In Pakistan today, identity is not merely personal—it is political, bureaucratic, and frequently perilous. As the country reels from economic distress, intensifying political contestation, and social unrest, the question of who belongs—and who does not—has taken center stage. The media, far from being a passive observer in this process, plays a central role in constructing and contesting the boundaries of national identity.

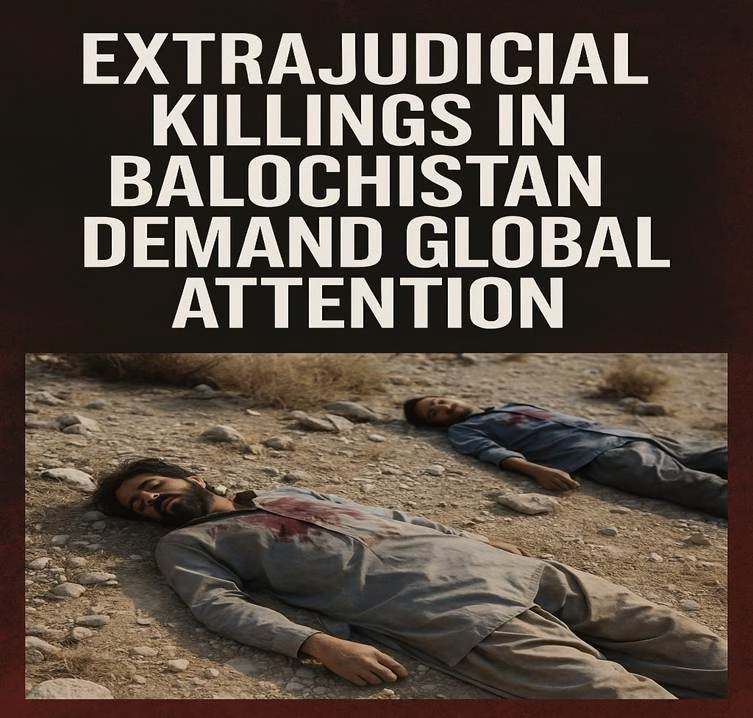

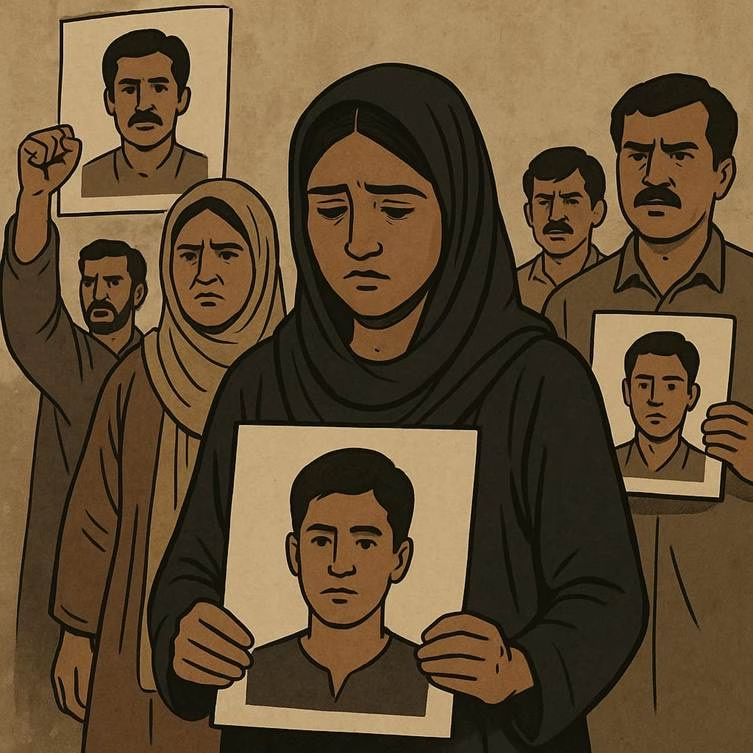

The divergence in media narratives across linguistic and ideological lines is stark. In late 2023, the Baloch Long March saw hundreds of protestors, many of them women and children, walk from Turbat to Islamabad to demand justice for missing persons. English-language newspapers such as Dawn and The Express Tribune documented the state’s heavy-handed response: baton charges, arrests, and attempts to block the marchers from reaching the capital. Yet much of the mainstream Urdu press either ignored the march or framed it as a “foreign-funded” attempt to destabilize the country.

