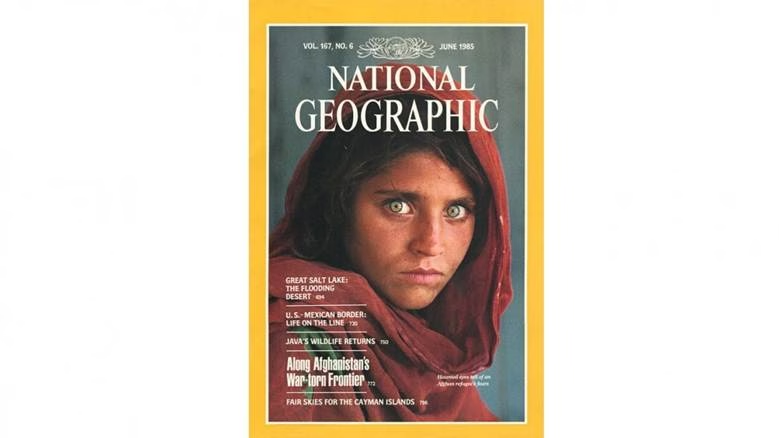

With my sudden craving for freshly fried Jilapi, I ended up going to the Niralla Sweets (a Pakistani joint) where they make it every day. As the cashier was ringing up the sale, I looked around the dimly lit place. I was surprised to see 12-year-old Sharbat Gula’s National Geographic magazine’s June 1985 cover photo was featured on the wall. The photo was taken by Steve McCurry in ’84 at Nasir Bagh refugee camp in Peshawar, Pakistan. Though it has been 40 years, some of you might recall Sharbat Gula with a piercing green-eyed stare. She was otherwise known as the “Afghan girl.” Because of her ubiquity due to massive international media coverage, Sharbat Gula became the face of the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan. Once dubbed the “Mona Lisa of photojournalism,” Gula along with her family was evacuated to Italy after Afghanistan fell to the Taliban in 2021.

Sharbat Gula’s picture had a “game changing” effect on those who saw it. McCurry was able to capture the horror of a war and its impact on a young refugee child with a single shot. Her fear and anger for having to live in a refugee camp wearing a shabby ethnic dress, and her head covered with a torn red dupatta thus became the emblem of Afghan-Soviet war. The look of horror in those green eyes spoke as a testament to that displacement.

When McCurry showed up with his camera, Sharbat Gula decided to hide behind the campsite as Afghan women are not allowed to be photographed with an open face. However, McCurry found her and took that iconic shot that made both of them famous. When Gula was photographed, McCurry did not know her name.

He learned her name 17 years later in 2002 when he went to find her. At the time, she was illegally living in a border town between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Prior to that, she was displaced a few more times and was considered stateless in Pakistan. Since the Soviet occupation, Sharbat Gula has had to suffer immense hardship. In 2016, Gula had made headlines in Pakistani media on charges of document forgery to receive government assistance. It is a common practice among the Afghans living in Pakistan.

We have heard stories about her plight in Pakistan’s refugee camp before. She was forced into an early marriage at 13 with an older man. She was barely a teenager when she got married and ended up having five children.

It was reported that for a few weeks, Sharbat Gula’s face constantly flashed on television screens across Pakistan to humiliate her as she was an illegal occupant. The Pakistani government decided to expel her to Afghanistan. Gula was particularly singled out as she was the famed “Afghan girl.” Sharbat Gula was arrested.

When one is stateless, without any identity papers, and has five mouths to feed, and no sustainable income, what choice is there but to resort to scams? As compensation, she had received some money from National Geographic after the publication of the issue. But that money was not enough to be sustained long-term.

Hearing about her trouble, then Afghan president Ashraf Gani welcomed her back to Kabul. She was given assurance of financial support and was offered a government-funded apartment. She settled in with her husband and four children. One daughter died while in Pakistan because of lack of treatment when she was sick.

The family was happy to be back in Afghanistan. Things were looking up. The children started going to school. Then her husband passed away. When the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan, Sharbat Gula and her 4 children were whisked away to Italy by a nonprofit aid agency. The Italian Prime Minister’s office was involved in the evacuation process.

As a result, the context of her struggle has changed. Gula ending up in Italy is indeed a bitter-sweet story.

The obvious question is why was she taken to Italy of all places? The thought of belonging to a country, any country, must have been very appealing to Sharbat Gula as she needed to get out of Afghanistan before the Taliban could track her. It is not easy being in Italy without knowing the language. The Italians refuse to speak in English or any other language. Italian is not extremely hard to learn for an English speaker as its grammar is not complex. Sharbat Gula is illiterate.

She was not given choices of countries and places to pick from. Nor was she in a position to have weighed all the pros and cons before repatriation. Gula is a single mother with four children to support, and they had to leave Kabul in a hurry. One married daughter also lives with her.

Upon arrival, Gula said she had heard Italy is a nice place and the people are friendly. That gave her comfort in thinking that it was going to be her next home. As a stateless person, she was used to living in a vacuum. Until her move to Italy, she has been in a perpetual loop to advocate for her own rights. Without a state one cannot do that. What rights transcend ‘statehood’ – is not known to refugees like Gula.

