Last spring, encampments filled campuses, protesting the ongoing genocide in Gaza and university complicity. Now people are in the streets protesting the elimination of jobs and opposing deportations. Others have been fighting climate change. The summer of 2020 saw millions in the streets of the U.S. and many other places protesting the torture/murder of George Floyd and the police killing of Breonna Taylor.

Repression has caused many to pull back in fear. However, this essay is about other reasons people quit.

Practical movements against injustice are hamstrung by the sense that communist experiments have failed. People know something is wrong but are unclear what to put in its place. They see that capitalism creates horrors but lack reasonable hope of an alternative.

Much of the problem is on the “left.” Many who call themselves Marxists or anarchists share the unqualified negative view of the great revolutions in Russia and China because those revolutions did not progress toward communism. Others on the “left” are uncritical of the writings of Marx or Lenin or Mao; their appeal is bound to be limited because people look at what earlier revolutions have led to: why do you expect a different result?

What’s missing is Critical Communism. By Critical Communism I mean a communism that is committed to “the forcible overthrow of all existing conditions” and has confidence in a worldwide future of communism, a world without money, where our natural tendency to act helpfully and constructively becomes the basis of human society, where we flourish by enabling one another to flourish, where we work, not for a wage, but to serve one another’s needs.

It is possible to have confidence in that future if we can study earlier revolutions to learn from what they did right—what brought communism closer—and what they did wrong, what undermined organization and motivations needed to bring about a communist world. That is Critical Communism.

To illustrate Critical Communism it is helpful to examine how revolutionaries proposed to get from capitalism to a communist world.

In the Critique of the Gotha Program Marx wrote that after workers seize power they must introduce a wage-like system of individual entitlement to consumer goods corresponding to their contribution to production (like piece-rate wages, which the Soviets used). Early communism was based on “bourgeois right,” necessarily so because the new society “is still stamped with the birth-marks of the old.” Because some can work harder, longer, and more efficiently than others, the equal right is a right to inequality. Marx thought that these defects were “inevitable in the first phase of communist society” because “right can never rise above the economic structure of society and its cultural development.” Therefore, only “in a more advanced phase of communist society” where the division of manual from mental labor has been abolished, where labor is more productive and has become a vital need, where people have changed, only then can we work by the principle from each according to ability, to each according to need.

Both the Soviet Union and revolutionary China followed this formula for the early phase of communism. Capitalism was restored in both.

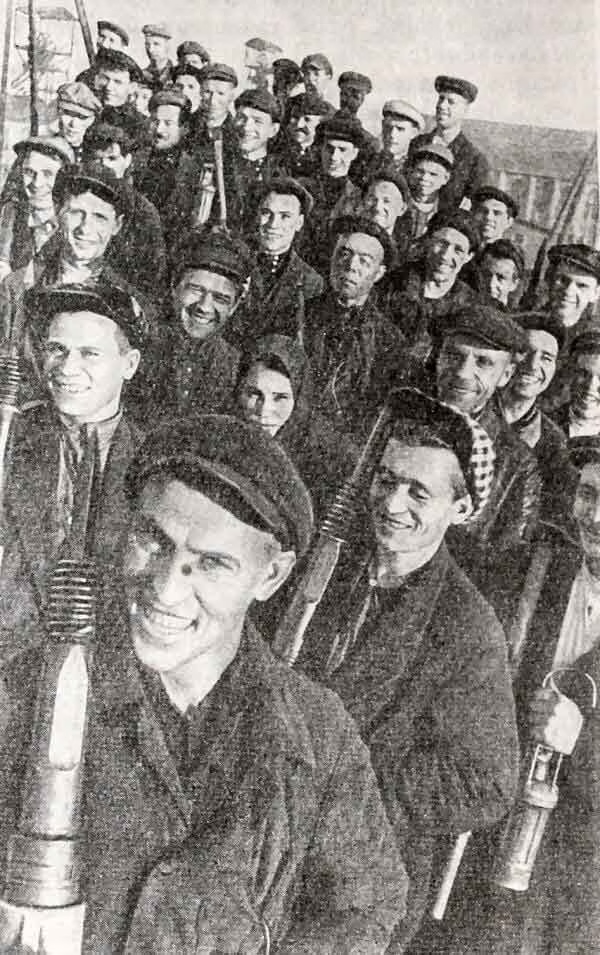

Still, there were fully communist elements in both societies. In the Soviet Union subbotniks gave extra labor for no additional pay, and Stakhanovite workers developed new productive processes. However, these were overwhelmed by privileges for foreign experts and for communist party and government officials whose labor was considered a greater contribution meriting greater reward.

Similarly in China communes equalized access to food for many rural workers; in China there was a saying that whenever there was a difficult task, the communist party members go first; whenever there was not enough of something to go around, the communist party members would take this the last. These communist elements were overwhelmed by higher pay for communist officials and government cadre, with a similar justification to the Soviet’s.

Marx was wrong about the transition to full communism. Here is a speculation more plausible than Marx’s: In early communism, distribution is according to need, not labor contribution. The things we need can only be produced by labor. Communists will work hard out of a commitment to make communism work but receiving no greater material reward. Others will work less hard or not at all depending on how committed they are to make communism work. The principle that describes this is “From each according to commitment.”

But things will change. The communists who work hard without receiving anything extra for their work will draw admiration and respect from others because of their commitment to the collective. Communists will flourish under this social support. Seeing that commitment to the collective leads to the best human life and to support and respect from others, others will be drawn to a communist life. As our commitment becomes more equal, the principle that describes communist society becomes “From each according to ability.” At this later stage of communist society we will differ from one another more in what we are able to do than in our commitment.

The principles “From each according to commitment” and “From each according to ability” describe different phases in the development toward communism.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

This discussion illustrates a method. In their revolutionary stages the Soviet Union and China harbored contradictory—bourgeois and communist—elements. To some extent this is inevitable in any revolution that aims at taking us from capitalism to communism. However, retaining bourgeois right, a wage system, and privileges for some so strengthened the capitalist side of the contradiction that progress toward communism was halted and reversed. We can learn by studying these revolutions, identifying the bourgeois practices that communists retained, and building a movement on more resolutely communist principles. Such a Critical Communist approach can give us reasonable hope of communism and inspire today’s activists that there is an alternative to capitalism that can work.

You can also find two other efforts, examining the Soviet and Chinese revolutions here and here.

Paul Gomberg retired from teaching at Chicago State University as Professor of Philosophy in 2014 and is currently Research Associate in the Department of Philosophy at the University of California at Davis. He is author of How to Make Opportunity Equal: Race and Contributive Justice (Blackwell 2007) and Anti-Racism as Communism (Bloomsbury 2024). He has been a communist activist for more than fifty years.

Photo: Stakhanovite miners. Photograph from 1935. available at: https://www.history-at-russia.ru/xx-vek/dvizhenie-peredovikov-proizvodstva.html.

Originally published in Marxist Sociology