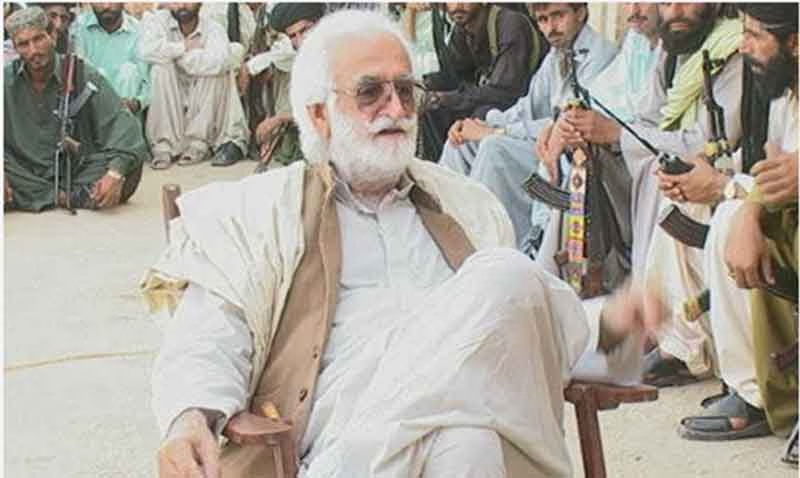

In the arid mountains of Balochistan, long after the missile strike, the state-sanctioned silence, and the deliberate erasure, one name continues to resonate—Nawab Akbar Shahbaz Khan Bugti. To those who rule Pakistan, he was a rebel who needed to be extinguished. To those who inhabit the neglected corners of its federation, he remains a voice of unyielding dignity, a symbol of resistance carved into the stones of the Baloch homeland.

Born in 1927 in Barkhan, educated at Aitchison College and Oxford, Bugti’s journey from tribal chieftain to federal minister to fugitive was not simply personal—it was the story of a nation within a nation, perpetually deceived and dispossessed. He served Pakistan as Interior Minister, Governor, and Chief Minister of Balochistan, yet no title he ever held could insulate him from the realization that Balochistan was not seen as a partner in the federation, but as a quarry to be extracted and pacified.

Bugti was no romantic revolutionary. For much of his life, he believed in negotiation, federalism, and the possibility of equitable coexistence. But that belief corroded with every broken promise, every military outpost built where schools should have stood, every deal struck in Islamabad without a thought for those who lived on the land. Balochistan gave Pakistan its gas, its minerals, its ports—yet received nothing but surveillance, suspicion, and soldiers in return.

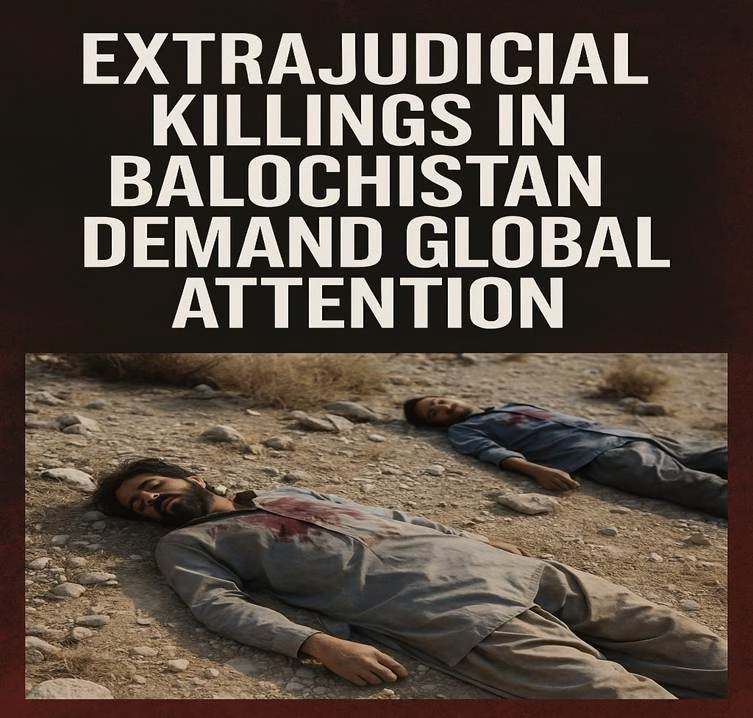

When the Pakistan Army intensified operations in Dera Bugti and Kohlu in the early 2000s, Bugti, then nearly 80, retreated to the hills—not as an act of war, but as a final protest against a state deaf to all else. He was not hiding; he was standing. When missiles struck his mountain hideout on August 26, 2006, they killed his body, but they animated something far more enduring: a collective memory of betrayal, a wounded pride, and a struggle that now had its martyr.

