From its inception in 1947, Pakistan has grappled with the contradictions of building a unified nation-state from deeply diverse parts. While religion was positioned as the glue that could hold the new polity together, this assumption masked profound ethnic, linguistic, and regional differences. The promise of federalism was quickly replaced by a centralized, often authoritarian structure dominated by military and bureaucratic elites — mostly from Punjab. This centralization, justified through the language of national security and Islamic unity, steadily alienated Pakistan’s peripheries.

What followed was not just political unrest but a recurring cycle of rebellion, repression, and resentment. These movements did not emerge in a vacuum; they were deeply rooted in empirical realities — broken political agreements, unfulfilled promises of autonomy, economic extraction, and violent suppression. The demands for secession that have punctuated Pakistan’s history are best understood as a consequence of the state’s persistent failure to build inclusive institutions.

East Pakistan: A Majority Treated as a Colony

East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) was home to the majority of Pakistan’s population at independence. Yet this demographic fact did not translate into political power. The first major fracture appeared in 1948 when Muhammad Ali Jinnah insisted on making Urdu — spoken by a minority — the sole national language. The Bengali Language Movement (Bhasha Andolon), which began in earnest in 1952, saw students killed by police during protests in Dhaka. This was not merely a cultural grievance; it was a harbinger of deeper political disenfranchisement.

In 1970, the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won 160 out of 162 seats in East Pakistan — a clear majority in the 313-member National Assembly. However, the West Pakistani leadership, dominated by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and General Yahya Khan, refused to hand over power. The state responded with Operation Searchlight in March 1971, unleashing mass violence, including rape, massacres, and the displacement of approximately 10 million refugees into India.

According to declassified Indian and U.S. intelligence reports, the death toll ranged from 300,000 to over 1 million. The war ended in Pakistan’s defeat and the creation of Bangladesh in December 1971. This was not secession in the conventional sense; it was the result of a majoritarian region breaking free from a state that had refused to accept its electoral verdict. The very foundation of Pakistan’s ideological unity — religion — crumbled under the weight of political suppression and military violence.

Balochistan: Insurgency as Response to Extraction

Balochistan was incorporated into Pakistan in 1948 through a controversial and contested annexation of the Khanate of Kalat. Despite multiple accords promising autonomy, including the 1948 agreement and the 1973 Constitution, the central government repeatedly failed to honor these commitments.

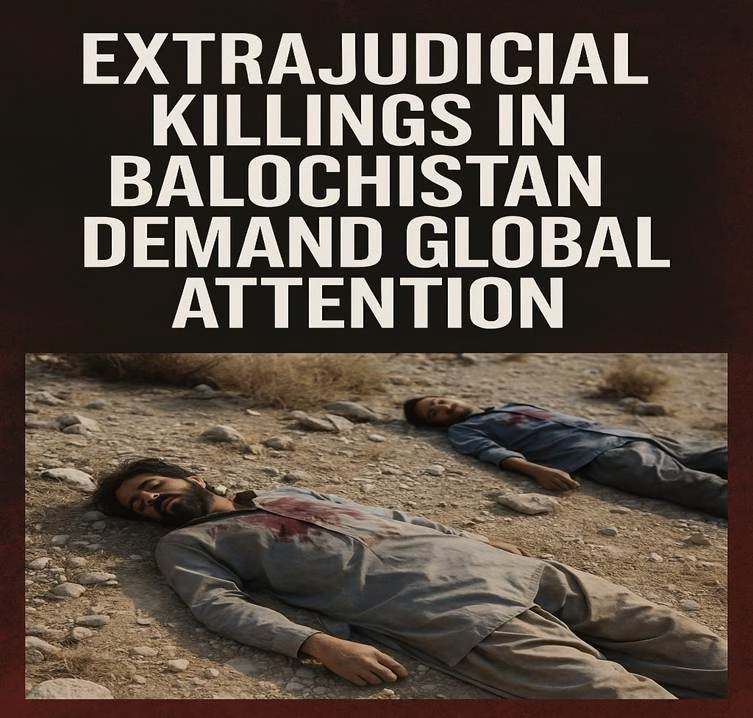

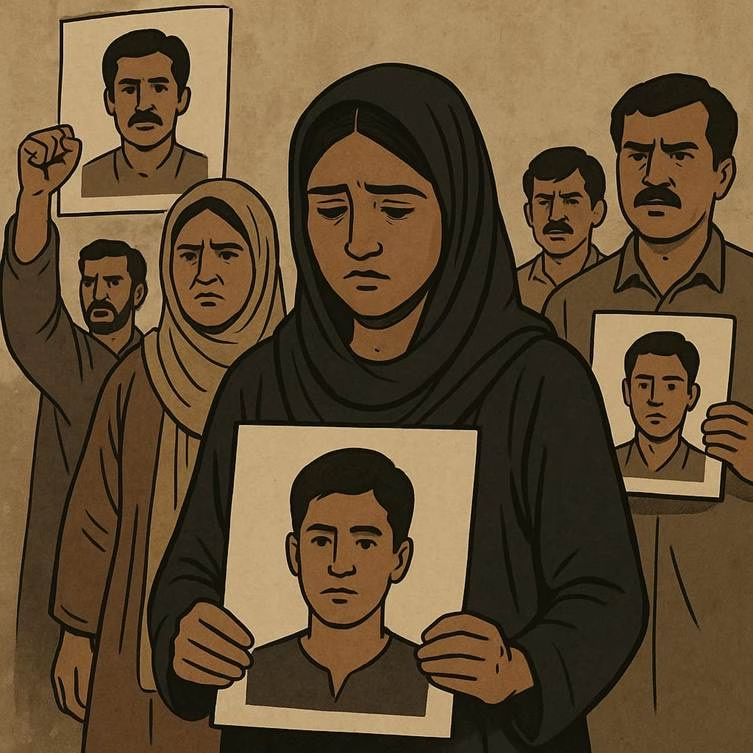

There have been five Baloch insurgencies since 1948 — in 1948, 1958, 1963-69, 1973-77, and the ongoing uprising since 2004. The military’s response has consistently involved large-scale operations, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), over 2,000 Baloch individuals have gone missing in the past two decades alone.