This disparity is neither incidental nor surprising. Urdu-language media, with its wider reach among middle- and lower-income Pakistanis, is often more susceptible to state pressure, ideological policing, and editorial capture. English-language publications, by contrast, have more space to offer critique, but their influence remains confined largely to urban elites, policy circles, and international observers.

Similar dynamics are at play in the coverage of Afghan refugees. In October 2023, Pakistan announced a sweeping plan to expel all undocumented Afghans, triggering international condemnation. Editorials in English dailies criticized the policy as inhumane and diplomatically damaging. But on television and in much of the Urdu-language press, the state’s narrative dominated: refugees were portrayed as security threats, economic burdens, or remnants of a bygone jihadist era.

The securitization of identity in Pakistan has deep roots. It has been shaped over decades by the military’s institutional interests, the legacies of the Afghan war, and an official nationalism that defines loyalty in religious and ideological terms. Yet the consequences of this framing are not abstract. For Afghan refugees, it means statelessness and fear. For Baloch protestors, it means marginalization and surveillance. For religious minorities such as the Ahmadis, it means near-total erasure.

The Ahmadiyya community, constitutionally declared non-Muslim in 1974, is among the most systematically excluded groups in Pakistan. Attacks on Ahmadi homes, businesses, and cemeteries occur with disturbing regularity. Yet these incidents are rarely covered by the mainstream press—especially not in Urdu—due to legal constraints and fear of public backlash. The absence of their stories from public discourse is one of the clearest expressions of Pakistan’s fractured media landscape.

At the heart of these fractures lies a persistent tension: between journalism’s civic role and its entanglement with power. Since the ouster of former Prime Minister Imran Khan, media repression has intensified. Journalists have been arrested, programs taken off air, and digital platforms throttled or banned. The line between national security and censorship has blurred further. For many in the press, self-censorship is not just a professional dilemma—it is a survival strategy.

Yet despite the constraints, critical voices persist. Independent digital platforms such as Naya Daur, Samaaj, and individual YouTube journalists are pushing back against the dominant narrative. Their coverage is often focused on stories that the mainstream neglects: land grabs in Sindh, gender-based violence in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, or forced conversions in South Punjab. These outlets are experimenting with new formats and building loyal followings, even as they navigate financial instability and state scrutiny.

The power of these alternative platforms lies not only in the stories they tell, but in the way they tell them—often through testimony, direct speech, and affective appeals. In doing so, they build what media theorists call “affective publics”: networks of emotional resonance that challenge official narratives and create space for alternative visions of citizenship. But without broader structural change—legal protections, financial independence, and editorial autonomy—their reach will remain limited.

The future of Pakistan’s media landscape hinges on more than just the fight for press freedom; it is about the fight for a more inclusive and equitable national narrative. As the media continues to shape the contours of who belongs and who does not, it faces an existential challenge: to uphold its role as the fourth estate or to capitulate to the pressures of state power and ideological conformity. For marginalized communities—whether Baloch, Afghan refugees, religious minorities, or those critical of the status quo—the media’s power to amplify their voices can either reinforce their exclusion or foster a broader sense of belonging.

As Pakistan’s political landscape becomes more polarized, the stakes in the media’s role in shaping national identity grow higher. The challenge is not only to expose the silences and omissions that have long marked the national discourse but to create spaces where dissent and diversity are not just tolerated but embraced. Independent, alternative platforms have shown that even in the face of severe constraints, critical journalism can still find a way to thrive. But for such efforts to have lasting impact, they need structural support—legal protections, financial independence, and editorial autonomy.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ultimately, the question is not just about what the media reports, but how it reports, who gets to tell their story, and which stories are silenced. In this ongoing battle for narrative control, the resilience of journalists, civil society, and the public’s demand for truth will determine whether Pakistan can move toward a future where its media, and by extension its national identity, reflects a truly pluralistic society. The courage to confront the powers that be and to amplify the unheard voices may be the key to redefining what it means to belong in Pakistan.

Ashish Singh has finished his Ph.D. coursework in political science from the NRU-HSE, Moscow, Russia. He has previously studied at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway; and TISS, Mumbai.