Sharbat Gula, “Whose eyes captured the world, sees a new life and finds a new voice in Italy,” is the title of an expose on her in La Repubblica, a daily general interest newspaper in Italy. How is Sharbat Gula doing in Italy?

It is hard to tell from the photo of the news story. In a barely furnished apartment, sitting on a sofa, Gula was pictured in her traditional attire without the burqa and niqaab. She looks forlorn and somewhat sad — it is not easy to guess what is behind her gaze. At 53, her youth is gone – but those green eyes still sparkle a little.

Gula initially refused to be interviewed by the media. She preferred to remain anonymous without drawing any attention to her and the children. She feared if recognized, she might face difficulties. In the past, she used to have nightmares about being photographed for National Geographic. Besides, the humiliation and shame she had to face in Pakistan was still very fresh in her mind. For her children’s sake, she wanted to live a peaceful life in relative safety – away from public scrutiny.

Few months later, she changed her mind and gave an exclusive interview. The story gave a positive twist to Gula and her family living there. However, she did not allow her children to be pictured. As narrated in the story, the middle daughter has been picking up Italian in school and is the interpreter in the family. Gula is encouraging her to study hard and make something of herself. She doesn’t want her daughter to end up like her – uneducated, homeless, poor, and shuttling between countries.

As common in a mother across cultures, she hopes her daughter becomes a doctor. If her dreams come true, only then she will return to Afghanistan — she confided to the interviewer.

The rest of the family, including Sharbat is learning Italian as well. She gets a one on one lesson from a private tutor, and the two women have forged a bond according to the article. Sometimes they have to use sign language to communicate.

It also states that “this isn’t just a language lesson; it’s the rebirth of a woman who, after so many years in silence, is finding a new voice. And a new life.”

“I feel happy”, Gula confirms, “Since I started studying I feel like a little girl who is just starting to learn.”

Years have gone by through the travails and hardships of life. Sharbat is no longer a refugee; she now is a migrant in Italy. We can review her life in the context of hardship, resilience, and hope.

This sentiment can be illustrated in the words of Political Science professor emeritus Ahrar Ahamd. In an essay titled “Home and Displacement,” he writes: “This self-conscious decision does not imply a forsaking of one’s historical baggage of family bonds, cultural tastes, or individual habits. But, while the “ties that bind” remain in effect, and while the journey of re-settlement and new identities may initially entail some struggles and discomforts, and may even carry elements of anguish, guilt and after-thought, these ties eventually face “erasure” in the context of new demands, expectations and blending imperatives.”

Sharbat Gula is a classic case of displacement – she has been to one place after another. Because of war and well-founded fear of persecution, she never had a permanent home until her move to Italy. The National Geographic photo made her a well-known person because of massive international media coverage. At first, she was used as a symbol of Soviet invasion. Secondly, she got attention as she had to flee once again Taliban occupied Afghanistan.

The emotion of displaced people resonates furthermore in words of Professor Ahmad: “While the reality of people travelling, moving, discovering, settling and building new homes and identities is quite old, this forced dispersal of entire groups of people across borders through war, persecution, exclusion, threat, or targeted violence, is a relatively new phenomenon.”

According to UNHCR, around 40 percent of the world’s population who are forcibly displaced are children. During the Soviet incursion, thousands of Sharbat Gulas were displaced from their native Afghanistan. They had no choice but to leave their habitual residences in their homeland as they were facing persecution due to the conflict.

People usually think that children are spirited but when they are uprooted and enforced to live in a camp with others, they also bear the brunt. They become indignant, and their feelings are usually overlooked. Children often cannot really verbalise their emotions. Living in a refugee camp denies them access to adequate food, clean water, health care, and sanitation.

Forced displacement is counterproductive on many levels as both children and adults face many types of traumatic events and difficulties. The loss of a protective environment cannot be replaced with anything else. Moreover, the pain of the loss of community, and the place that once was home is suddenly taken away from them. Such a loss is hard to cope with. Children like Sharbat Gula become very susceptible to sudden changes in their life. The enormous uncertainty that children face in a makeshift camp most possibly hampers their psychological development.

Young Sharbat Gula’s fate was similar. She and her family had remained displaced until she went back to Kabul to be displaced again. Gula had gained fame because of the symbolic photo — that fame was also a source of constant torment.

Until Sharbat Gula landed in Italy, her five-decades of life had been a whirlwind of events – often chaotic, unsafe, and intense. Her iconic image on the National Geographic magazine cover had evoked worldwide empathy. People thought they really knew her – and remained obsessed with the visuality of her photo. The photo was cleverly cropped to put emphasis on her headscarf and green eyes. 40 years on, as the entrancing girl navigates through life’s journey, the “Afghan Girl” is still talked about. Because of her emblematic image, she has become part of world culture. The Italian newspaper did not use Sharbat Gula as the past model girl but a visionary who is going forward with a confident mindset.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Zeenat Khan (University of Rhode Island, USA, Holy Cross College, Dhaka) co-taught Gr. 5-8, as a Special Ed teacherto students with mild learning disabilities in Washington DC. She is a contributor to South Asia based journals and magazines.