Schumpeter believed, imperialism would have been swept away into the dustbin of history as the capitalist society matured because capitalism in its purest form is antithetical to imperialism since it is argued that it thrives best with peace and free trade. However, despite the innate peaceful nature of capitalism interest groups that benefit from aggressive foreign conquests do emerge. Under monopoly capitalism the fusion of big banks and cartels creates a powerful and influential social group that pressures for exclusive control in colonies and protectorates, for the sake of higher profits.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

While his academic contributions are immense, I would always respect him for his continuous fight against communalism from all quarters. While he staunchly stood by facts and evidences during the entire Ayodhya issue, he was also the one who had welcomed the Supreme Court’s verdict on Shah Bano case (23rd April 1985) and began collection of signatures in favour of the judgement. Unfortunately, only very few signatures, countable on hands, were in favour of Prof. Habib in general and Shah Bano in particular. This quality to have a spine and use one’s voice as a tone of defiance to the wrong is something Prof. Habib has done consistently.

Hope he lives long.

Bhavuk is a PhD candidate at the Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University. He has been awarded the UGC-NET JRF scholarship and is currently working on the Partition of India with special focus on Uttar Pradesh. He has been a regular contributor to Mainstream Weekly, Countercurrents.org and Rediff.com and Sabrang India and has a research paper published in the reputed Hindi journal Samyantar.