Economic marginalization has fueled the rebellion. Balochistan accounts for 43% of Pakistan’s natural gas production but receives less than 10% of national energy revenues. Projects like the Saindak copper-gold mine and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) have further intensified grievances. While touted as development projects, these ventures are seen locally as extractive enterprises with little benefit to the native population. The state’s repeated militarization of dissent — rather than dialogue or inclusion — has pushed even moderate voices toward separatist narratives.

Sindh and the Mohajir Question: Urban Discontent Weaponized

Sindh’s experience with the Pakistani state has been shaped by two parallel trends: the marginalization of ethnic Sindhis and the political manipulation of Mohajir grievances. After Partition, millions of Urdu-speaking migrants from India (Mohajirs) settled in Karachi and Hyderabad, becoming a new urban elite. While initially favored by the state for their bureaucratic skills and loyalty, tensions grew as indigenous Sindhis demanded greater representation.

The language riots of 1972, sparked by the Sindh Assembly’s bill making Sindhi the official language of the province, exposed deep fractures. The rise of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) in the 1980s was a direct response to the declining power of Mohajirs and their exclusion from provincial politics. MQM quickly became a powerful force in Karachi, but the state’s response — Operation Clean-up in 1992 and later paramilitary crackdowns — relied on extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and ghettoization.

In 2016, HRCP reported over 1,000 MQM workers killed in security operations since 1992. Simultaneously, Sindhi nationalist movements like Jeay Sindh continue to call for “Sindhudesh,” citing economic deprivation and cultural erasure. Though lacking a militant wing, these movements are consistently harassed, with leaders like Shafi Burfat forced into exile. The state’s refusal to negotiate with legitimate provincial actors has ensured that demands for autonomy are viewed through the prism of sedition.

Pashtun Regions: From Buffer Zones to Battlegrounds

Pashtun regions have been treated less as constituents of a nation-state and more as geopolitical tools. During the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989), Pakistan’s military regime turned the tribal areas into recruitment grounds for jihad. Post-2001, these same areas became targets of drone strikes, military operations, and counterterror campaigns.

The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), merged into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2018, remained under colonial-era laws like the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR) until recently. These areas had no representation in regular courts and were ruled through collective punishment doctrines. According to UNDP data, FATA had Pakistan’s lowest human development indicators before the merger.

The emergence of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) in 2018 brought to light systemic abuses: disappearances, minefield injuries, and harassment by the military. Leaders like Manzoor Pashteen have repeatedly called for constitutional rights and an end to the militarization of civilian spaces. While the PTM does not advocate secession, the state’s labeling of its peaceful demands as “anti-national” reveals a deep paranoia about its own peripheries.

Gilgit-Baltistan and Kashmir: Citizens Without a State

Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) and Pakistan-administered Kashmir are territories without constitutional status. While claimed as integral parts of Pakistan, they lack representation in the National Assembly and Senate. GB, despite being the site of massive infrastructure investment under CPEC, remains governed by presidential orders rather than a provincial constitution.

In 2020, the Imran Khan government proposed giving GB provisional provincial status — a move quickly opposed by nationalist groups who saw it as symbolic rather than structural. The people of GB have demanded full citizenship rights, including judicial access and political representation, but have been denied under the guise of the Kashmir dispute.

Security forces have cracked down on activists like Baba Jan, who was sentenced to life imprisonment for leading protests after a deadly landslide in 2010. The state’s strategic interests have consistently trumped human rights or democratic inclusion, turning these regions into administrative colonies governed by Islamabad’s directives, not their own representatives.

Punjab: The Power Core of the Federation

Punjab, home to more than 50% of Pakistan’s population, dominates the armed forces, civil service, and economic policymaking. According to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, over 70% of senior military officers hail from Punjab. Despite being the beneficiary of disproportionate state resources, Punjab is rarely the subject of scrutiny in national discourse.

This imbalance has created a federation where peripheries are governed by a core that claims national identity as its own. When dissent erupts — whether in Balochistan, Sindh, or the tribal areas — it is often dismissed as “foreign-backed” rather than introspected as a failure of governance. The state’s unwillingness to confront this internal asymmetry turns federalism into a fiction.

A Nation in Permanent Crisis

Secessionist demands in Pakistan are not random eruptions — they are patterned outcomes of structural exclusion. When a state consistently refuses to listen, governs through fear, and treats its own citizens as threats, rebellion becomes a rational response. These movements have varied in ideology, scope, and tactics, but they share a common origin: the state’s refusal to accommodate pluralism.

Unless Pakistan reimagines itself as a truly federal, inclusive polity — with equity in representation, rights, and resources — the cycle of discontent will endure. The fracture lines are not hypothetical. They are real, and unless addressed, they threaten to redraw the very map that once promised unity through faith alone.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest CounterCurrents updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Ashish Singh has finished his Ph.D. coursework in political science from the NRU-HSE, Moscow, Russia. He has previously studied at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway; and TISS, Mumbai.