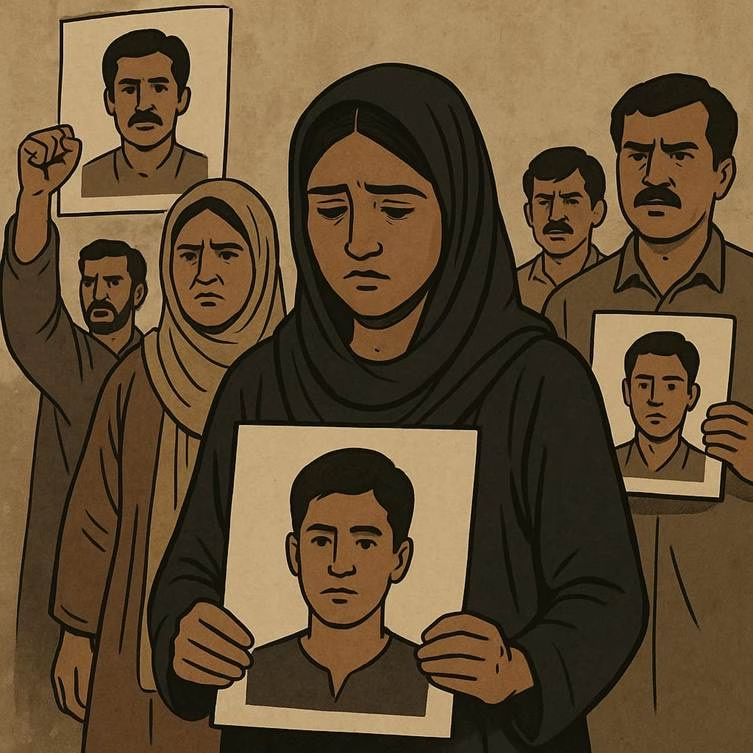

The Pakistani state refused to return his body to his family. There was no funeral. No grave. The absence was meant to humiliate, to erase. But the people of Balochistan did not forget. They do not forget. Bugti’s name today is not one of the past; it lives in whispers, in protests, in the eyes of the young. It moves through the speeches of Dr. Allah Nazar, the defiance of Mahrang Baloch, and the declarations of Mir Yar Baloch. His image is scrawled on walls the state tries to paint over. His voice, long silenced by gunfire, now speaks louder in silence than many do in speeches.

Pakistan continues to deny that Balochistan is bleeding. The army blames foreign conspiracies, accusing India, the CIA, and imagined bogeymen, as if the calls for freedom echoing through the Baloch hills were satellite transmissions rather than the raw cries of the dispossessed. But there is no foreign hand stronger than the weight of history. The insurgency is not imported—it is inherited.

Bugti’s assassination was meant to serve as a warning. Instead, it has become a parable. While Islamabad builds roads to Gwadar and sells Balochistan to Chinese investors as part of its grand geopolitical theater, it has failed to answer a simpler question: what legitimacy remains in a state that does not mourn the people it kills, does not count the ones it disappears, and does not remember the ones it once called its own?

Akbar Bugti was not just a man. He was an idea—a belief that Balochistan was not a prize to be won, but a homeland to be respected. His death was not the end of his rebellion, but the beginning of its transformation. Today, in every mother waiting for a disappeared son, in every student protesting abduction, in every tribe resisting military incursion, Bugti lives.

His grave remains unmarked. His memory does not. In the archives of Pakistan’s conscience, if such a place still exists, Bugti is the page that keeps tearing itself free from censorship. He is not a ghost. He is the mirror the state dares not look into.

And as long as there are people who refuse to forget, Akbar Bugti will remain alive—where tyranny fears memory the most.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ashish Singh has finished his Ph.D. coursework in political science from the NRU-HSE, Moscow, Russia. He has previously studied at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway; and TISS, Mumbai.